If you’ve ever run a 10K, a marathon, or a turkey trot, you’ve probably pinned a bib to your shirt displaying your name and race number. If you’re like me, it was crooked.

Regardless, that bib helps race organizers keep track of participants: how many started, how many finished, who finished first, last, or not at all.

Scientists have long used a similar technique to help keep track of migratory birds. During fall and spring migration periods, ornithologists staff banding stations multiple days a week, catching birds and attaching small aluminum bands to their legs stamped with unique numbers, like tiny race bibs.

But there’s a big difference between tracking migrants and marathoners. Birds don’t have a start line, a finish line, or a marked course to follow with volunteers handing out energy gels and ringing cowbells along the way.

“After we band a bird, it could be any length of time before we see it again, if at all,” said Lucas DeGroote, Avian Research Coordinator for the Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Powdermill Nature Reserve in Pennsylvania, which has been banding birds since 1961. “We band 10 thousand birds every year, and only about two of those are recovered elsewhere that year,” he said.

Despite the low recapture rate, banding still provides valuable information to researchers. “It gives us a snapshot of populations, and helps us understand their responses to change,” said DeGroote. Say, if you invest in improving stopover habitat at a site, banding can tell you if the total number and diversity of seasonal migrants increases in response.

But banding doesn’t tell scientists where else birds go on their migratory journey, and why.

“The life cycles of migratory birds unfold over thousands of miles,” explained Lisa Kiziuk, Director of Bird Conservation for the Willistown Conservation Trust in Pennsylvania, who launched a banding station at the trust’s Rushton Woods Preserve a decade ago. “If we want to look at where the bottlenecks are, we need to see the whole life cycle.”

Given the dramatic decline in migratory bird species in North America, identifying those pinch points will be critical to ensure that enough stopover habitat is protected in the right places to support birds during these arduous journeys.

Fortunately, partners are gaining ground with new technology that tracks birds and other species along their migratory paths, wherever they may take them.

With support from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Pennsylvania Game Commission is leading a collaborative of two states and eight organizations to close a major geographic gap in the Motus Wildlife Tracking System, which uses nanotag transmitters and an array of radio telemetry receivers to study migratory routes and behaviors.

Part of the Northeast Motus Collaboration, the partners have been awarded a state wildlife grant to install 50 new receiver stations across New England — adding to the 46 being installed in the Mid-Atlantic states — all sited strategically to provide maximum coverage of key stopover locations based on NEXRAD radar data. The funding guarantees that the towers will be in place for at least five years, an important warranty for researchers who often need a year or two just to set up a study.

“Within the next decade, the entire region will be populated with stations listening for tags from wherever they’ve been deployed,” said Kiziuk, who is helping to lead the effort.

There will soon be a lot more to hear. While radio telemetry is not new in wildlife tracking, its use has traditionally been restricted to relatively large animals that can carry heavy transmitters, like hawks, snakes, and bobcats.

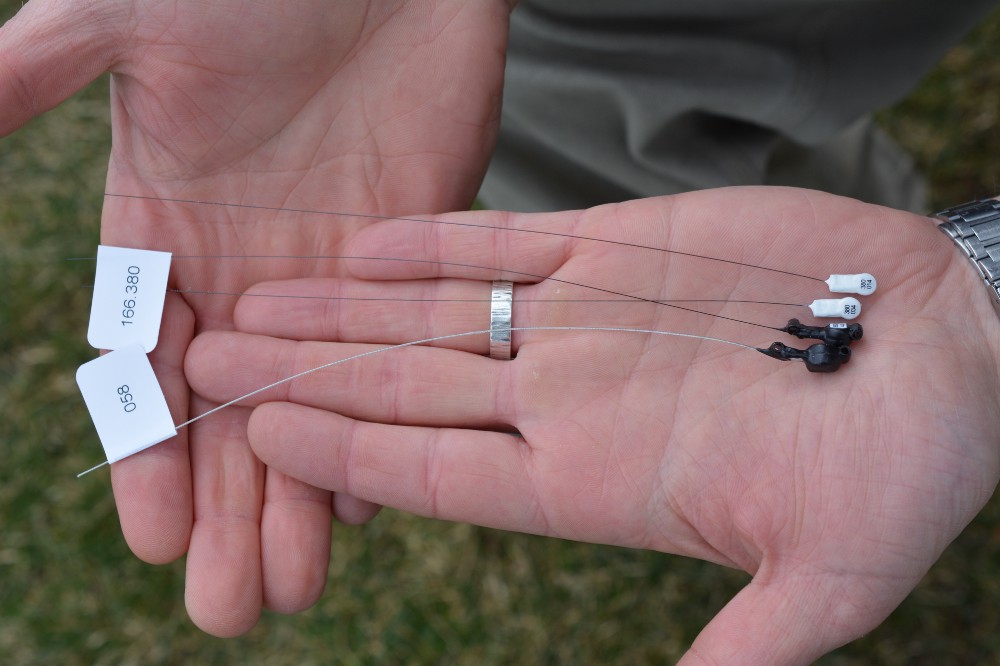

The nanotags deployed through Motus can be used on smaller species than ever, like the northern long-eared bat, Bicknell’s thrush, and even monarch butterflies.

“Each tag weighs less than three percent of the weight of the animal,” Kiziuk said. The tags can emit radio signals at distinct time intervals, like a Morse code signal identifying each individual.

Partners have already seen significant returns on investment. DeGroote said two-thirds of birds that have been nano-tagged in the project have been detected by towers, which are aligned latitudinally at specific intervals so they will pick up any individuals flying north or south across the region — sort of a proxy for runners crossing a start or finish line. “It’s a much better payoff in terms of detection while birds are moving,” he said.

That data on individual movement is a valuable complement to the population data that banding provides. Compare it to a race: If you are the director of a marathon, you want to know about how many people you can expect to register each year. But you also want to know how long it will take runners of varying skill levels to complete the course so you keep the roads blocked off for enough time, and you want to know where the toughest hills are so you can station volunteers at the top with energy gels and cowbells.

“Motus allows us to ask different questions by tracking individuals, and individual decisions, at different times,” DeGroote said. Questions that can help researchers address specific challenges birds face during migration, including one of the deadliest: One billion birds die each year because they fly into windows, disoriented by the reflection of the sky in the glass.

But what happens to the ones that get back on their feet?

“That’s where Motus comes in,” DeGroote said. “We can now track individuals that hit windows and survive to see what happens to them over time.”

His organization has equipped programs that respond to bird strikes in urban areas, like Lights out Baltimore, with nanotags to put on birds that are brought to rehabilitation centers after hitting windows, so they can monitor their survival and behavior when they are released back into the wild.

Dan Brauning, Wildlife Diversity Chief for Pennsylvania Game Commission and the grant project lead, explained that the ability to monitor individual birds lets us fine-tune how we measure this problem, and how best to respond. “As of now, the estimates of the impacts of collisions are based on finding dead birds,” he said. Those estimates don’t account for impacts to birds that take off and die later, or fly in the wrong direction because they are concussed.

“Motus can help us understand how big the problem really is, and the relative threat it poses to different species,” Brauning said. That applies to other problems too. By connecting the dots between threats and responses across time and space, managers can see where they need to act to address problems on the ground.

Just as important, Motus connects the dots between people who care about these problems, and empowers them to make decisions that reflect the landscape-level needs of migratory species.

Through the interactive map on the Motus website, participants can see the receiving stations, who owns them, and what species have been detected at each one. They can also see the conservation potential of having this regional data available at their fingertips.

“It shows what can be accomplished with a diverse group of people working together,” Kiziuk.

“Information is getting out there faster than ever, and can that can help us make better conservation decisions more efficiently,” she explained.

Ultimately, the effort to recover migratory species is not a sprint. It’s a relay between partners over thousands of miles, and collaboration is key to victory. Cowbells can’t hurt, though.

by Bridget Macdonald, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, North Atlantic-Appalachian Region