By Anna Willig, Watershed Conservation Research and Data Specialist

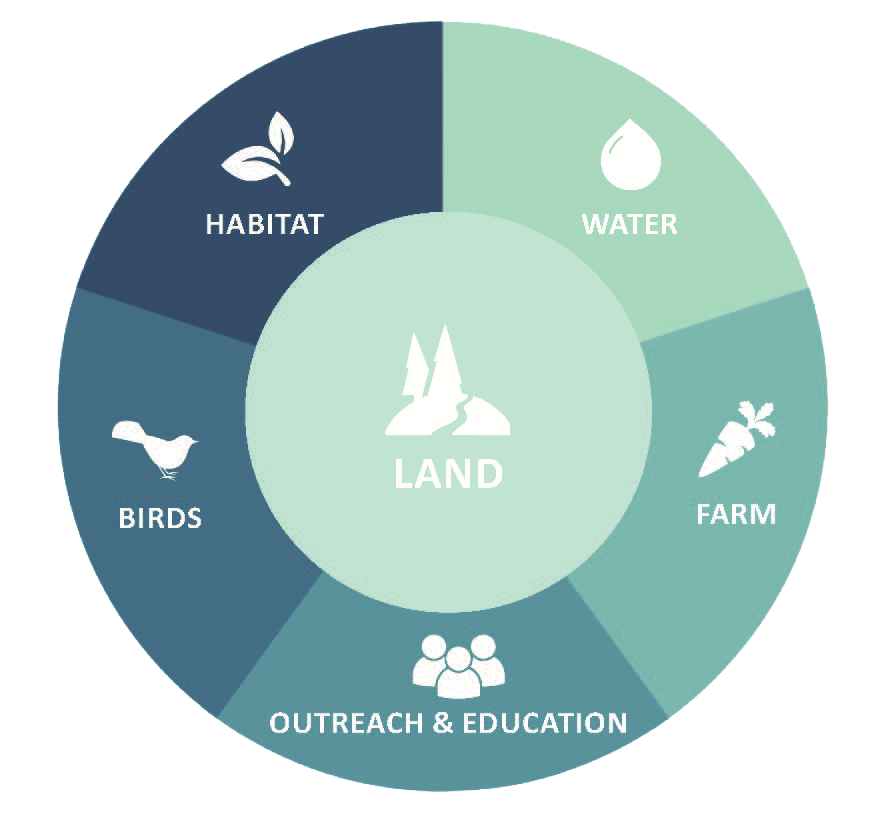

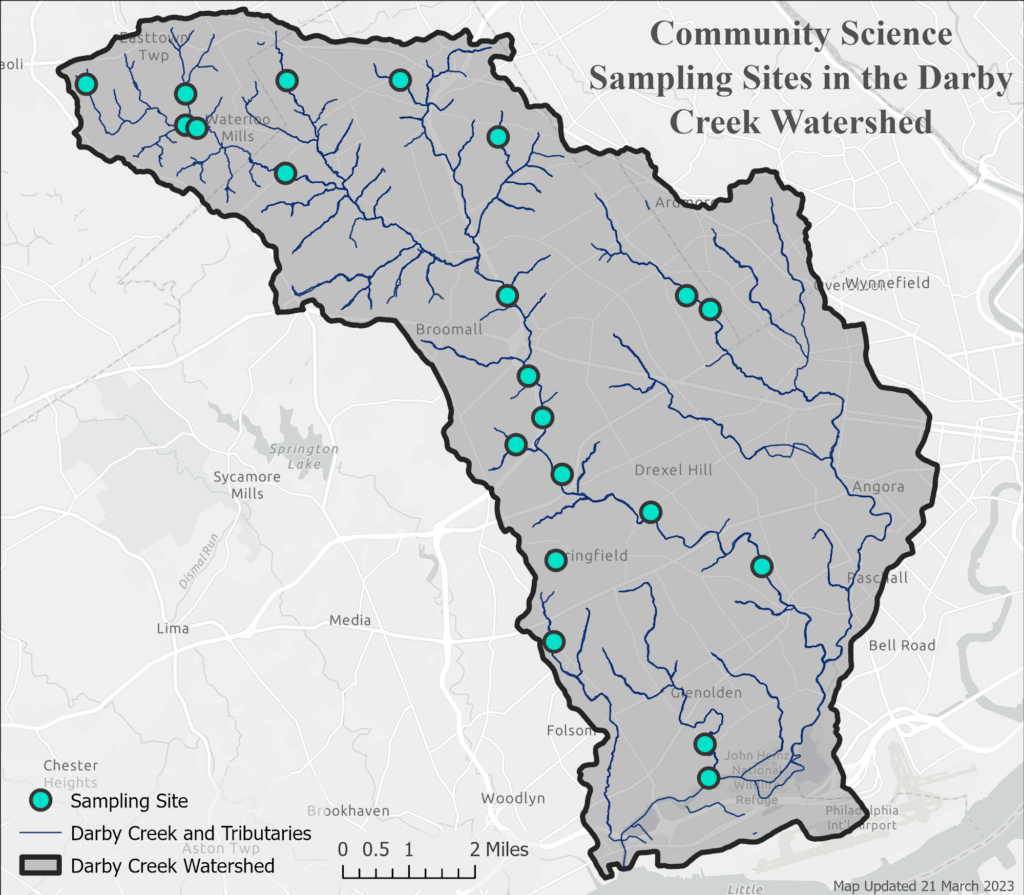

This March, the Darby Creek Community Science Monitoring Program (DCCS) — a collaboration between Willistown Conservation Trust, Darby Creek Valley Association, and Stroud Water Research Center — celebrated its second birthday! We officially launched the DCCS in March 2021 with two stalwart volunteers sampling at two sites in Berwyn. Today, 28 volunteers actively monitor 21 sample sites throughout the watershed, extending past Folcroft (Figure 1). The goals of the DCCS are to learn about the health of Darby Creek and its tributaries and identify key restoration sites through monthly water quality monitoring visits.

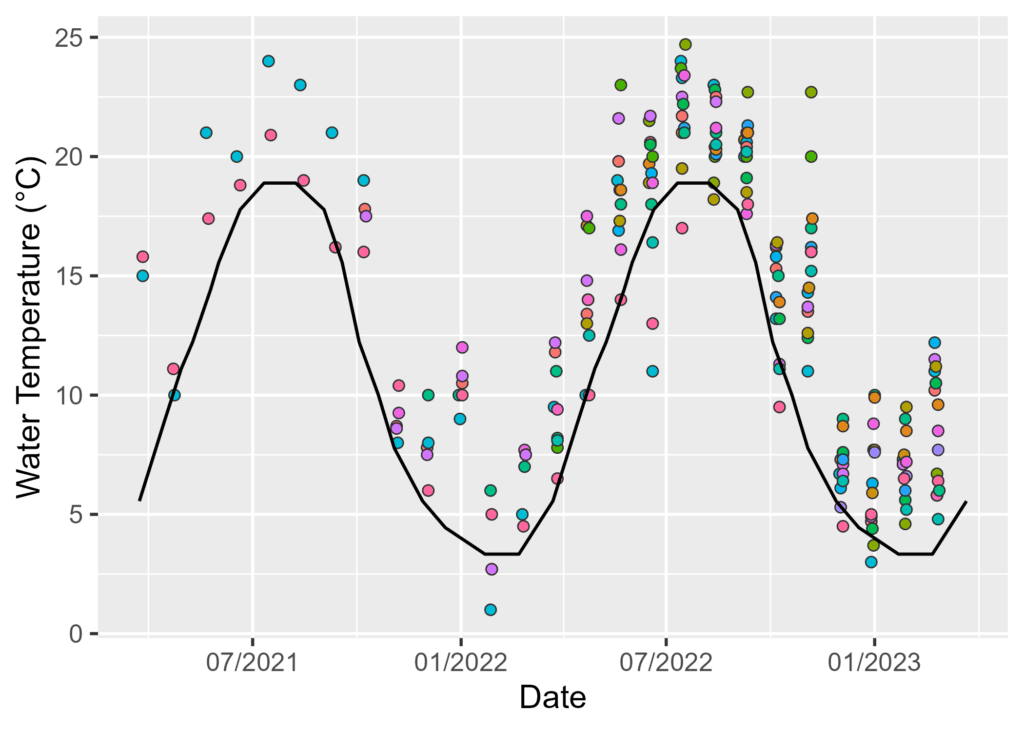

Water temperature is a key indicator of stream health. As water warms, it holds less oxygen and becomes inhospitable to aquatic wildlife. Trout fishes are one of the most sensitive groups to high water temperature and are a benchmark for healthy streams. If streams are too warm for trout, they are likely too warm for a host of other aquatic species, including mussels and macroinvertebrates. Water temperatures in Darby Creek are often too warm to support the reproduction and survival of trout species (Figure 2). The removal of trees along a stream, increases in development, and stormwater runoff can all contribute to warming streams. The best way to cool streams down is by reforesting stream banks, planting native plants, and designing stormwater management that allows rain to soak into the soil.

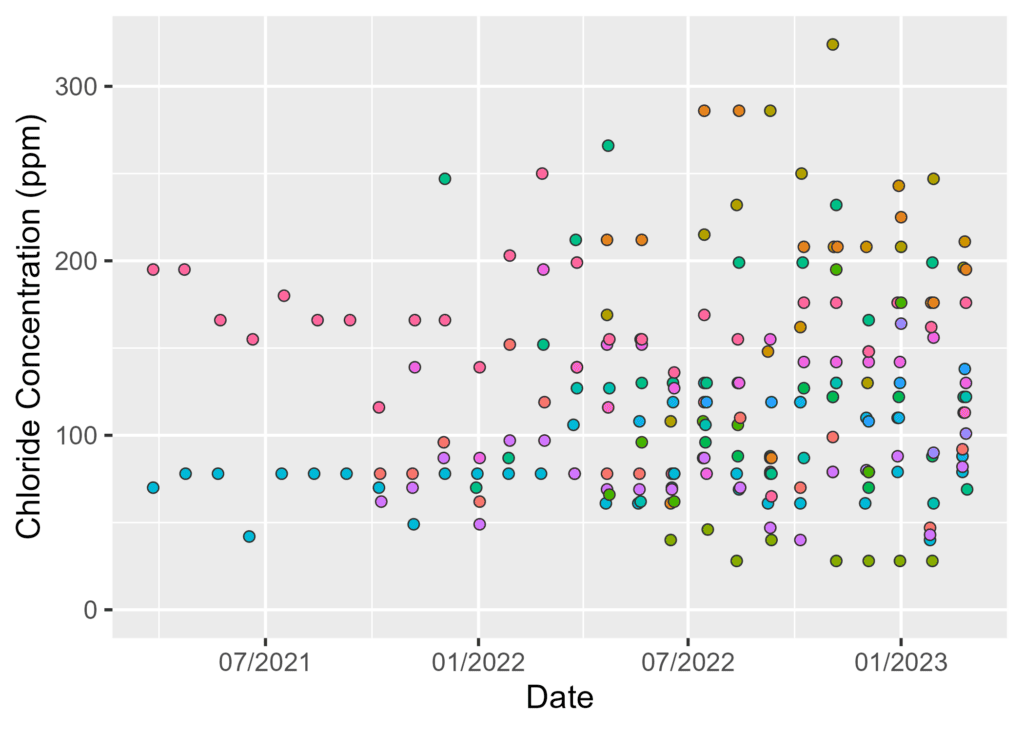

Another indicator of stream health is chloride concentration. Chloride is an ion that reflects the amount of salt in streams. Road salt is the main source of salt in streams and is increasingly recognized as a major pollutant. Chloride concentration varies widely between sites in Darby Creek (Figure 3). Generally, chloride concentrations are below the chronic exposure threshold set by the EPA, but are above levels that researchers have found harmful to aquatic organisms. While road salt is necessary for safe winter travel, limiting use and sweeping salt up after storms can reduce salt pollution in streams.

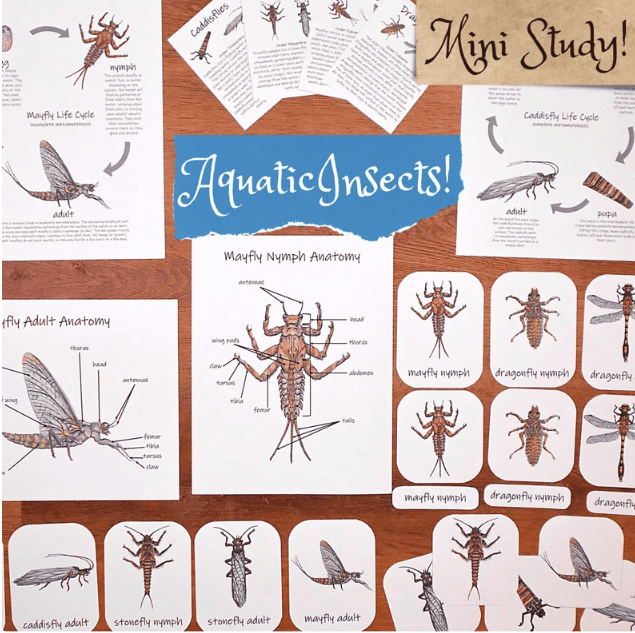

While temperature and chloride concentration reflect a host of threats to the health of Darby Creek, our volunteers have found good news in Darby Creek. One volunteer found a small population of freshwater mussels — which are uncommon in Darby Creek — at one sample site. Freshwater mussels are one of the most imperiled groups globally, and finding them in Darby Creek is a clear indicator that, despite development and pollution, the creek is still a critical resource deserving of protection. We are working with research groups to document and protect this precious group of mussels.

We are incredibly grateful to all the fantastic volunteers who participate in this program. Through their dedication and enthusiasm, the DCCS has exceeded all expectations! The heart of this program is partnership, and we are thankful for support from Stroud Water Research Center and Darby Creek Valley Association. As the DCCS enters its third year, we are excited to build on partnerships, gain new insights, and leverage our volunteers’ data to improve the health of Darby Creek.

To learn more about the Darby Creek Community Science Monitoring Program, please visit their website or email Lauren McGrath (lbm@wctrust.org).