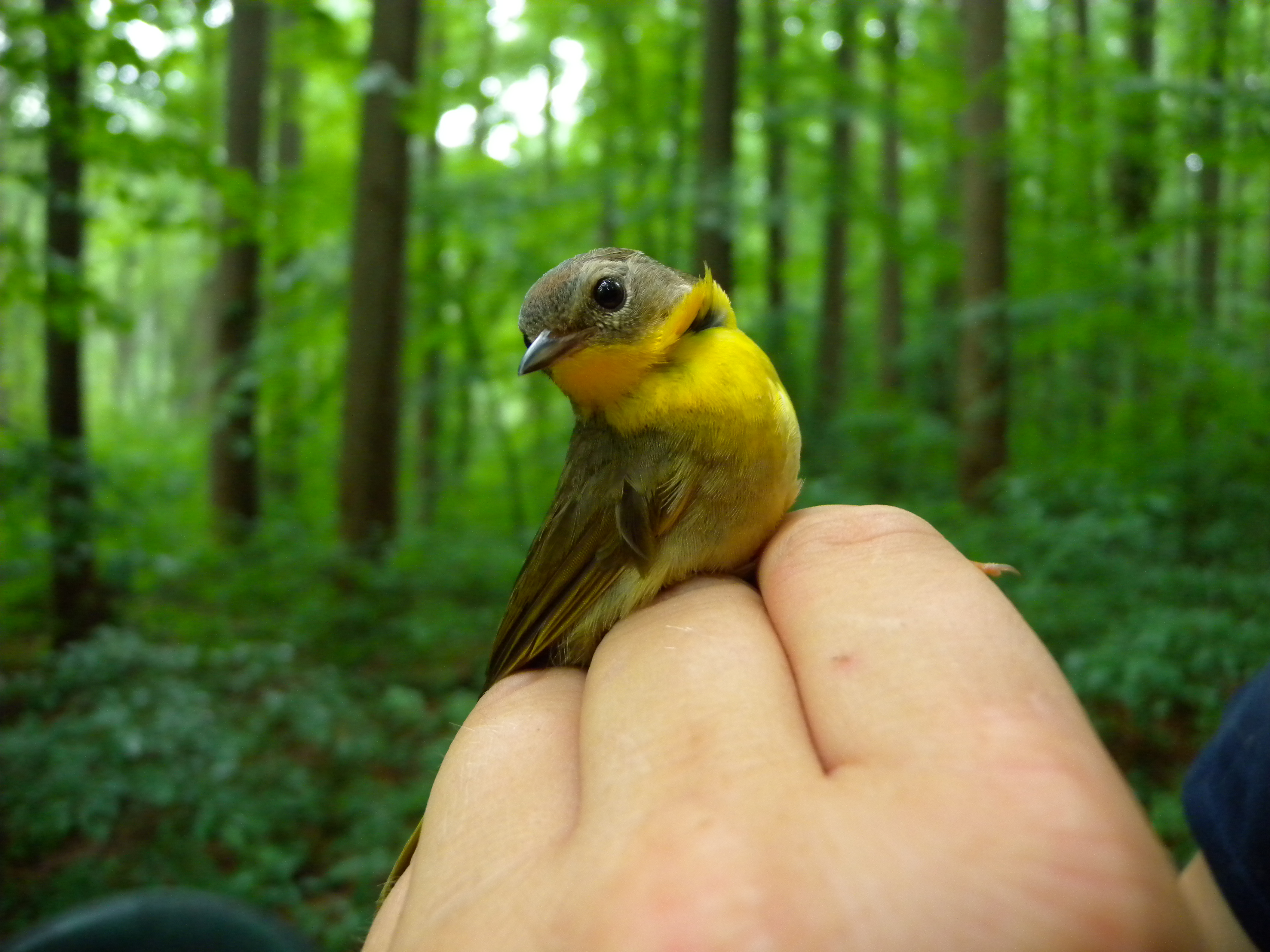

Another dreary, drippy morning on Tuesday surprisingly produced a season record of 54 birds spanning a dazzling 20 species. Highlights included Gray-cheeked Thrushes, another prized Connecticut Warbler, the first Yellow-rumped Warbler of the season, and an increase in numbers of individuals of several species as compared to previous years—including Black-throated Blue Warblers, Indigo Buntings, and Eastern Towhees. The grande finale was a glorious Yellow-breasted Chat, the second ever for Rushton!