As we approach the last few weeks of summer heat and humidity, we approach peak seasons for thunderstorms and flooding. Last Thursday, heavy rainfalls led to the first major flood of the year in our area. At Ashbridge Preserve, Ridley Creek rose over 2 meters (7 feet) in about 3 hours, pouring out of its banks. In the wake of these floods, we wanted to take the opportunity to answer some commonly asked questions about the fundamentals of flooding.

What is a flood?

The United States Geological Survey (USGS) defines a flood as “any relatively high streamflow overtopping the natural or artificial banks in any reach of a stream” (USGS, 2019). In other words, a flood happens when a stream breaches its banks, resulting in water flowing over areas that are not normally part of the stream. Floods can occur for a number of reasons, from snow melt to rain to changes in tides. In our area, the most common cause of flooding is rain, often from summer storms, and snow melt after large snowfalls.

Ridley Creek before (left) and during (left) a flood at Ashbridge Preserve in 2018. Photos by author.

How frequently do floods occur?

Floods can occur several times a year, whenever rain or snowmelt causes a stream to overflow its banks. Small floods, when the stream barely breaches its banks, are more common than large floods when the water pours out of its banks.

The size of a flood is determined by the peak flow of a stream or the greatest amount of water moving through the stream during a flood event. Peak flow can be determined by measuring the height of a stream; it is the highest height during the flood event. Higher peak flows indicate larger floods and lower peak flows indicate smaller floods.

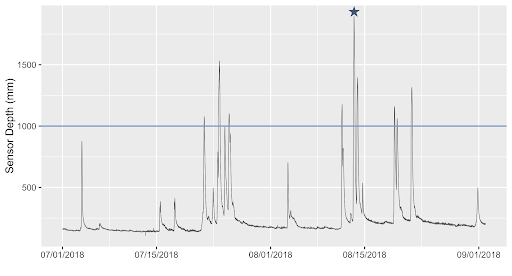

This graph shows water depth over time and nine floods that happened at Ashbridge Preserve in the Summer of 2018. The blue line represents the depth at which the stream completely fills its bank–a flood occurs any time the water rises above this depth. Each spike represents a rainstorm and the peak flow, which determines the size of a flood, is the highest depth in each storm. The star represents the peak flow of the flood that is pictured above.

Floods are classified by how often we expect them to occur. A 100-year flood is a flood of a given size that has a 1% chance of occurring each year. Similarly, a 500-year flood has a 0.2% chance of occurring each year and a 1000-year flood has a 0.1% chance of occurring each year. However, this does not mean that a 100-year flood will only occur once every 100 years or that a 1000-year flood will occur once every 1000 years. It simply refers to the likelihood of such a flood happening each year.

How do you stay safe during a flood?

Floods in our area can be dangerous, even life-threatening. According to a recently completed Hazard Risk Assessment by Chester County, flooding is the second highest risk hazard in the county. Floods can damage property, destroy roads and bridges, and threaten human lives.

Floodwaters are most dangerous for drivers, especially when drivers try to cross flooded roads. Twelve inches of flowing water will move a car, and 2 feet of water will easily sweep a car away. Even just a few inches of water can immobilize a car, stranding drivers in the middle of a road. If you are driving during a rainstorm, do not drive through any floodwater. Floodwater is often dark and murky, making it difficult to judge how much water is actually on the road and if the water is flowing. Turn around and find another route or pull over and wait until the water goes down.

Want to learn more about flooding?

Stay tuned next week for Flooding 102, which takes a deeper dive into how land use decisions impact flooding in our area. Until then, check out some of these resources:

- Monitor streams in Pennsylvania for real-time flooding: Streamflow conditions

- Check out real-time stream monitoring data in Ridley and Crum Creeks near Willistown: EnviroDIY Sensor Stations

- Learn more about flood risk and historical flooding in Chester County: Risk Assessment – Flood, Flash Flood, Ice Jam

- Learn more about how to stay safe during a flood: Turn Around Don’t Drown

USGS. (2019). Floods and Recurrence Intervals: Overview [Techniques and Methods]. USGS.

https://www.usgs.gov/special-topic/water-science-school/science/floods-and-recurrence-intervals?qt-science_center_objects=0#qt-science_center_objects