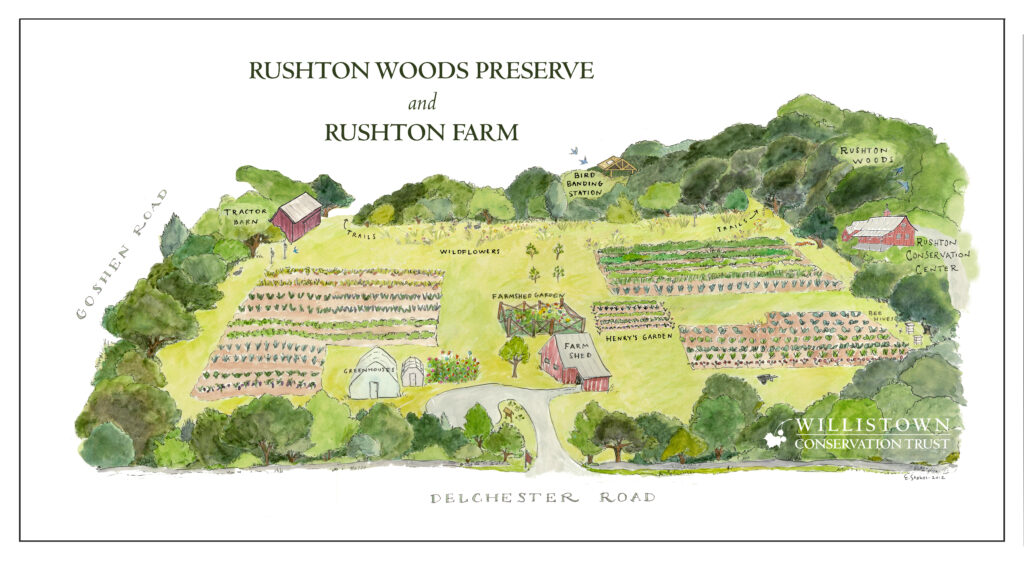

One Sunny midsummer day in 2012 on Rushton Farm, the bees decided to swarm. Noah, a certified apiarist–and the sustainable gardening manager teaching our cohort agro-ecology best practices–knew exactly what to do, and quickly sprang into action. He was able to quickly and safely locate the queen bee and remove the correct branch the swarm had formed on. It was a quick and mesmerizing event that created a lasting memory for all us interns and students who were there for the swarm…and then it was back to tending the row crops we were growing for the community supported agriculture (CSA) and food donations. It was a unique and fun way to work and learn, and an experience that would only have been possible due to the efforts of the Trust to not only create and restore the 6-acre sustainable farm but to make it accessible to us city dwellers and students that would have otherwise never known what existed beyond the hedgerows.

This experience reminded me of a time growing up in the Midwest. While playing outside in my backyard on a south facing slope, I discovered bees entering and exiting a nickel sized hole in the ground. Curious to see what they were doing, I went inside and got a jar. Then I put the jar over the hole, and for about 5 stings worth of time, or 20 minutes or so, I could study the bees. This event, like the swarm at Rushton, created an indelible and memorable window of observation that I would forever remember. As the interns and I worked with the staff and hosted student groups at the farm, I could not help but be reminded how such events can make a lasting and meaningful impact on young people as they begin to explore their natural world and make ecological connections.

As my internship progressed as part of the Penn MES program, the opportunity to study bees, and specifically native pollinators, arose. Working with Lisa Kiziuk and Fred de Long, I was able to reach out to bee expert Sam Droege from the Beltsville, MD bee lab. He assisted me with designing a baseline pollinator survey, told me where to get the glycol for the pan traps (painted yellow, blue and white solo cups with PVC holders) I would hand make and deploy in three areas around the farm, and even where to get the specimen collection bags and how to store the specimens for later ID (which Sam’s lab and interns there performed).

I would soon conclude my field research at Rushton after collecting the specimens from the pan traps throughout the summer and sending them to the Bee lab for ID. Thanks to the sustainable farming practices, focus on native plantings and abundant open space, we were able to identify 49 unique species of bees at Rushton Farm.

My capstone project at Penn would focus on deadly and pervasive insecticides and crop protection products called Neonicotinoids–which are used as seed treatments on over 95% of corn and soy planted in the U.S–and which were not used anywhere on Rushton Farm. At the end of 2012, after all the Rushton farm crops had been sustainably grown and harvested, I published “The Producer Pollinator Dilemma: Neonicotinoids and Honeybee Colony Collapse.” This project was the most in-depth project I’d taken on to date, and it began with “The Bees of Rushton Farm, A Pollinator Perspective on Sustainable Agriculture,” which was the independent project preceding the capstone, and where we published our baseline pollinator survey with the native pollinators we observed and collected in and around the farm that summer.

What began as a summer internship spurred a lifelong academic and ecological interest in native bees, agro-ecology, and how we can all work together to restore our land with an optimal mix of wildflowers, native grasses, and sedges. This is how the PollinatorPatch nonprofit campaign to restore One Million Acres, One Backyard Patch at a time, soon evolved from my new job with Applied Ecological Services as part of the large scale Restoration Field Crew in the Midwest, and then Project Manager for the Wetland Reserve Program in Iowa, in conjunction with the NRCS and State DNR.

It was during these projects and assignments that I realized a pollinator optimized seed mix was needed, by eco-region, and bloom period, and with more than the CP42 standard of 9 forbs (3 in each bloom period). On Earth Day in 2015 PollinatorPatch.com was launched to offer folks the best available 30+ species seed mix for their backyard and to show them why it’s important to help the bees, just like Noah did that one sunny midsummer day on Rushton Farm when the bees swarmed.

This past summer the entire experience came full circle when Monarch Joint Venture conducted a vegetation survey to see what native plants and wildflowers particularly were in bloom from a pollinator-optimized seed mix in the 3rd year of maturation.

“Everything is everything,” and we are all connected on our planet and by our collective actions. Small events can lead to bigger learning experiences and the unique and memorable outdoor education offered at Rushton is invaluable and makes bigger impacts in time thanks to the work of the Willistown Conservation Trust and its dedicated team.

Ben Reynard | was an Intern at Willistown Conservation Trust’s Rushton Farm in 2012. After earning a Masters’s degree in Environmental Studies at Penn, Ben went on to work for Applied Ecological Services as an Ecosystem Restoration Supervisor. Additionally, he has launched the nonprofit, Pollinator Patch to restore backyard habitat. Ben is father to a three year old son and is restoring a 3-acre goat prairie and an 1850’s pioneer cabin he hopes to make into an eco-home for his son to learn eco-homesteading and ecological restoration. To learn more about Ben and his path visit: https://www.linkedin.com/in/benjamin-reynard-03a4b358/ or https://www.lps.upenn.edu/degree-programs/mes/community/0514.