Although we did not venture out to track spring songbird migration at the onset of the pandemic this year, we safely resumed our efforts this fall and were handsomely rewarded. The total number of new songbirds banded from the end of August through October came to 939, even though we only operated the banding station twice a week. This brings our total number of songbirds across 11 years of banding at Rushton to over 15,000 individuals of 100 species!

The beginning of this fall produced copious warblers including elusive Connecticut Warblers, stunning Black-throated Green Warblers, and Black-throated Blue Warblers. September also brought us two new species for the station (never before caught) including a Cooper’s Hawk and Blue Grosbeak. The grosbeak’s presence at Rushton is another nod to the diverse habitat structure that Rushton Farm offers with its wild farmland borders, forest edges, and shrubby hedgerow habitat. To view more photos from the early part of migration see September’s blog post: https://wctrust.org/the-wings-of-change/

October reliably brought the sparrows —White-throated, Lincoln’s, Swamp, Field, Chipping, and Song—along with other winter treasures like a few Winter Wrens, a Dark-eyed Junco, and a handful of Purple Finches (an irruptive species that appears in our region in greater numbers some years than others). Slender Gray-cheeked Thrushes and long-winged Blackpoll Warblers are always exciting to band in late fall as they are some of our longest distance migrants breeding as far north as the taiga in Canada and overwintering in Central and South America. Missing from our usual October catch were Golden-crowned Kinglets, Brown Creepers, and the ever pined for Fox Sparrow.

Established in 2009 with a grant from the Delaware Valley Ornithological Club (DVOC), our banding station has been a huge success over the years, attracting many exceptional volunteers who help us run the station smoothly during spring and fall migration as well as during the summer breeding season.

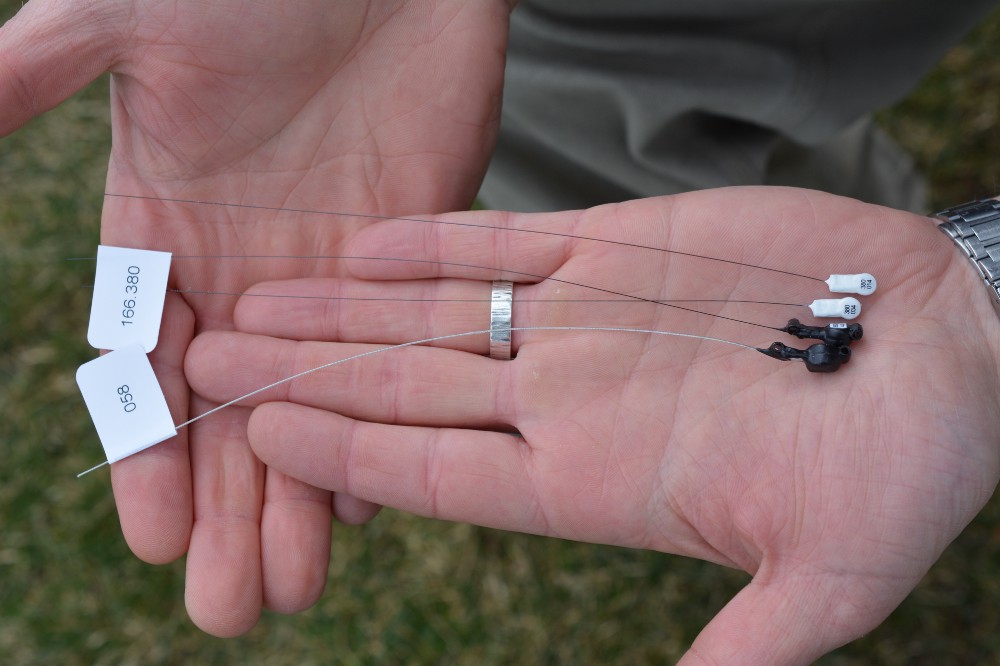

Our federally licensed bird banders operate up to 16 nets at a time, placing a unique aluminum band on each songbird. Tagging birds in this way allows us to: learn about presence or absence of species that are using our conservation farm and nature preserve; understand migratory behavior (like how long birds stopover in our habitat to refuel); reveal longevity and examples of site fidelity as individual breeding birds return to Rushton and are recaptured year after year; and explore other important population dynamics as well as habitat quality.

What follows here are some interesting highlights translated from the 10-year report that was compiled from our data by Alison Fetterman, Bird Conservation Associate.

Top 6 Most Abundant Species

Although we have banded 100 species at Rushton Woods Preserve, a few species dominate the landscape. These include: Gray Catbird, White-throated Sparrow, Common Yellowthroat, Wood Thrush, Ovenbird, and Song Sparrow. Catbirds take the cake numbering over 3,500 individuals through the years!

Rare Species

Over 10 years, there are 8 species that have only been captured once. While they are not necessarily rare migrants, their species-specific behavior (e.g., foraging in the tops of trees above our nets) may in some cases account for why these species rarely encountered our nets.

Bay-breasted Warbler

Clay-colored Sparrow

Cape May Warbler

Eastern Kingbird

Hooded Warbler

Louisiana Waterthrush

Yellow-bellied Sapsucker

Yellow-throated Vireo

Interesting Recaptures

Of the over 3,200 recaptures—birds captured that already had a band—only two of those birds were not originally banded by us. (This is a typical phenomenon for passive songbird banding.) These migrants included an American Redstart and an American Goldfinch. In addition, one White-throated Sparrow that was originally banded by us was subsequently recaptured at another station. Since all data for each bird is stored in a centralized database called the Bird Banding Lab, banders are able to acquire the birds’ stories from their band numbers:

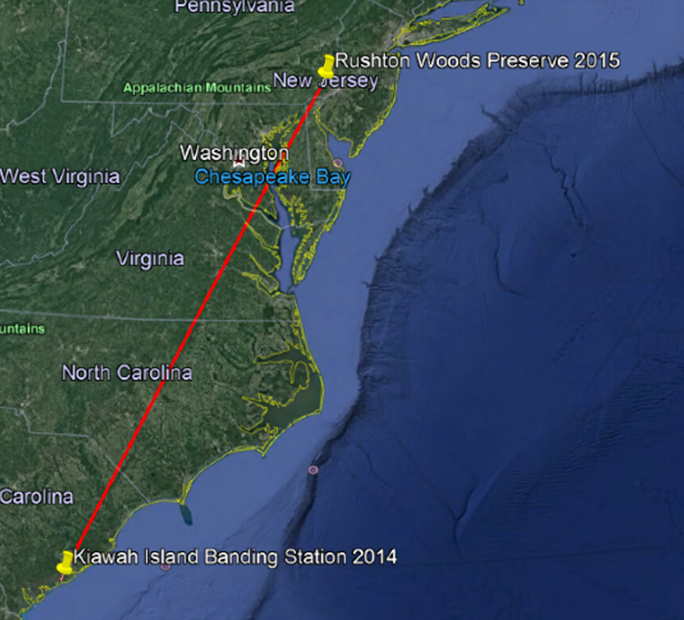

On September 3, 2015, we captured an adult female American Redstart at Rushton Woods Preserve (RWP). The bird was originally banded at Kiawah Island Banding Station (KIBS) in South Carolina in the fall of 2014 http://kiawahislandbanding.blogspot.com/. These banding stations are 570 miles apart and the bird was presumably on its fall migration when it was encountered in both years. These banding encounters contribute to our understanding of the migratory pattern of this small songbird.

American Redstart

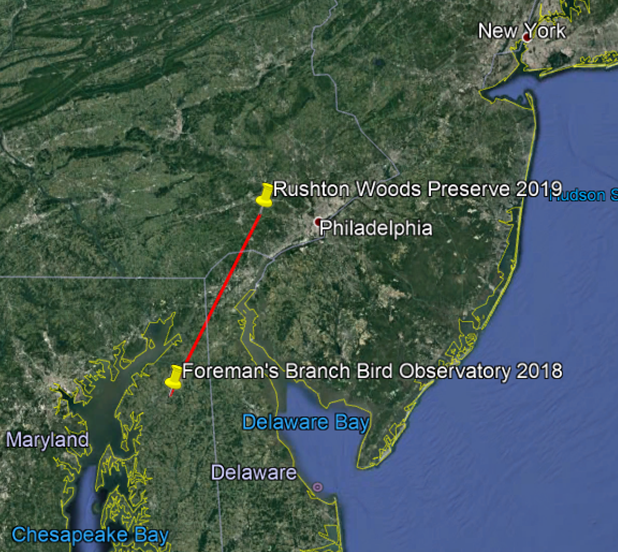

On May 1, 2019, tucked within a large flock of American Goldfinches we discovered a second year (SY) male American Goldfinch that had been banded originally at Foreman’s Branch Bird Observatory (FBBO) in Maryland on November 25, 2018. The young bird must have hatched in Maryland in the summer of 2018 and dispersed the 58 miles to Rushton the following spring!

American Goldfinch

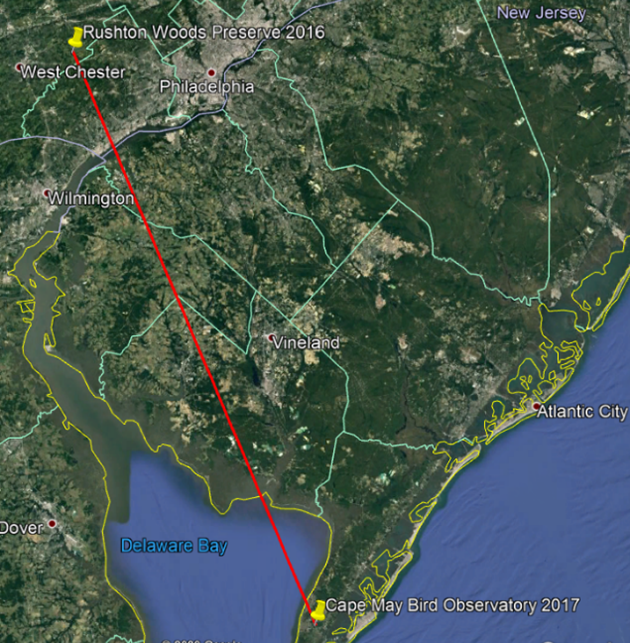

On October 16, 2016, we banded a White-throated Sparrow at Rushton. The following spring, on March 13, 2017, it was captured at Cape May Bird Observatory—75 miles to the southeast of Rushton Woods Preserve! One can only imagine that the bird continued south in the fall of 2016 after stopping at Rushton, and may have been picked up in Cape May during the north-bound spring migration. Alternatively, the bird may have used Rushton as an important stopover site on its way to its overwintering destination of Cape May, a hot spot for many birds.

White-throated Sparrow

Notable Weight Gains

Our data show that 75% of our birds are only captured by us once. Among the other 25% of recaptures, we have noted a few birds that stick around taking advantage of the habitat. When we recapture our birds we are able to record that they are gaining weight and using Rushton to fuel up for their next migratory flight. Songbirds only gain weight during migration in order to make long overnight flights.

As part of the banding process we look at subcutaneous fat stores, visible under the skin on a scale from 0-6, with 6 being the most fat. We also weigh the birds in grams. Through recapture data we can see how long birds may be staying at the preserve and their rate of weight gain for migration. Here are a few examples!

Veery : In early September 2017, we captured a Veery twice and discovered that the bird gained 14.9 grams in only eight days! This means the bird gained 47% of its body weight from the first time it was weighed, in only about a week’s time. A true athlete, this small thrush could easily have flown a couple hundred miles in one night following its final capture at Rushton Woods Preserve. It also means the bird was finding everything it needed at Rushton to fuel such a long journey.

Worm-eating Warbler: In the fall of 2015 we captured this bird three times between September 3 and October 1. (That’s 27 days!) However, this is a different example of an indication of good habitat quality. This bird did not gain weight between those catches like a typical migrant, but it was a young bird that most likely hatched that summer in a nearby dry wooded hillside—the preferred breeding habitat of this species.

After leaving the nest and its parents, it likely dispersed from the open woodland to the denser hedgerow and meadow habitat where we were capturing the warbler. The long length of stay rather, indicates that Rushton was providing important post-fledging habitat for this young bird and others—a shrubby early successional safe zone full of easy food, hiding places, and fewer predators for young birds learning how to make it in the world.

Longevity Records

After banding with a constant effort at Rushton Woods Preserve over the years, we can start to get a better idea of how long birds live and if they are returning from year to year. The Bird Banding Laboratory (BBL) keeps records of the oldest birds through over a million band records. However, after 10 years, we have a few records of our own.

Veery – At least 11 years old! This male Veery was first captured at Rushton on June 30, 2011, aged After Second Year (ASY), meaning it was at least two years old. We have since recaptured this bird breeding at Rushton in 2012, 2014, 2015, 2018, 2019 and 2020! We may not have seen the last of this old Veery! This is incredible when you consider that the Veery migrates to the tropics each winter. The BBL record for Veery is 13 years old.

Ovenbird – At least 11 years old! This female Ovenbird—another neotropical migrant—was first captured on May 27, 2011, aged ASY, meaning it was at least two years old just like the Veery. We have since encountered this bird breeding at Rushton in 2014, 2015, 2017, and 2020. The BBL record for Ovenbird is 11 years old, so we’re tied!

If you’d like to view the 10-year songbird banding report in its entirety, please contact us at bhg@wctrust.org. It will also eventually be available for public view on our website.

Wishing you the health and prosperity of our old birds and happy owl-idays!

As always, there’s a lot going on in the woods,

Blake