How is a small land trust like Willistown Conservation Trust helping the global effort to help birds? Take a look at our recent Instagram story!

How is a small land trust like Willistown Conservation Trust helping the global effort to help birds? Take a look at our recent Instagram story!

WILLISTOWN, PA (APRIL 20, 2020) — A major grant from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) will enable a research partnership that includes the Willistown Conservation Trust in Chester County, Pennsylvania, along with a number of state agencies and nonprofit organizations, to dramatically expand a revolutionary new migration tracking system across New York and New England.

The grant, totaling $998,000, has been awarded to a partnership led in part by the Northeast Motus Collaboration (northeastmotus.com), which includes the Willistown Conservation Trust; the Ned Smith Center for Nature and Art in Dauphin County; Project Owlnet, a nationwide cooperative research initiative; and the Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Powdermill Nature Reserve in Westmoreland County.

The New Hampshire Fish and Game Department is the lead agency, along with the Pennsylvania Game Commission, Massachusetts Department of Fish and Game, and the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife. Other partners include New Hampshire Audubon, Massachusetts Audubon and Maine Audubon.

The grant will allow the partners to establish 50 automated telemetry receiver stations in New York, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Vermont, Rhode Island, New Hampshire and Maine. These receivers will track the movements of bird, bats and even large insects tagged with tiny radio transmitters called nanotags — so named because they are tiny enough to be placed on migrating animals as small as monarch butterflies and dragonflies. The receiver array will be part of the rapidly expanding Motus Wildlife Tracking System (motus.org), established in 2013 by Bird Studies Canada, which already includes nearly 900 such stations around the world.

Together, the combination of highly miniaturized transmitters — some weighing just 1/200th of an ounce — and a growing global receiver array allows scientists to track migrants previously too small and delicate to tag with traditional transmitters, like a gray-cheeked thrush that made a remarkable 46-hour, 2,200-mile non-stop flight from Colombia to Ontario.

This is the second major USFWS grant for Motus expansion that the Northeast Motus Collaboration has received. In 2018, the agency awarded the collaboration about $500,000 to build 46 receiver stations in Maryland, Delaware, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and New York. The collaboration had already constructed a 20-receiver array across Pennsylvania in 2017 using private, foundation and state grant funds.

Besides significantly increasing the telemetry infrastructure across the Northeast, this new USFWS grant specifically targets several species of greatest conservation need in New England. Research collaborators will use nanotag transmitters to study the migration routes, timing and behavior of American kestrels, the region’s smallest falcon and a bird that has experienced drastic and largely unexplained declines across New England.

Other scientists will use the smallest nanotags to track the movements of monarch butterflies from the region, which have also suffered large population declines, but about whose migration little is known. The tracking information will help conservation agencies map the best areas to target for land conservation and habitat improvement, like encouraging the planting of milkweed for monarch caterpillars. Finally, researchers will also conduct testing to better understand the detection limits of newly developed versions of this new technology.

While the grant focuses on a few target species, the value of the expanded receiver network has much broader implications. Any nanotagged animal that flies within nine or 10 miles of any of the receivers will be automatically tracked.

“Conservationists are rightly concerned about kestrels and monarch butterflies, and the work funded by this grant that may give us answers that allow us to reverse their declines,” said Lisa Kiziuk, director of bird conservation for the Willistown Conservation Trust. “But by greatly expanding the overall Motus network, the grant will also provide scientists and resource agencies with a treasure-trove of information on dozens of other migratory species, from at-risk songbirds like Bicknell’s thrush and rusty blackbirds to rare bats that travel through the Northeast, and about whose movements we know little or nothing.”

“For me, this project is important because never before have we had the technology to see intimate details of an individual species’ migratory pathway in this way,” said Doug Bechtel, president of New Hampshire Audubon. “Motus technology and this particularly dense array that will be constructed in New England, especially in conjunction with the expansion in the mid-Atlantic states, will enable conservation organizations, industry leaders and legislative decision-makers to see how habitats are being used on a landscape level and make associated conservation decisions based on near real-time data.”

CONTACT INFORMATION

Lisa Kiziuk, Director of Bird Conservation, Willistown Conservation Trust. 610-331-5072, lkr@wctrust.org.

Scott Weidensaul, Northeast Motus Collaboration. 570-294-2335 (cell), scottweidensaul@verizon.net.

Willistown Conservation Trust, located in Chester County PA, is a land trust focused on preserving open space and habitat protection in the Willistown area. The Trust’s Bird Conservation team has operated the Rushton Woods Bird Banding Station since 2007, and has been a lead partner in the Northeast Motus Collaboration to save migrating bird species since its inception in 2016.

By Blake Goll

This fall, world scientists (11,000 of them to be exact) made a clear and unequivocal declaration in BioScience Magazine that planet Earth is in a climate emergency. The climate crisis is closely linked to excessive consumption of the wealthy lifestyle, and climate tipping points are arriving faster than anticipated. Major change is needed at all levels of society, and “help planet Earth” might be the most important New Year’s resolution to add to your list.

This sounds like a lofty task that could induce Ostrich Syndrome of sticking our heads hopelessly into the sand. Especially since this warning follows the article in Science declaring that we have lost 30% of our birds in the past 50 years. Do not despair: there are many personal changes we can all make in our daily lives, and by focusing on birds we can make the overall problem seem more manageable and the solution more tangible. When we help birds, we help the world.

Following represents a list of ideas to consider, realizing we cannot be perfect. But we can certainly be better.

While most of us cannot directly reduce subsidies to fossil fuel corporations as the Alliance of World Scientists suggests, we can reduce our carbon emissions personally. Planning a vacation for 2020? Try exploring a place closer to home rather than one that requires global air travel. Buying a new car? Choose brands with low emissions or electric if you can afford it. Look into changing your home energy supplier to renewable energy.

Studies show that climate change is playing a role in bird declines. As the planet warms, bird ranges are shifting north often into less ideal habitats. Some neotropical migrant species in particular have been hit hard because their day length-derived arrival dates are now out of snyc with temperature-derived North American insect pulses.

Check out the official climate emergency warning.

With lawns covering over 40 million acres of the U.S., it is paramount that we begin to see these lawns as places where conservation can happen. Devoting part of your manicured lawn to a natural meadow habitat with native grasses and flowers can greatly increase diversity of insects and birds, eliminate the need for pesticides, and reduce the need for watering (most native plants once established can mine groundwater). These native wildflower gardens only require mowing once a year in early spring, thus decreasing carbon emissions associated with repetitive mowing.

Doug Tallamy, author of Bringing Nature Home, proved that chickadees in a suburban neighborhood of mostly lawn and non-native trees and shrubs actually experienced diminished breeding success. Most of the nutrient-rich caterpillars they need to feed their young are located on native plants; Tallamy’s lab suggests that even an imperfect mix of 70% native plants and 30% non-native is enough to bolster healthy populations of breeding birds in our neighborhoods.

Visit the Native Plant Finder to learn which butterflies and moths are supported by different native plant host species in your area.

Reducing the global consumption of animal products, especially large livestock, can significantly lower greenhouse gas emissions. Enormous expanses of natural ecosystems are used for growing livestock feed. Eating a plant-based diet not only improves human health but it also frees up cropland for growing human plant food as well as for restoring natural habitats for birds, wildlife, and ecosystem services (e.g., carbon sequestration).

You can also support small farms like Rushton Farm that employ regenerative agriculture. More than simply organic, regenerative agriculture is a conservation and rehabilitation approach to farming and food systems. It’s partnering with nature to regenerate soil with smart crop rotation, increase biodiversity with habitat borders, improve watersheds by eliminating chemical inputs, and enhance ecosystem services like pollination by native bees. Basically, it’s the way farming was done prior to agricultural intensification.

Agricultural intensification has been linked to the worrisome 50% decline in American grassland bird populations since 1970. Worldwide, this sect of birds is dramatically declining in part because of farmland habitat degradation but also because of controversial insecticides previously thought to only affect bees.

A recent study on wild White-crowned Sparrows used Motus tracking technology to understand the detrimental appetite-suppressing effects of these neonicotinoids on migratory birds. Read more about the fascinating study: Insecticides Shown to Threaten Survival of Wild Birds.

Coffee traditionally grows in harmony with nature in the understory of tropical forests. This means that it is an agricultural product that can actually support a diversity of habitat structure that is perfect for migratory birds that overwinter in the tropics like our beloved Wood Thrush and Baltimore Orioles.

Unfortunately, much like the rest of modern agriculture, we have found a way to intensify this crop’s production by clear-cutting forests and growing it in the sun. Full-sun coffee farms make up over 76% of the total coffee cultivation area.

You can support family owned coffee farms that are doing it responsibly and preserving forests by looking for the Bird Friendly certification, a science-based certification that is run by the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center of the Smithsonian Institution. Bird Friendly requires farmers to plant a diversity of trees, prioritizing native ones that have the highest value (in insects) to birds.

Read more about the intricacies of the relationship between birds, coffee, and global warming: Newfoodeconomy.org.

And then order some Bird Friendly coffee from our friends at Golden Valley Farms Coffee Roasters in West Chester, PA!

The boreal forest of Canada has been dramatically affected by America’s love of luxury toilet paper brands that use virgin pulp. The boreal forest covers 60% of Canada, absorbs significant amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, and has been called the Songbird Nursery of North America as 3 billion birds of over 300 species flock there for breeding each year. An area the size of Pennsylvania has already been wiped out of this majestic forest.

There are many toilet paper brands that now use recycled paper and even bamboo, which is still far more sustainable than pulp from trees (and a little softer than recycled paper for those transitioning from pillow soft virgin paper). Who Gives a Crap and Seventh Generation are popular brands to try out.

Hundreds of millions of birds die each year from window collisions, but there is another human-induced threat that is even more sinister: cats. American Bird Conservancy states that cats kill approximately 2.4 billion birds each year in the U.S. alone, making them the number one human-caused threat to birds (next to habitat loss). We need those 2.4 billion birds, now more than ever, to help keep insect populations in check, which keeps forests healthy and mitigates global warming.

When allowed to roam outside in natural areas, cats are an alien invasive species that wreak havoc on bird populations that are already stressed due to habitat loss and climate change. When kept inside, cats are loving pets that live longer, healthier lives.

Looking for some interesting reading for 2020? Check out Cat Wars, by Pete Marra, which traces the historical ties between humans and cats and tackles this complex global problem.

According to Audubon science, two-thirds of all North American bird species are at risk of extinction without immediate conservation action. Bird conservation legislation can help prevent unnecessary bird mortality. Industry, for example, plays a significant role in bird deaths: annually, tens of millions of birds collide fatally with power lines and communication towers, 500,000 birds mistake open oil waste pits for lakes, and over 1 million birds perish from accidents like the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

The current administration has weakened important, long-standing legislation like the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, which held industry responsible for minimizing bird mortality (e.g., keeping covers over oil waste pits). Fortunately, a bi-partisan bill has just been introduced: the Migratory Bird Protection Act (MBPA). This bill will essentially revoke the free pass to incidental bird killing and create a permitting system for businesses to reduce preventable bird mortality.

Your voice can make a difference. Urge your representatives to co-sponsor this important bill on American Bird Conservancy’s action page.

Birds, long revered as the canary in the coal mine, are chiding us to make some big changes this year. We must work together as fellow inhabitants of this incredible planet to preserve its beauty. There are simply too many of us now for anyone to luxuriate in blissful naivete. The scientists have spoken. The canaries have sung.

Let’s be better humans this year, so that we may never hear the swan song of our canary.

There’s a lot going on in the woods,

Blake

At Rushton we do as the birds do and follow their seasons. Each season is unique in its own way, so when we look at the data, we look at each season independently.

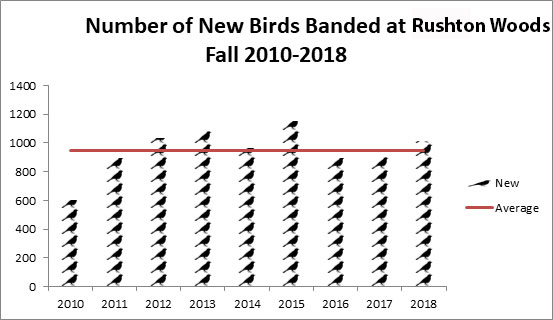

This fall we seem to be catching more birds than we have in the past. This does not contradict the recent reports of bird declines, it simply shows that during this small window of bird migration, over the short time span of 10 years, this is the most we have captured. It’s too soon to know why there are more birds this year; maybe the habitat is just right this year. We changed the habitat slightly by increasing the shrub scrub due to a slightly altered mowing regime. We have also been able to band a little more this fall than in previous years, due to favorable weather. It could also be that we happen to be catching good migration weather, the best winds and on the right days. We have a set schedule of banding the same three days each week, but the birds travel when the weather is right, no matter what day!

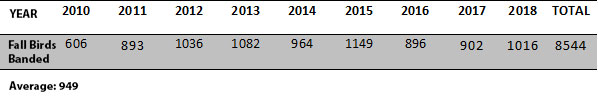

A summary of 9 years of fall migration banding at Rushton:

We typically band from the last week in August until the first week in November, three days a week when conditions allow.

This year on October 10th we caught and banded our 1000th bird (a Black-throated Blue Warbler), at about halfway through the season, already surpassing our average total over the last nine years. Noting this great year, we hope this can become a tradition!

Our lowest year is likely due to fewer hours spent catching birds, more fairly, our lowest catch has been 893 birds and our highest in the last nine years was 1082 birds in 2013.

Looking forward, our winter residents and second most common bird of the fall season, the White-throated Sparrow, has yet to arrive, along with our tiniest fall migrant, the Ruby-crowned Kinglet, which combined, average another 200-300 birds, we can only begin to speculate how many birds we will total by November!

Table 1. Number of birds captured per year during fall migration.

By Blake Goll

Rushton Woods Preserve is a place where people gather in celebration of abundance. Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) members gather for their share of the soil’s bounty each week, and myriad groups from the community, schools, and universities gather at the songbird banding station to witness the bounty of the sky. Much like the agricultural harvest, our bird catch follows seasonal patterns that can help a visitor (or bird bander) develop a deep connection to the rhythm set forth by Earth’s 23.5 degree tilt.

As this was my first year participating in the Rushton Farm CSA, I noticed some interesting correlations between the harvest and the catch. My favorite crisp spring vegetables like kale, radishes, turnips, broccoli, leeks, and little gem lettuces have all made an encore appearance now that the cool fall weather is here. These I liken to our butterflies of the bird world, the “special” warblers, that we can only expect to see during spring and fall migration: Black-throated Blue Warblers, Chestnut-sided Warblers, Magnolia Warblers, Northern Parulas, Black-and-white Warblers, and American Redstarts.

Throughout the summer, I was overwhelmed with tomatoes and zucchini. These prolific crops mirror our common birds that breed at Rushton all summer long like Gray Catbirds and Common Yellowthroats. Catbirds are a bander’s tomatoes making up the bulk of our catch August through September; they even ironically dwindled in numbers at about the same time as the tomato harvest finally ended a couple of weeks ago. And just like the tomatoes, we miss them when they’re gone.

Now CSA members are enjoying the hardy winter produce like squash and sweet potatoes, while our avifauna has shifted to tough winter birds from the north like White-throated Sparrows, kinglets, and Hermit Thrush.

Recent highlights include a young male Rose-breasted Grosbeak on October 10th, our third Yellow-breasted Chat on October 1st (thanks to our new reduced mowing regime), a couple of young female Sharp-shinned Hawks in September, and a young male Scarlet Tanager on September 23rd.

Black-throated Blue Warbler numbers are back up this year from our previous year’s alarming slump. One little female got our silverware on October 1st and decadently dined for five days, increasing her body weight by 22%. A handsome male Black-throated Blue checked in on October 10th as our one-thousandth bird of the season, making this fall our most productive yet by almost double our past records.

This local boom may seem peculiar in the wake of the recent article in Science, citing the devastating loss of 3 billion birds in the past 50 years as a result of habitat loss, pesticides, climate change, and other human threats. However, the majority of our birds are hatch year birds that have yet to complete the most perilous journey of their lives: their first migration in the Anthropocene. Thank goodness we can offer them temporary sanctuary within a community of people who care about open space and the abundance it supports.

There’s a lot going on in the woods,

Blake

925 Providence Road

Newtown Square, PA 19073

(610) 353-2562

land@wctrust.org