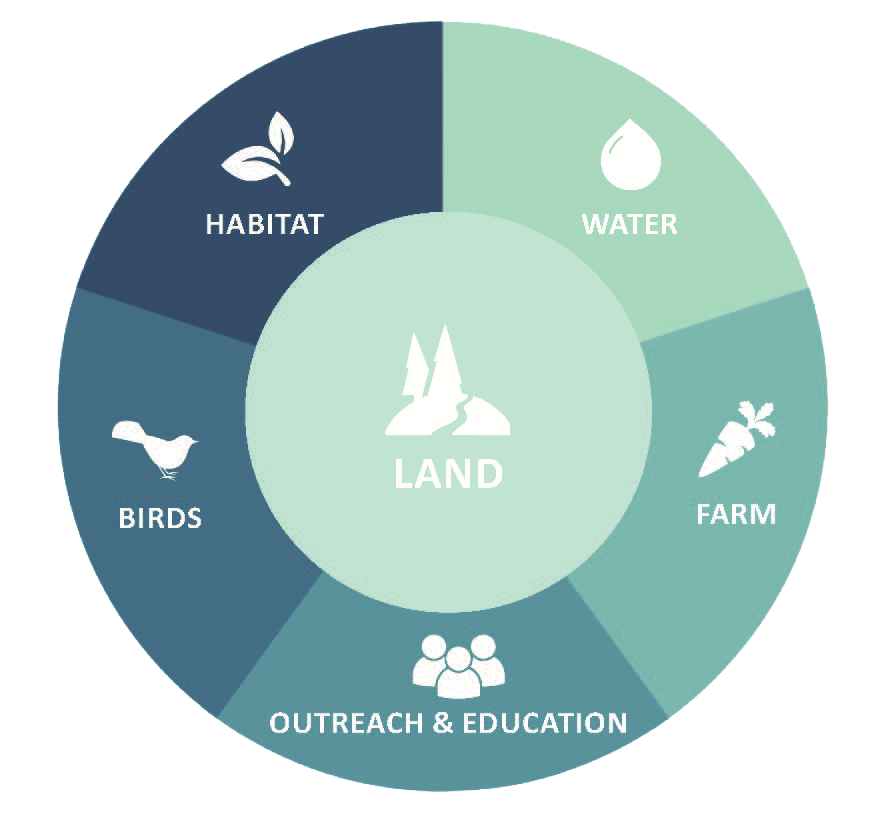

Internships are an integral part of Willistown Conservation Trust’s (WCT) work. Each year, hardworking students join our team and bring with them a wealth of experience and enthusiasm. They provide essential duties during our busy seasons working on the farm, banding birds, maintaining trails, planting trees, taking water samples, mapping, interacting with volunteers, teaching our young Rushton Nature Keepers, and more. These students represent the future of the conservation movement, and we are proud to play a role in educating and inspiring these future leaders!

Get to know our interns below, and be sure to say hi when you see them!

WATERSHED

| Sarah Barker (she/her) Watershed Protection Program Co-Op Sarah is a junior at Drexel University where she is majoring in Biology with a concentration on evolution, ecology, and genomics. Before she joined us, she spent six months working for a water quality start-up called Tern Water as a water chemistry research/lab assistant and another six months working at Polysciences as a quality control chemist. Now, as a Watershed Protection Program Co-op, her responsibilities include assisting in sample collection, equipment maintenance, data collection and entry, running laboratory analyses, and aiding in educational outreach. When she’s not learning about the local ecology and effects of land use on the environment, Sarah enjoys singing, writing, doing arts and crafts, and spending time with her two cats. |

| Sally Ehlers (she/her) Watershed Protection Program Co-Op Originally from Little Silver, New Jersey, Sally Ehlers is an undergraduate student studying Environmental Science, Biology, and Writing at Drexel University. Last spring and summer, she worked as a co-op for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Fisheries lab in Highlands, New Jersey, where she focused on projects that addressed the impacts of toxins on young life stages of marine and estuarine fishes. Here at WCT, she will assist with a variety of data collection including water quality monitoring, monthly sampling, and annual macroinvertebrate sampling. For her independent project, she will be analyzing macroinvertebrate data collected by the Watershed Team. |

RUSHTON FARM

| Maria DiGiovanni (she/her) Conservation Apprentice A recent graduate of Cornell University, Maria DiGiovanni studied International Agriculture and Rural Development, and as a Conservation Apprentice here at Rushton Farm, she is ready to take on the many daily tasks necessary to get food from the farm to our CSA members and greater community. Maria comes to us with all sorts of experience, including studying how niche meat farmers in North Carolina maintained resilience throughout the pandemic, launching a campaign on urban biodiversity in Rome, Italy, and interning for PennEnvironment to promote better state environmental policy. When she’s not getting her hands dirty weeding and harvesting produce, Maria enjoys baking, cooking, running, and grabbing coffee with friends. |

| Barlow Herbst (he/him) Rushton Farm Intern Barlow is a recent graduate of Harriton High School, and he is headed to Colby College in the fall! This is his second year interning at Rushton Farm. Prior to his internship, Barlow participated in the Rushton Bird Banding Program. Barlow has been birding for four years which is how he discovered WCT and all we do. He initially started with saw-whet owl banding and eventually began volunteering at Rushton Farm. When he’s not in the fields, Barlow stays busy practicing guitar, rowing crew, and doing ceramics. |

BIRD CONSERVATION & NORTHEAST MOTUS COLLABORATION

| Chris Regan (he/him) Conservation Associate Chris Regan joins our Bird Conservation Program with plenty of field experience and a degree in Wildlife Science from the State University of New York College of Environmental Science & Forestry. In addition to his time working as a Piping Plover steward for New York State Parks and later as a Field Technician for the Town of Hempstead Conservation & Waterways Department where he banded Oystercatchers, Common Terns, and Tree Swallows, Chris has also studied biomass regeneration and carbon sequestration of various hardwood tree species. Here at WCT, he will be assisting the bird banding team with their MAPS Banding operation and helping Shelly Eshleman’s Eastern Towee research. When he’s not banding birds, you can find him with other bands — The Meantime and The MovieLife — playing shows throughout the Northeast. |

| Victoria Sindliner (she/her) Conservation Associate Victoria Sindlinger is a recent high school graduate, and come fall, she will be pursuing a degree in Environmental Science at the University of Pennsylvania. Before then, she’ll be working here at WCT as an Avian Field Research Technician, where you can find her assisting Shelly Eshleman’s Eastern Towhee research, participating in grassland bird surveys, and taking on other field research duties as they come up. Victoria is no stranger to WCT’s Bird Protection Program, having volunteered with both migratory songbird and saw-whet owl banding at the age of 12! A bird-lover through and through, she is also devoted to the Delaware Valley Ornithological Club, Wyncote Audubon, the eBird review team for Philadelphia County, and Bird Safe Philly. |

STEWARDSHIP

| Will Steiner (he/him) Stewardship Intern Will Steiner is a senior who attends Ursinus College and studies marine biology. Prior to joining us in 2022, Will participated in a few research trips during his time in school. Will is looking forward to gaining experience from working with the Stewardship team and engaging in hands-on conservation work. After his internship is complete, Will plans to finish school and continue to seek biology and conservation-related opportunities. Out of the field, Will spends his time drawing and hitting the gym. |