Every four weeks, the Watershed Protection Program heads over to East Goshen to visit two branches of Ridley Creek near the Goshenville Blacksmith Shop. We trudge down the road to our first site, RC1, which lies in the main stem of Ridley Creek. We hop in the creek, take measurements, collect samples, and then we walk about 150 feet to our next site, WBRC1, West Branch Ridley Creek, where we do it all over again. Even though these two sample sites are right next to each other, WBRC1 is in a completely different creek. Just downstream from these two sample sites, the West Branch merges into Ridley Creek, and the waters from the sample sites flow together as one.

In many ways, these two streams are identical. The amount of water flowing through them is nearly the same. Also similar in size is the size of land they drain. Their banks are lined by both trees and shrubs, with a few patches of clearing. The stream beds are rocky along with some sand and mud near the banks. Given all of these similarities, it would be easy to imagine that the water quality is similar at these two sites, as well.

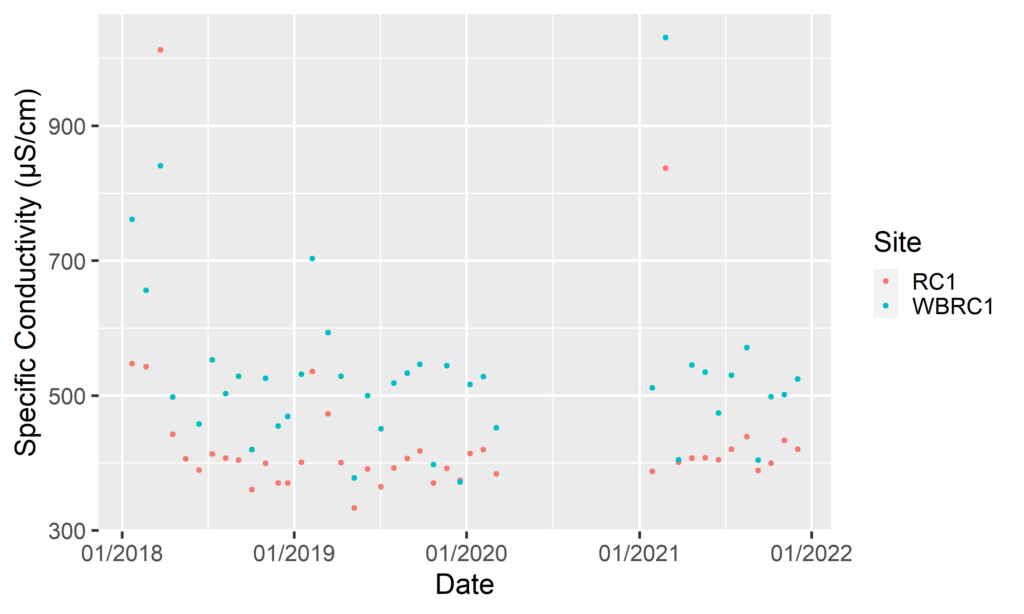

However, as the Watershed Protection Team discovered, once we started looking at the water chemistry, we found that the two streams are quite different. Immediately, we noticed differences in specific conductivity. Specific conductivity measures the ease at which electricity can move through water, and pure water is a terrible conductor, meaning it has low specific conductivity. So when we find that specific conductivity is high in water, then that tells us that there are pollutants present. Comparing WBRC1 and RC1, we found that the specific conductivity is much higher in WBRC1 than RC1, meaning the water quality is much lower in WBRC1. However, specific conductivity cannot tell us which pollutants are in the water–it can only indicate that there are pollutants.

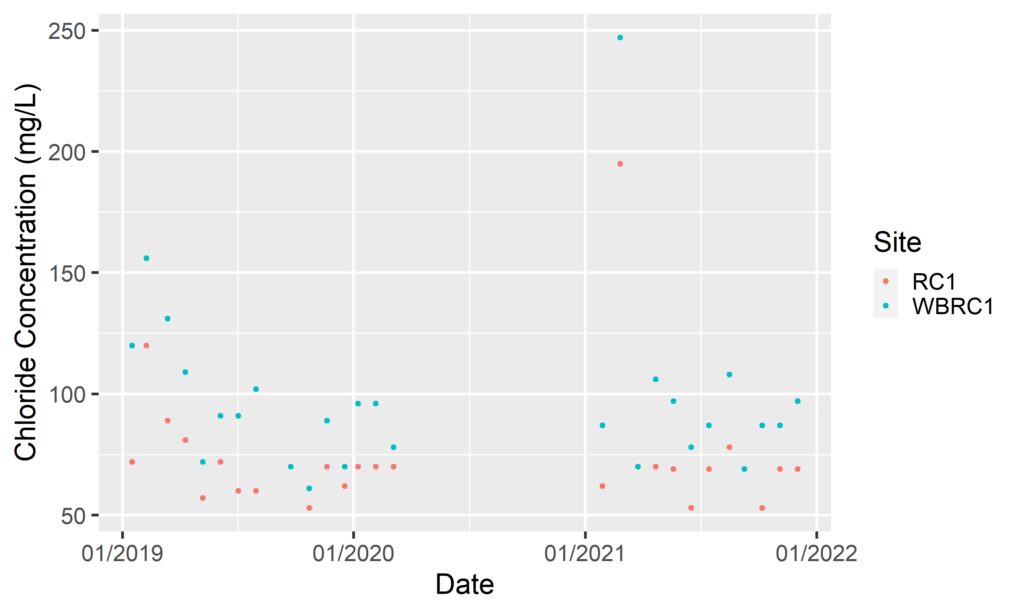

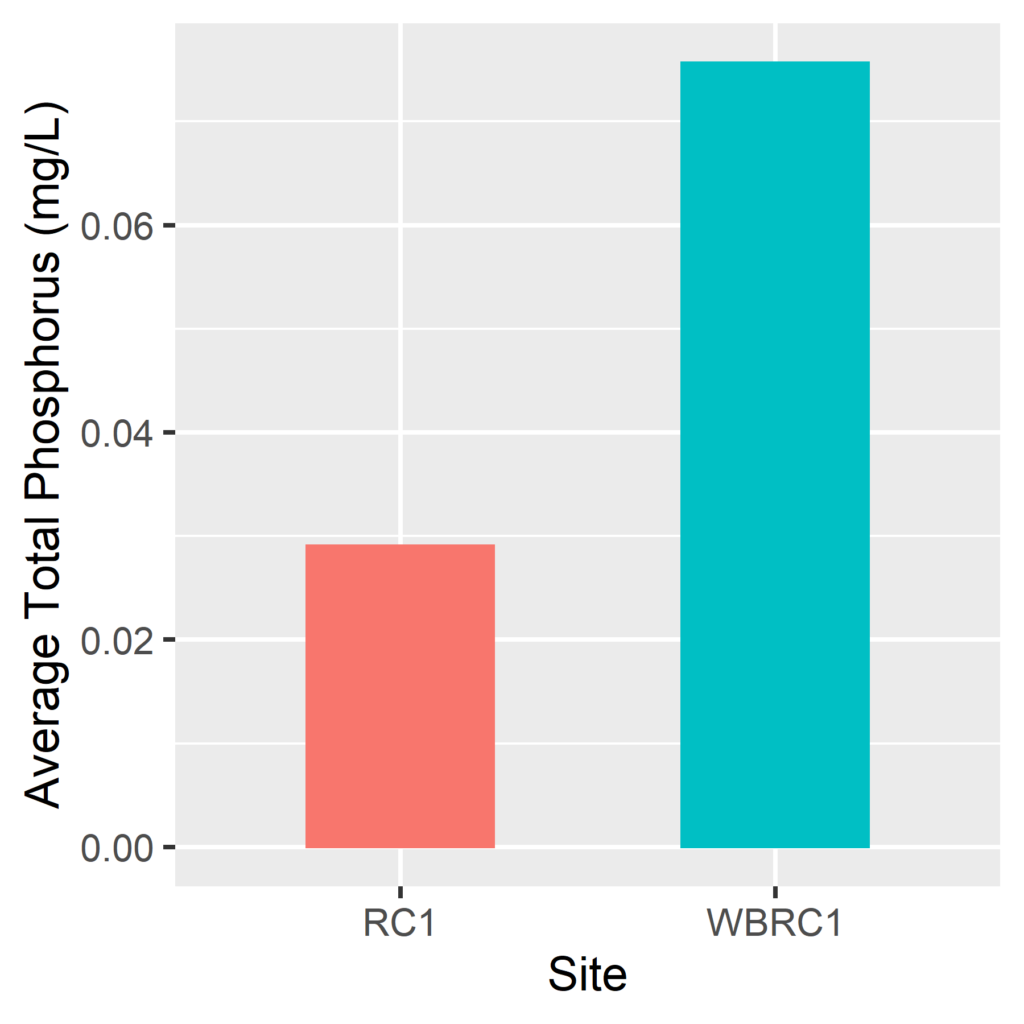

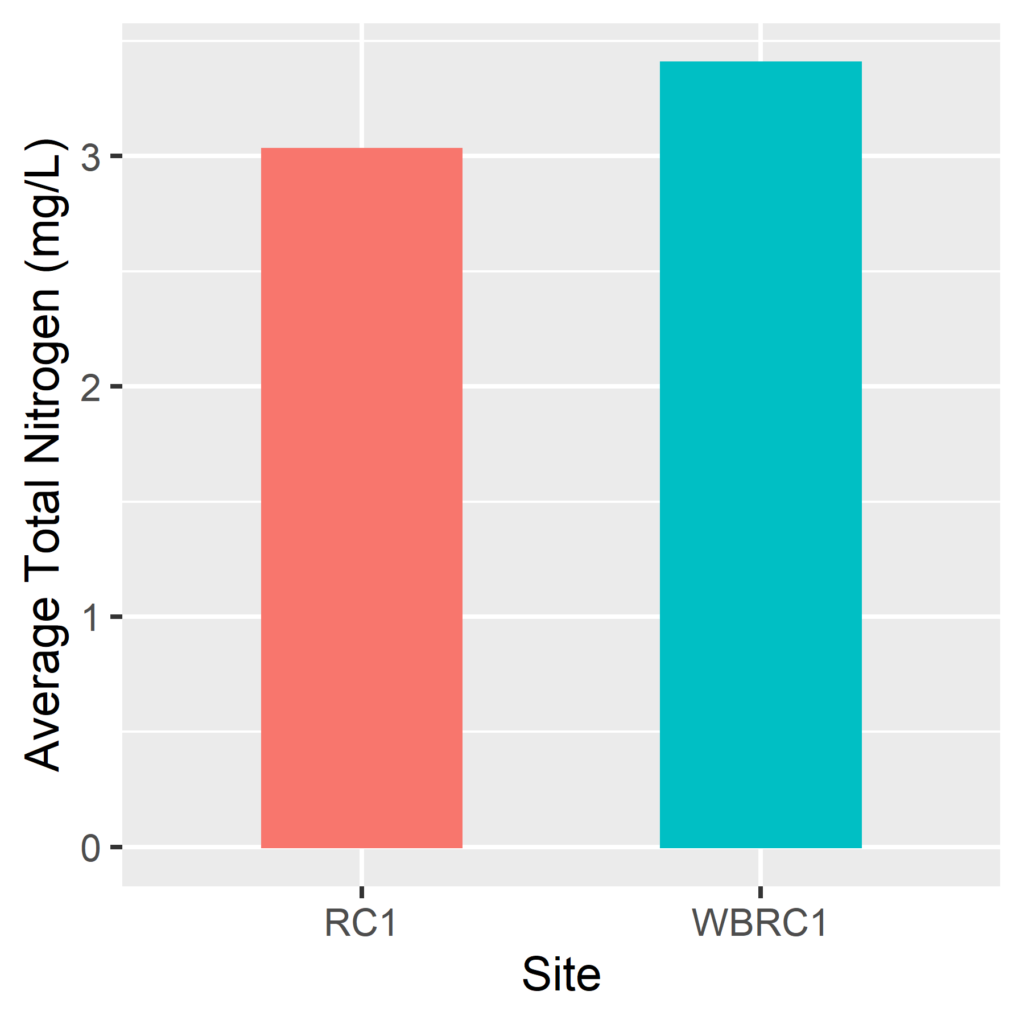

Looking deeper into the chemistry, we found that WBRC1 contains higher concentrations of chlorides, nitrogen, and phosphorus, all of which increase specific conductivity. So where are they coming from? For chlorides, the answer is road salts. After road salts are applied in winter, they runoff into streams and groundwaters, where they can persist throughout the year, leading to higher concentrations of chlorides year round. For nitrogen and phosphorus, the answer is a little more complicated. They can come from a few different sources, most commonly fertilizers, leaky septic and sewer systems, and animal waste. Elevated concentrations of chlorides, nitrogen, and phosphorus are concerning because these pollutants can threaten the survival of sensitive stream organisms, such as mussels, trout, and stream insects.

However, this poses more questions: why are there higher concentrations of salts and nutrients at WBRC1? How could water chemistry at two sites only 150 feet apart from each other be so different? To understand where these contaminants are coming from, we needed to look at what is going on in the land upstream of each sample site. And what we found is a difference in impervious surfaces.

Impervious surfaces are any surfaces that water cannot directly pass through, such as roads, sidewalks, parking lots, driveways, and buildings. These surfaces have several direct and indirect impacts on water quality. Many impervious surfaces are treated with road salt in the winter, and any rain or snow that hits these surfaces will carry that salt into the stream, increasing chloride concentrations. Impervious surfaces also reflect human activity in an area. Generally, the more impervious surfaces in an area, the more humans, and with more humans comes more fertilizer applications on lawns and gardens and more septic and sewer systems, all of which can flow into streams. As a result, there is a strong relationship between the amount of impervious surface cover and the pollutants that drain into a stream system.

We found that of the land that drains into WBRC1, 20% of that area is covered by impervious surfaces, as compared with RC1, where only 14% of the area is covered by impervious surfaces. While 6% may seem like a small difference, it is large enough to account for the difference in water quality of these two streams. This tells us that for Ridley Creek to maintain its health and water quality, we need to strive to stay below 20% impervious surfaces, and maybe even less than that.

The story of these two streams can be a hopeful one, and there are many lessons to be learned. If we can keep the amount of impervious surfaces down, we can protect water quality, even at an incredibly local scale. The more land we can protect as open space, the better the water quality in our streams and rivers.

In addition to protecting land, we as individuals can also reduce the impact that impervious surfaces have on streams by doing the following:

- Limiting the amount of road salt used in the winter or sweeping up road salt after storms pass. This is a great way to reduce the amount of salt entering streams.

- Reducing fertilizer use and avoiding applying fertilizers before rainstorms.

- Planting rain gardens alongside roads and driveways to help collect and filter stormwater, further reducing the amount of salts and nutrients entering streams. Native flowers, shrubs, and trees are great at absorbing excess nutrients and salts before they enter streams, and planting more of these plants will go a long way towards improving water quality.

- Finding more tips here: Healthy Streams Start with Healthy Landscapes.

No matter how far away you are from a stream, any action you can take will make a difference.

— By Watershed Conservation Associate Anna Willig

Sources:

Baker, M. E., Schley, M. L., & Sexton, J. O. (2019). Impacts of Expanding Impervious Surface on Specific Conductance in Urbanizing Streams. Water Resources Research, 55(8), 6482–6498. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019WR025014

Morse, C. C., Huryn, A. D., & Cronan, C. (2003). Impervious Surface Area as a Predictor of the Effects of Urbanization on Stream Insect Communities in Maine, U.S.A. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 89(1), 95–127. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025821622411