By Alison Fetterman, Bird Conservation Associate and Northeast Motus Project Manager

and Blake Goll, Education Programs Manager

“Oh Canada, Canada, Canada!” The wistful song of the White-throated Sparrow languidly drifts over the early spring landscape of our region, heralding the end of winter and the coming vernal equinox. Even those not attuned to individual avian sonatas can recognize these indelible notes punctuating the change of seasons. Humans are hard-wired for connection to nature, and birds provide that copacetic anchor. Watching them go about their day can make us feel grounded as fellow creatures of the earth; hearing them sing brings contentment and a sense of wellbeing; and admiring their colors and diversity ignites our curiosity and fascination.

We need birds. Not only for the joy they bring to our lives but for the life they bring to our world. They pollinate plants, disperse seeds, eliminate insect pests, and play a critical role in many different ecosystems. To an ornithologist or a bird bander, monitoring the population of birds allows us to take the pulse of the environment while measuring the success of science-based conservation initiatives and quantifying the value of land conservation.

Spring Bounty | Warblers and Woodpeckers | April and May are mirthful months when Rushton Woods Preserve (RWP) becomes a veritable jungle lit up with the tropical sounds and sights of the most delicate and breathtaking of the bird world: the wood warblers. These exquisite birds feed largely on insects gleaned from leaves, so their northward progression coincides with the leaf-out in our temperate throughway. Some will stay to breed in Rushton like the Ovenbirds, Common Yellowthroats, and Worm-eating Warblers, but most continue on to more preferable habitat or northward, as far as the boreal forest of Canada. Such passerby species included: Black-and-white Warbler, Black-throated Blue Warbler, Northern Waterthrush, Nashville Warbler, and Blue-winged Warbler.

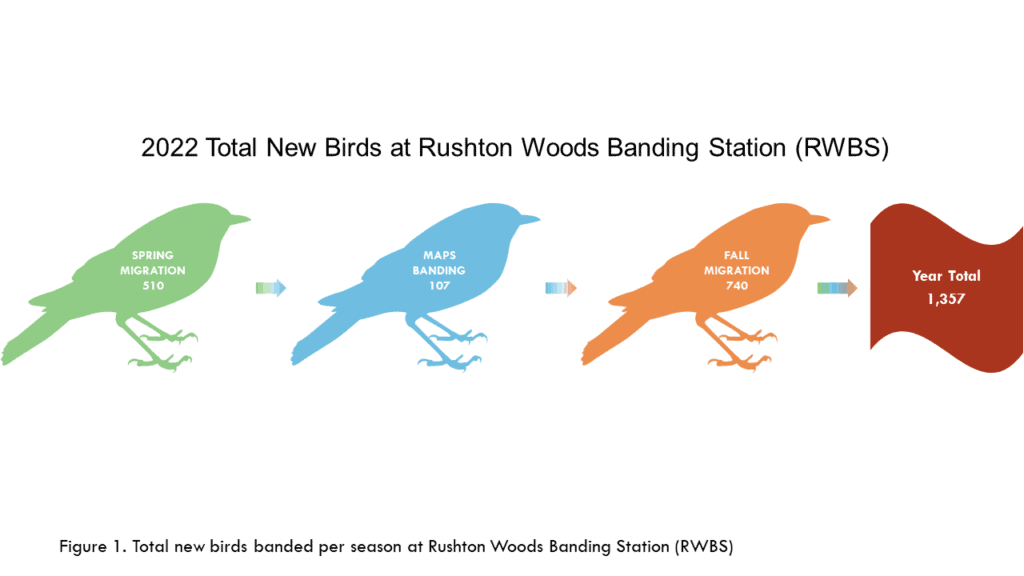

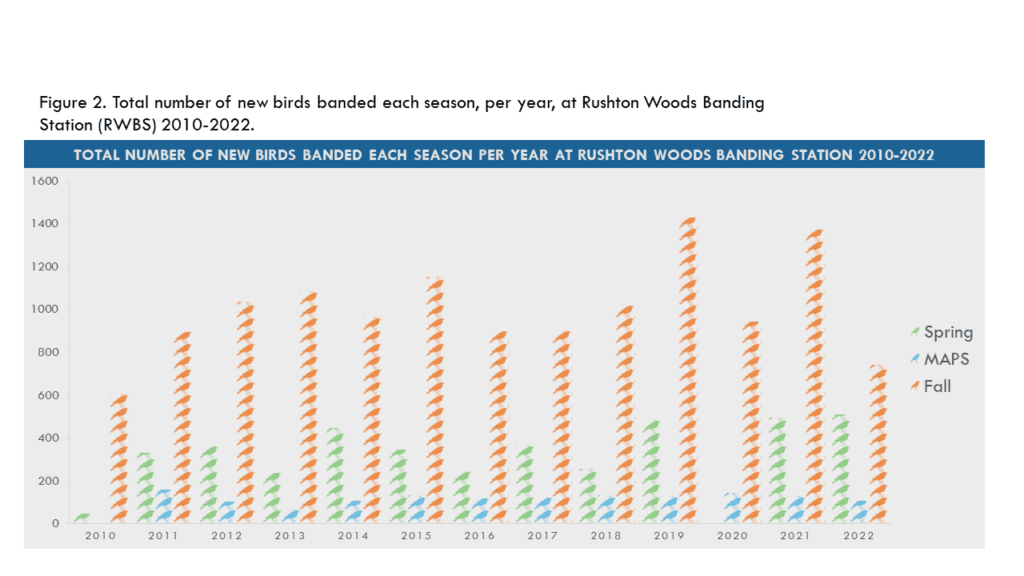

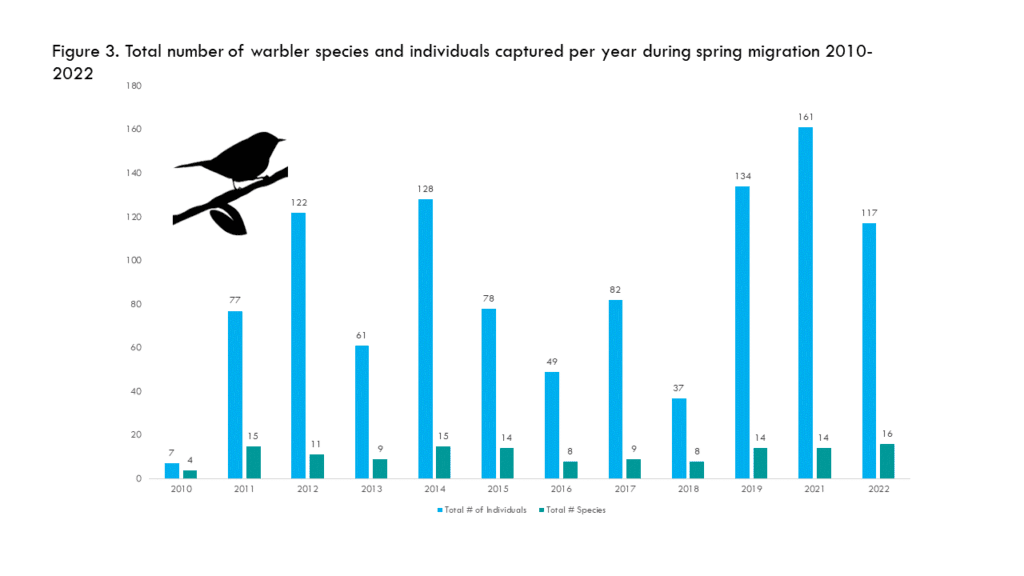

Overall, spring 2022 produced our highest number of individual birds captured in any spring for a total of 510 (Fig. 2), as well as the highest diversity totaling 55 species. This spring saw a record number of 16 warbler species, though not as many individuals — 117 compared to 161 in 2021 (Fig. 3). One of the highlights was a male Hooded Warbler (second ever for the station), resplendent in lemon yellow contrasting with his ebony hood. This is a bird that seeks mature coniferous woodlands for breeding, or wooded swamps with labyrinthian undergrowth. Under the cool hemlock trees it emphatically proclaims in a tone as clear and pure as the forest air, “tawee-tawee-tawee-tee-o!”

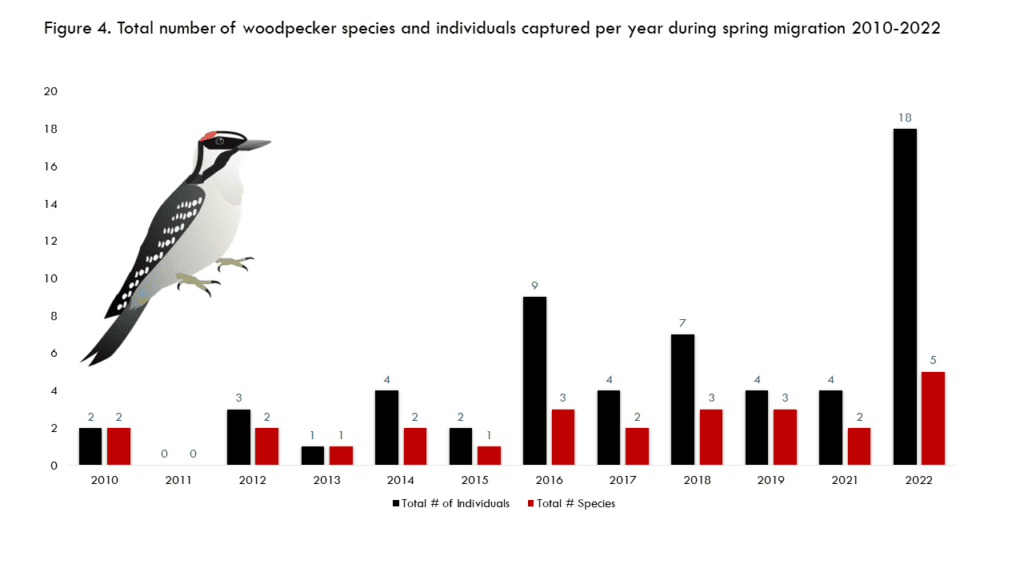

Another unique occurrence this spring was the significant number of woodpeckers. Not only did we catch all five breeding species (Downy Woodpecker, Hairy Woodpecker, Pileated Woodpecker, Red-bellied Woodpecker, and Yellow-shafted Flicker) for the first time ever in one season, but we caught double the number of individuals for a total of 18 (Fig. 4)! The increased presence of these birds indicates the habitat may be shifting to more dead standing trees — called snags — in the forest and hedgerows. Woodpeckers begin nesting early in the spring, so these individuals were likely already raising chicks in the snags.

Their unique ability to excavate cavities with their strong bills makes woodpeckers keystone species, paving the way for other cavity-nesting birds and mammals who do not possess the tools and talent to make their own. More than 40 bird species in North America depend on woodpecker carpentry for their nest and roost cavities. The woodpeckers’ need for dead or dying trees shows the importance of not over-tidying our landscapes; wherever they do not pose a threat to humans, dead trees should be left as vital components of the food web.

Summer Nursery | Cradle of Caterpillars | The end of May marks the close of spring migration and the start of the hurried nesting season. In the northern hemisphere, songbirds must take advantage of the relatively brief period of increased solar energy that allows for the creation of offspring — powered largely by the dazzling diversity of plant-eating insects. In particular, caterpillars are the herbivores that transfer more energy from plants to animals than any other plant-eaters. Birds, being experts at efficiency, capitalize on caterpillars because their large size and soft bodies make for easy energy packets for nestlings.

Caterpillars are also full of protein needed for nestling growth and antioxidants for plumage development and immune function. The only caveat is that caterpillars tend to be host plant specialists, having evolved over many years to be able to eat only one or two plant lineages to which they were exposed. Therefore, native plants hold the key to supporting population growth in birds. According to Doug Tallamy, author of “Bringing Nature Home,” one pair of Carolina Chickadees — a common breeder at Rushton — must find up to 500 caterpillars a day to rear one clutch. Chickadee parents attempting to raise chicks in a suburban neighborhood that is largely dominated by non-native ornamental plants have a greater risk of failure.

Rushton is one of more than 1,000 banding stations in North America participating in MAPS (Monitoring Avian Productivity and Survivorship) through the Institute for Bird Populations to understand breeding success of songbirds. Our 12 years of MAPS data show that we have 38 breeding bird species nesting in or around Rushton Woods, including State Responsibility Species such as the Wood Thrush and Scarlet Tanager. Our capture was relatively low last summer with only 107 individual birds (Fig. 2). With a record number of falling trees in the woodland habitat and plant communities shifting to non-native plants, the low numbers could suggest the habitat quality is deteriorating.

However, there are myriad other factors in a bird’s annual cycle that could also be affecting our breeding numbers, including natural fluctuations over time. For example, conditions on wintering grounds and migration routes can affect the survival rates and reproductive success of birds the following summer, a phenomenon known as “carry-over effect.” Analyzing such trends requires datasets that are broad in time and geographic scale, which MAPS as a whole offers with over 30 years of effort.

At Rushton, we strive to act locally to support this diversity of breeding bird species (and encourage landowners to do the same) by practicing land management initiatives that restore nature’s balance, often through plants. For example, our Land Stewardship Team removed a section of the Preserve’s hedgerow that had become heavily invaded with alien plant species and replanted this area with over 150 native shrubs and trees. These new native plants will act as caterpillar vending machines for our hungry breeding birds and their nestlings, just as neglected snags act as food web drivers. Vital habitat components such as these promote resiliency in our landscapes and productivity in birds.

A Quiet Fall | Honing Habitat | Besides productivity and survivorship, bird banding can estimate recruitment. This refers to the number of birds that survived life in the nest and are now out on their own as part of the adult population. Newly recruited “baby birds” bolster our fall catch significantly, making it typically our highest catch of all three seasons. Last fall, however, marked the lowest capture in our station’s history with only 740 new birds (Fig. 2).

One contributing factor for the low total could have been the unpredictable weather; we were forced to close the station for six days due to rain and/or high winds. Another question arises though; was there a regional lower recruitment of birds due to factors such as climate change, development, or habitat changes? Further research may help tease out some of these answers. One of the nuances of a bird’s annual cycle is that they require different habitats at different life stages. This is one of the reasons we try to manage the Preserve for a variety of habitats, especially early successional shrubland. This is the amorphous, often underappreciated plant community of shrub thickets, vines, and small trees that would naturally exist after a meadow matures and before it becomes a forest.

Photo by Aaron Coolman

Photo by Blake Goll

Photo by Aaron Coolman

Studies show that the structure of this type of declining habitat is exactly what many young birds seek during the perilous post-fledging period — the time after they have left the nest and before their first migration. For a young bird learning how to survive, early successional habitat provides an abundance of food, as well as denser cover from predators than open woodlands. Consequently, even a forest-dwelling species like an Ovenbird (a wood warbler that builds its nest on the forest floor) can be observed in shrub habitats after fledging. Many migratory birds also seek shrub habitats during fall migration for the bounty of berries — particularly those of native plants — that provide a rich source of fats and antioxidants needed for migration.

Therefore, in order to promote maximum recruitment of young birds as well as encourage migrants to stop over, we must maintain a healthy shrubland. Some indicators from our data — the increase in woodpeckers, the decline in some shrub-loving species like White-throated Sparrow, and our overall low fall catch — could suggest the maturation and deterioration of our shrub habitat and the need for targeted management. Replacing large trees and invasive species with native shrubs — a project that has begun thanks to our grant from Pennsylvania Society for Ornithology — will help improve the habitat integrity.

Bird banding can also reveal habitat integrity through recaptures. In addition to the 740 new birds banded last fall, 97 birds were recorded as “repeats.” These are birds already banded by us within the same season but caught multiple times, which allows us to calculate their weight gain or loss during stopover. For example, we recaptured one Ovenbird on September 14th that weighed 24.1 grams — an almost 25% increase in body mass from its original capture date on September 1st when it weighed only 19.4 grams. This may indicate that the habitat is satisfactory for Ovenbirds.

Some unique fall highlights included a beautiful Mourning Warbler in September, as well as a record number of five Yellow-bellied Flycatchers and three Cape-May Warblers. Cape May Warblers breed in the spruce balsam northern forests where they raise their chicks largely on spruce budworm. An eastern outbreak of this boreal pest may have contributed to a regional population boost for this warbler. During winter they can be found in shrubby gardens or even coffee plantations in the Bahamas and Greater Antilles.

THe People | Our banding station operates so successfully thanks to a dedicated team of staff and volunteers. The diversity of people who visit, study, and train at RWBS make our labor as enjoyable as the array of birds. In the spring, we hosted French banders from Tadoussac Bird Observatory in Quebec, as well as a drop-in bander from Israel’s Jerusalem Bird Observatory. In the fall, BirdsCaribbean sponsored Omar Monzon Carmona and Dayamiris Candelario to train for one month at RWBS to support the Caribbean Bird Banding Network. Another partnership with the Pennsylvania Game Commission allowed us to host a two-day intensive bird banding training workshop led by guest bander Holly Garrod from Montana.

Like the birds who return to Rushton, we hope we’ll see our old human friends again, as well. Birds connect us across continents, returning to the places that supported them and allowed them to thrive throughout their annual cycle. Capable of taking to the skies, they are still forever tethered to the earth — a reminder to us to remain loyal to our roots, bringing hope and healing to the land just as the birds do.

Resources:

- Institute for Bird Populations | birdpop.org

- Northeast Motus Collaboration | northeastmotus.com

- Rushton Woods Banding Station Annual Songbird Banding Report | wctrust.org/research

- Species Seen List | wctrust.org/birds/species-seen