All photos are currently on display and for sale in the Rushton Conservation Center, May 17 – August 28.

INTRODUCTION BY OWEN MCGOLDRICK

The color photographs were made using a 4×5” Linhof view camera. Notch and clip marks are shown to emphasize a bygone era, which involved carrying a heavy view camera and tripod, loaded with Kodak or Fuji film, and taking a picture somewhere on the grounds of what is now part of the Kirkwood Preserve, or in the very accommodating and voluminous interior of our mid-19th century farmhouse and barn.

“Silo Cap” was one of the very first photos shot with a 35mm Pentax for a beginning photography class at the Columbus College of Art, Ohio. Our family lived in the lower house of Massey Farm (always referred to as White Horse Farm by our clan) from 1963 to 1990. The photographs in this exhibit depict the house, barn and fields that surrounded the fence line.

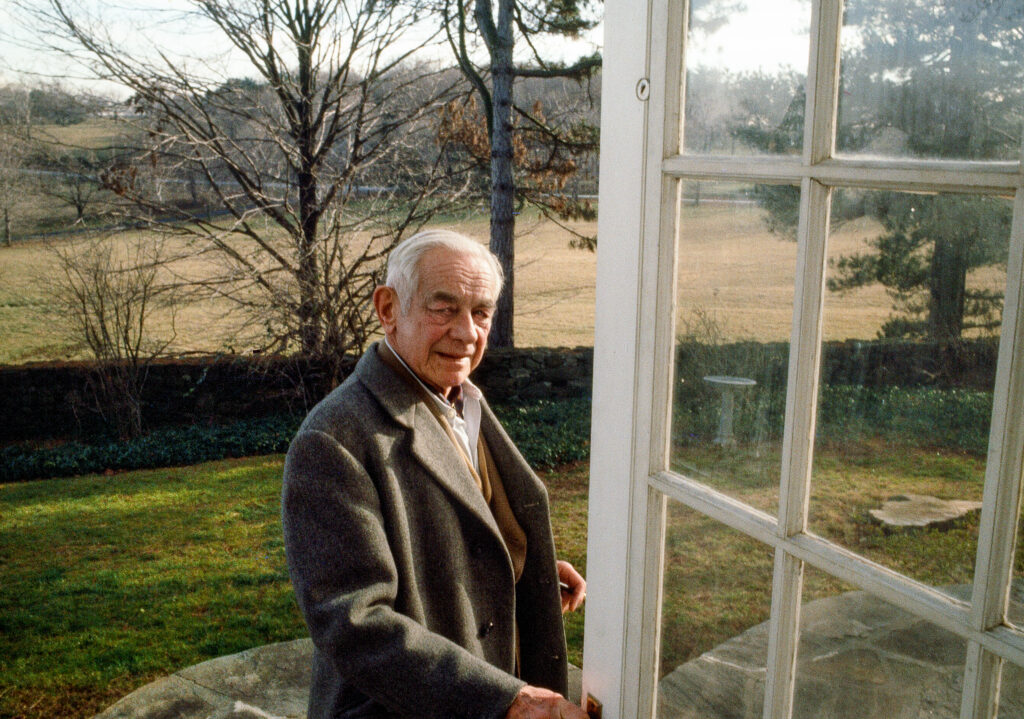

The landowner, Dr. Robert Strausz-Hupé, lived in the mansion at the top of the hill. He was an Austrian immigrant with Old World ways, a plume of cigarette smoke and cravat. He served as a statesman, professor at Penn and a term as the US ambassador to NATO, as well as Turkey, Sweden and Sri Lanka. Dr. S. H. could be stern, especially when it came to our lawn mowing abilities, or lack thereof; however, he was also generous, allowing us to use his glamorous swimming pool every summer day from 5 to 6 pm. What a relief it was to jump into that cool water on a hot, muggy summer afternoon. The pool was surrounded on three sides by apple trees which offered useful content for two of the pictures in this exhibit, not to mention homemade applesauce.

Here’s a tidbit. Mrs. Strausz-Hupé once called my mother and asked frantically if we had a car to pick up Dr. S. H. and a military general at the Philadelphia airport. Being the only resource available, off I went to pick up the good doctor and General Alexander Haig in the family VW. As a longhaired 16 year old with limited driving experience, it was a bit soon to be chauffeuring major political figures of national importance. After I dropped them off, mom asked me what they talked about. I replied, “Mostly themselves.”

Tidbit #2. Dr. Strausz-Hupé had an aesthetic streak. He was the first person to turn me on to the 18th century British artist and poet, William Blake. There we sat in his study with little hippie me looking at color plates of this visionary artist. Blake is still one of my favorite historical figures, and not only visually, but the whole daring philosophy of his creative universe is something to behold.

Growing up on a farm with a big barn to play in, acres of fields and woods to explore, and Crum Creek to swim and fish in, was more than a fair deal for any childhood. How remarkable it is that those fields and creek are today’s Kirkwood Preserve! Deep appreciation and a little awe goes to Bonnie Van Alen, Kate Etherington, Willistown Conservation Trust and the active group of local citizens for taking action and saving the day.

The select group of images were recently scanned and retouched in Lightroom and Photoshop and printed within the last two months on Epson Premium inkjet and Kodak professional paper. This is known as “straight photography,” where all effects happened on site and outside the camera, without machinations in Photoshop to create the visual results. The transparencies came out of a 40-year hibernation in carefully stored boxes through many a move, and now my old friends have returned.

GALLERY DESCRIPTIONS

All gallery photos are on display and for sale at the Rushton Conservation Center, May 17 – August 28.

1. The Barn is a Camera | A window shines a sunbeam inside the west storage room, or hay mow.

cam·er·a ob·scu·ra : a darkened box with a convex lens or aperture for projecting the image of an external object onto a screen inside. ORIGIN early 18th century: from Latin, ‘dark chamber.’

2. Silo Cap | One of the earliest photos from the first year of photography at the Columbus College of Art and Design. I wished I’d thoroughly documented the silo since we have so few photos of it. It was demolished later that year in 1977, after being deemed an unsafe structure.

3. Inside Looking Up | Inside the silo looking up at the deteriorating rooftop. A worker would have stood on those steps and lifted the sileage from the outside on an “elevator,” which was actually no more than an iron bucket. Dangerous work.

4. Black and Light | The result of a photography assignment using Dektol as a developer for B&W film. Or was it M-D3? It gives a grainy, high contrast look to the print. I took two negatives and sandwiched them. The barn’s a camera, a playground, a studio, a subject, an object.

5. Northwest Side | I took this snapshot in the mid-1990’s. Those doors are usually called “X-braced” and lead into the upper threshing room. The double decker barn traces back to English antecedents. A recent shot of one of the storage rooms is shown below.

6. The Exemplar | I remember floating by that oak tree in a great flood in June, 1968. There was a continuous wave at the bottom of Barr road.

Crum Creek was flowing to the right of this tree at about a 5-foot depth, a moving lake 10 times its normal size. That’s when I went for a swim and my friend Tom thought I was drowning so he made Boy Scout signals on the edge of the field. You can still see the high water mark from that storm event, put there by the township on telephone poles.

7. Pennsylvania Landscape | “Tootsie Roll” bales somewhere on Davis Road looking south. Archetypical Pennsylvania farmland nostalgia. For some reason, I think of the Civil War when I look at this print.

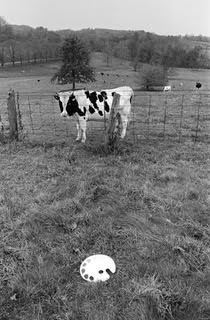

8. Cow Palette | Living amongst the Holsteins brought up mischievous thoughts of the black and white tonal scale in photography. But I didn’t expect the cow to be waiting for me on top of the hill. Hello Ansel Adams Zone System. That’s Crum Creek in the far ridgeline.

9. Speed of Light | From the third floor west bedroom looking into Wyeth country.

10. A Single Excellent Night | The title comes from the name of an ancient Buddhist text. That’s a 35mm slide projected from a Kodak projector of a TV still shot (was it a Magritte documentary?) into the far room. I painted the walls yellow and asked a friend to pose with an umbrella. She put on my bowler hat. I wish I still had that bowler hat.

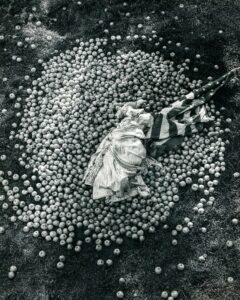

11. Flag Composition | Still life arrangement courtesy of the Strausz-Hupé apple grove. The antique dress was courtesy of mom’s shop in Berwyn. It was a lot of work to get those apples into our enclosed yard in cosmic order. The flag was a family heirloom from family ancestor and WWI flying ace, George Evans. One time I showed the photograph to the father of a very good friend who exclaimed, shocked and angry, “But that’s desecrating the flag!” (The flag should never touch the ground, let alone decaying apples.) You can’t predict some people’s reactions. But I got his point.

12. Thornley Bush III | I found this natural oddity and stuck it between barbed wire and a fence rail just outside of the mudroom. One time the field behind caught fire from an unmonitored rubbish burn and the fire department had to be called out to douse the flames. The next year the field grass grew back very, very green and healthy. Sometimes calamity brings an improvement.

13. Still Life with Moonrise | A Kodak projector beams a slide of the moon in the third floor bathroom. I was big into projecting slides into interiors and exteriors, and then photographing the on-the-site collage with a view camera. That’s called analog. Ya dig?

14. Three Tree Hill | A saddle sloped hill that was great for tobogganing. Brought to you by billions of years of tertiary history and a 4×5 view camera. Somewhere near those trees I remember there was a salt block for cows. After some research, sodium in the salt helps with the absorption of calcium and helps to avoid “grass tetany.” I tried licking that maroon colored block once as a kid and never did get grass tetany after that.

15. Priest at Crum Creek

Crum Creek. I wonder what the Lenni-Lenapes called it?

This is a shot of Father Dinda launching a toy boat. He was a real fun character who used to come into my mother’s antique shop in Berwyn. Mom would always have some interesting items in the shop and that’s how I came to borrow the boat. I love Father Dinda’s self-satisfied grin – a man of the cloth comfortable in his…cloth. How I got him on that rock I’ll never know.

We used to go swimming in one spot called the Sheep hole, where the creek was six feet deep. There was a rope swing on a pine tree, and swing we did into beautiful Crum Creek. I would get a stick and put a piece of bacon on a hook and fish from a large rock. In those summer days in the 60’s, I’d often see rainbow trout, which was always tantalizing because not once did I ever catch a trout with bacon. They don’t go for worms either. I’d inevitably catch a sunfish. This was Huck Finn style fishin’. One time I took my catch home and put him in our aquarium. We called him/ her, Sunny, he/she lasted all summer.

Right across from the big rock where I always sat, there was, and thankfully still is, a magnificent oak tree. Around the time I took Father Dinda’s picture, I set up the view camera in front of a tree in all its autumnal glory, The Exemplar.

16. Portrait of Father Dinda

17. White Horse Farm, 1900 | The house on the hill is the mansion where the Strausz-Hupé family lived.

From the Chester County Historical Society Archives.

18. The Lion in Winter | The home had a great fireplace. An excellent home for the holidays.

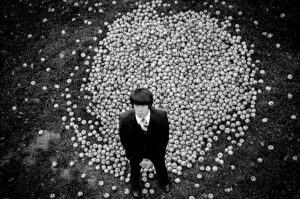

19. Beatle John | My brother John Pancoast posing in front of the apple cosmos in Alfie’s yard. It could have been a great album cover. John used to go to parties and tell everyone he was George Thorogood’s brother. It worked.

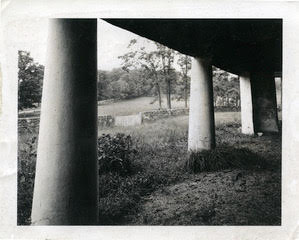

20. First Polaroid: Forebay | A copy of the very first Polaroid trying out a new view camera in 1981. Perspective issues!