By Alison Fetterman, Bird Conservation Associate & Northeast Motus Project Manager and Blake Goll, Education Programs Manager

In April 2021, the WCT bird banding crew members emerged from their winter hibernation and gathered at Rushton Woods Banding Station (RWBS) to begin their 11th year of Monitoring Avian Productivity and Survivorship (MAPS) and their 12th year of spring and fall migration. It was clear that the birds had continued living their celestial lives, lives that were intricately synchronized with the steady rhythms of nature millions of years before we showed up.

THE PEOPLE | Bird banding occurs under the supervision of four WCT staff who are federally licensed by the Bird Banding Laboratory. We regularly train volunteers who are essential to the successful operation of the banding station. In 2021, we were grateful for all our volunteers, but especially our regular helpers: Katie Hogue, Kelly Johnson, Molly Love, Kaitlin Muchio, Edwin Shafer, Jess Shahan, Victoria Sindlinger, Kirsten Snyder, and Claudia Winter. We were also lucky to host a guest bander this year: Holly Garrod. Holly joined as a migratory bander, stopping over for the fall to lend us her expert banding skills before her reverse migration to study birds in the tropics on their breeding grounds.

Other guests to RWBS included staff from the Pennsylvania Game Commission and BirdsCaribbean, with whom we continue to collaborate for a greater conservation impact. We also welcomed U.S. Representative Chrissy Houlahan for a visit in April.

Photo by Jennifer Mathes.

THE MARVELS OF MIGRATION | A small songbird weighing just a little more than a quarter may spend 30% of its year in migration, traveling to and from the exact breeding and wintering locations as the year before. Each spring, an estimated three billion North American migratory birds traverse distances of over 2,000 miles from the tropical wintering grounds of South America to the critical boreal forest “nursery” of Canada — most of them putting in the mileage by night, navigating by starlight and Earth’s magnetic field. This anomalous strategy allows foraging by day along the way, which is vital especially for smaller birds that can only carry so much fuel in the form of fat reserves.

In fact, for most songbirds, 70% of migration is spent feeding and resting in “stopover habitat,” or pit stops, rather than in sustained directional flight. Consequently, understanding how birds use stopover habitat during migration has become just as important to ornithologists as identifying breeding or wintering habitat. This is just one of the reasons why we began banding at Rushton Woods Preserve and Farm 12 years ago. Never was the stopover value of our nature preserve better elucidated than on the morning of May 4, 2021, or as we call it: “The Spring Fallout.”

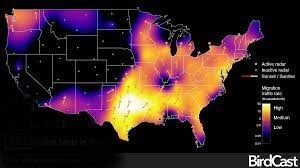

THE SPRING FALLOUT | Bleary-eyed banders arrived to the hedgerows in the blue civil twilight before dawn, expecting a good catch based on the southerly winds from the previous night. As the nets were opened, the vegetation around us came alive with the whispered din of hundreds of excited bird voices chirping about their recent arrival. The low chattering exploded into full song at daybreak, and it was as if we had just entered an aviary with the roar of hundreds of birds representing dozens of different species reverberating through the shrubs and vines. “It’s birdy as heck out here today,” Blake noted, now wide-eyed, as we convened at the banding table to anticipate the first net check.

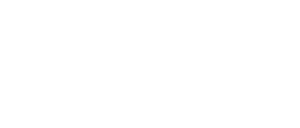

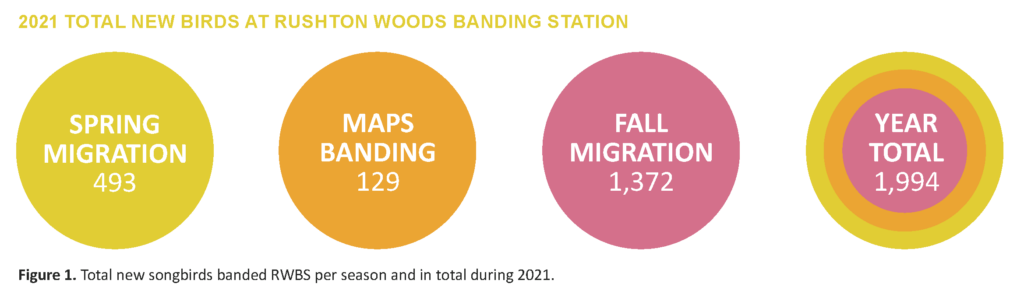

Favorable migration conditions the previous night (Fig. 2), combined with pre-dawn storms and heavy fog presented fallout conditions, a phenomenon where birds cannot continue to their destination because of the energy required to fly through severe weather. This resulted in many travelers honing in on the closest suitable stopover sanctuary. The “good catch” we expected became our best catch ever; our skilled team of bird banders, volunteers, and visitors from the PA Game Commission safely processed and released 180 indviduals — three times our normal catch (Fig. 3).

The avian cast included our first Brewster’s Warbler (defined as a hybrid of the Blue-winged Warbler and the near threatened Golden-winged Warbler) along with a dazzling 25 other species including: Magnolia Warbler, American Redstart, Ovenbird, Blue-winged Warbler, Common Yellowthroat, Northern Waterthrush, Black-throated Blue Warbler, Black-and-white Warbler, Yellow-rumped Warbler, Wood Thrush, Veery, White-eyed Vireo, Eastern Towhee, Gray Catbird, American Goldfinch, Swamp Sparrow, White-throated Sparrow,and White-crowned Sparrow!

Photo by Blake Goll/Staff.

A SUMMER BREEDING RECORD | After the exhilaration of tracking spring migration in the hedgerows and thickets adjacent to the Rushton Farm, the banders moved to the interior woodlands of Rushton Woods Preserve to monitor our breeding birds for the Institute for Bird Populations’ nation-wide study called MAPS (Monitoring Avian Productivity and Survivorship). For eight weeks in the summer, we sizzled beneath the cathedral-like canopy of the royal beeches and tulip poplars and used our mist nets to capture a snapshot of the nesting activity of Rushton Woods. Banding fresh, fuzzy babies just out of their nests is usually reward enough, but last summer we also had the humbling thrill of catching up with a “veery” old friend.

“It’s he!” Alison exclaimed into the data book after Blake routinely read off the nine-digit band number of a recaptured Veery. It was the same Veery we had caught the year before and several years before that; he was first banded in 2011 — our inaugural MAPS year — when we proclaimed him to be at least two years old based on our feather and molt analysis. That makes him at least 12 years old as of summer of 2021 and our oldest banded bird for the station! To put that age in perspective, according to the Bird Banding Lab, the oldest recorded Veery is 13.

The Veery is a long-distance migrating, neotropical thrush, overwintering in central and southern Brazil and capable of flying 160 miles in one night. How awe-inspiring that our old Veery accomplished this feat a dozen times, triumphantly returning each summer to fill the emerald understory of Rushton with his ethereal song. This longevity record is a testament to the importance of preserving land for wild creatures. When you consider what these migratory birds must face on their journeys — habitat loss and destruction by humans, city lights and buildings, climate change, weather, pesticides, open oil pits, natural predators, and cats — it is miraculous that a bird can persist on such a knife’s edge.

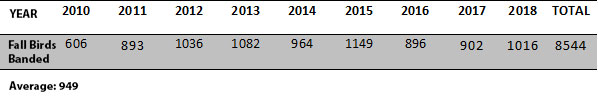

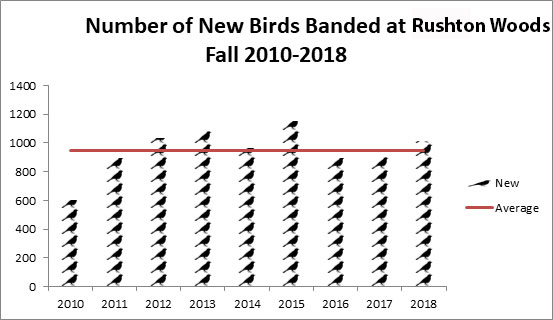

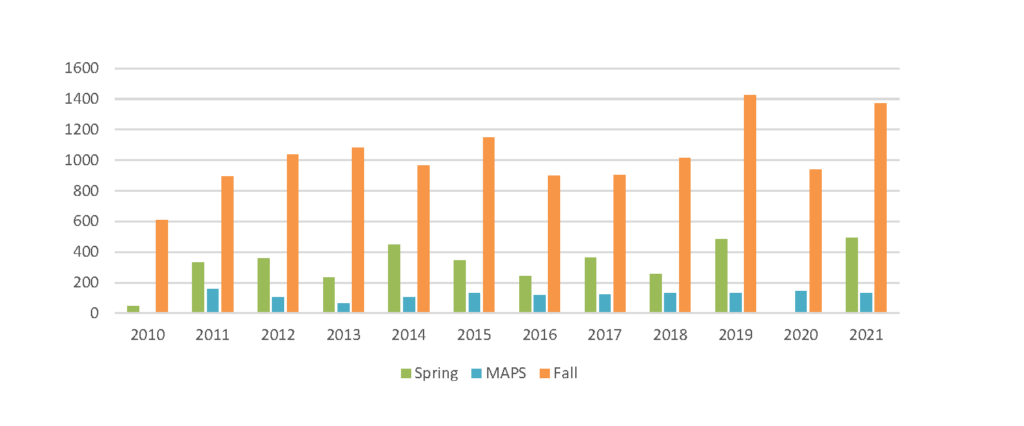

AUTUMN’S BOUNTY | Fall brought Rushton banders back out to the migration station in the relatively open hedgerows where young birds hatched in the dark woods to find a more forgiving landscape for learning how to survive, and where migrants discovered an abundance of insect and berry forage to fuel their southbound journeys. Fall of 2021 turned out to be our second best with 1,372 new birds banded in addition to 174 recaptures of a total diversity of 61 species; for comparison, fall of 2019 brought 1,427 new birds. Gray Catbirds — familiar and endearing garden birds related to mockingbirds — had a record year, comprising 42% of our total new birds! The majority of these were fresh youngsters hatched that summer; this annual recruitment of new birds into the population is the reason why we see a species-wide increase in abundance during the fall season relative to spring; for comparison, spring 2021 totaled 493 new birds (Fig. 4.).

The fall banding season is also much longer than spring, with birds taking a more leisurely voyage in the absence of the pressure of mating. Last September brought beauties like the chartreuse Chestnut-sided Warbler, the dashing Black-throated Green Warbler, and the elusive Connecticut Warbler.

September also produced our 102nd species for the station, a Cooper’s Hawk, that was ceremoniously banded by expert raptor bander and renowned naturalist and author, Scott Weidensaul. Scott happened to be visiting for a talk he was to give that evening about the Willistown Conservation Trust’s role in Motus Wildlife Tracking and his most recent book: “A World on the Wing: The Global Odyssey of Migratory Birds.” After the raptorial hawk was gently banded and processed, it was temporarily excused from the net premises for the safety of the rest of our songbirds.

Though 75% of the songbirds we catch are only caught once, there is immense value in the few birds we see more than once. For example, we caught a young Worm-eating Warbler on September 8 and again on September 30. This bird likely hatched late summer on a nearby wooded hillside, then dispersed to the Rushton shrublands, illustrating the importance of shrub habitat — including those typically associated with forests — for young birds learning how to make a living before their first migration. We also caught other songbirds stopping over, like the hatch-year female American Redstart who gained 27% of her body weight in just 10 days; that’s the equivalent of a 145 pound human gaining almost 40 pounds in a little over a week! Birds gain weight in this rapid manner only to prepare for long overnight flights. Studying the rate of weight gain through recaptures such as these can help shed light on the quality of stopover habitat in terms of supplying adequate forage for migrants.

Finally, one of the last days of the season produced our fourth ever American Woodcock! These marvelously camouflaged earthworm-eaters prefer early successional woodlots next to open fields — like those found at Rushton — where the males can perform their esoteric sky dances, electrifying the dusk and moonlit skies of spring with their wing twittering and chirping spiral descents.

Photo by Blake Goll/Staff.

BIRD BANDING AND LAND CONSERVATION | When all is said and done, we banded nearly 2,000 birds in 2021, between spring migration, summer MAPS, and fall migration. It was a wild year that included fallouts, two new species for the station, discovering a bird that was with us since our very first year, hosting hundreds of visitors including special guests, and training many students and colleagues. Through banding we continue to learn information about species abundance and diversity, individual longevity and site fidelity, and how birds are using our conserved land throughout their annual cycle.

Our banding station’s high catch rates — or “birdiness” — combined with the unique setting on a regenerative farm within a greater nature preserve shows the world that people and wildlife can coexist in harmony. On a broader scale, as Rushton Woods becomes inreasingly surrounded by human development, our continuous banding efforts may be illuminating the Preserve as a critical island habitat for birds traveling through, wintering, or breeding in the region.

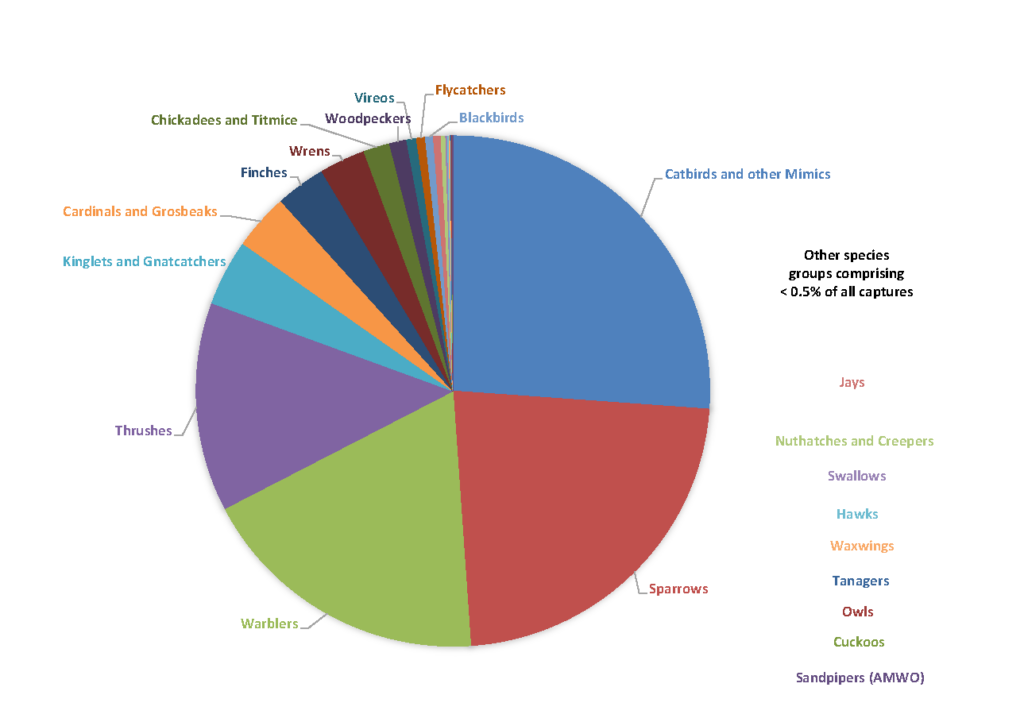

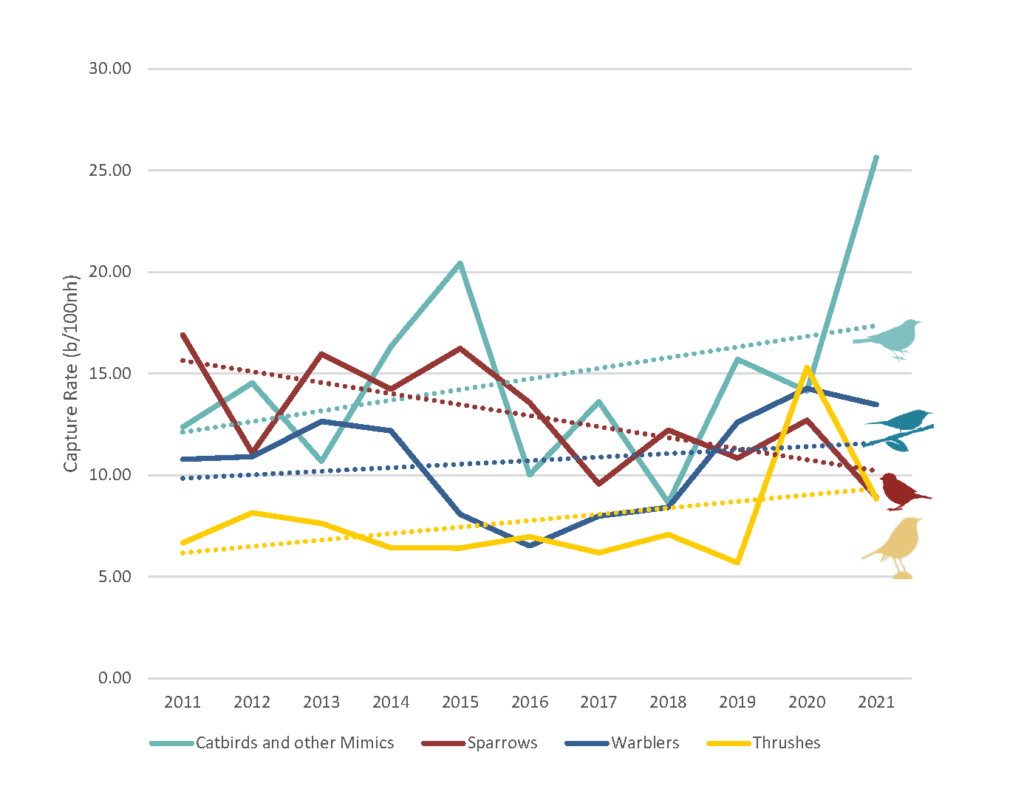

With more than 17,000 birds banded over the last 12 years, it can be useful to look more broadly at species groups and their changes over time. Birds of species groups have many similarities, including diet and foraging habits. For example, we typically capture over 200 warblers of different species each year. Since most warblers are tree top dwelling, insect gleaners, if we group them together, we may gain a better understanding of habitat priority needs at Rushton. Our captures are overwhelmingly dominated by Catbirds, Sparrows, Warblers, and Thrushes (Fig. 5). And when we look at the capture rates over time, we can see that all are increasing except for Sparrows (Fig 6).

The gravity of the state of birds today runs the risk of being lost on the reader through an auspicious annual banding report such as this. It must be noted that in less than one human lifetime, North American bird populations have plummeted by 30% with no ecosystem spared; that’s three billion, or one in four birds gone since 1970, largely due to human actions. So while we recover from our world being briefly disrupted by the uncertainty of a pandemic, we must learn to minimize our disruption of the natural systems to which we are inextricably linked.

You can find the full Rushton Woods Banding Station Annual Songbird Banding Report, as well as a full list of all species we’ve banded each year since 2010, on our website.

One thing’s for certain: the wild birds at Rushton will always be welcome, where the rhythm of winged creatures reigns.

RESOURCES

Institute for Bird Populations

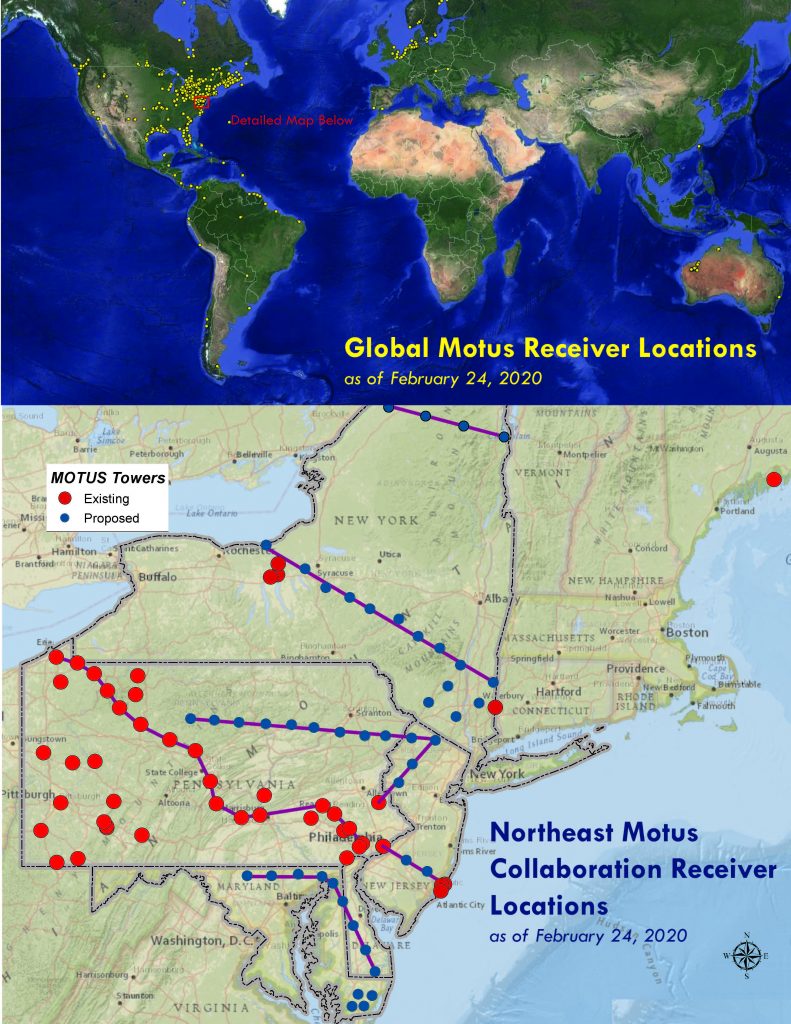

Northeast Motus Collaboration

Rushton Woods Banding Station Annual Songbird Banding Report

Species Seen List