The following is an excerpt taken this year from my journal, “Meadow Walking,” an attempt to document the delights of our native wildflower meadow through the seasons. This meadow is located in front of the Willistown Conservation Trust office on Providence Road in Newtown Square and has been flourishing in place of a traditional lawn for nine years now.

Early September in the wildflower meadow is absolutely spectacular. Many of the flowers are admittedly past their peak, but their charming seed pods serve to add more texture to the intricate palette and only make the late blooming flowers that much more vibrant. There is a palpable heartbeat here…

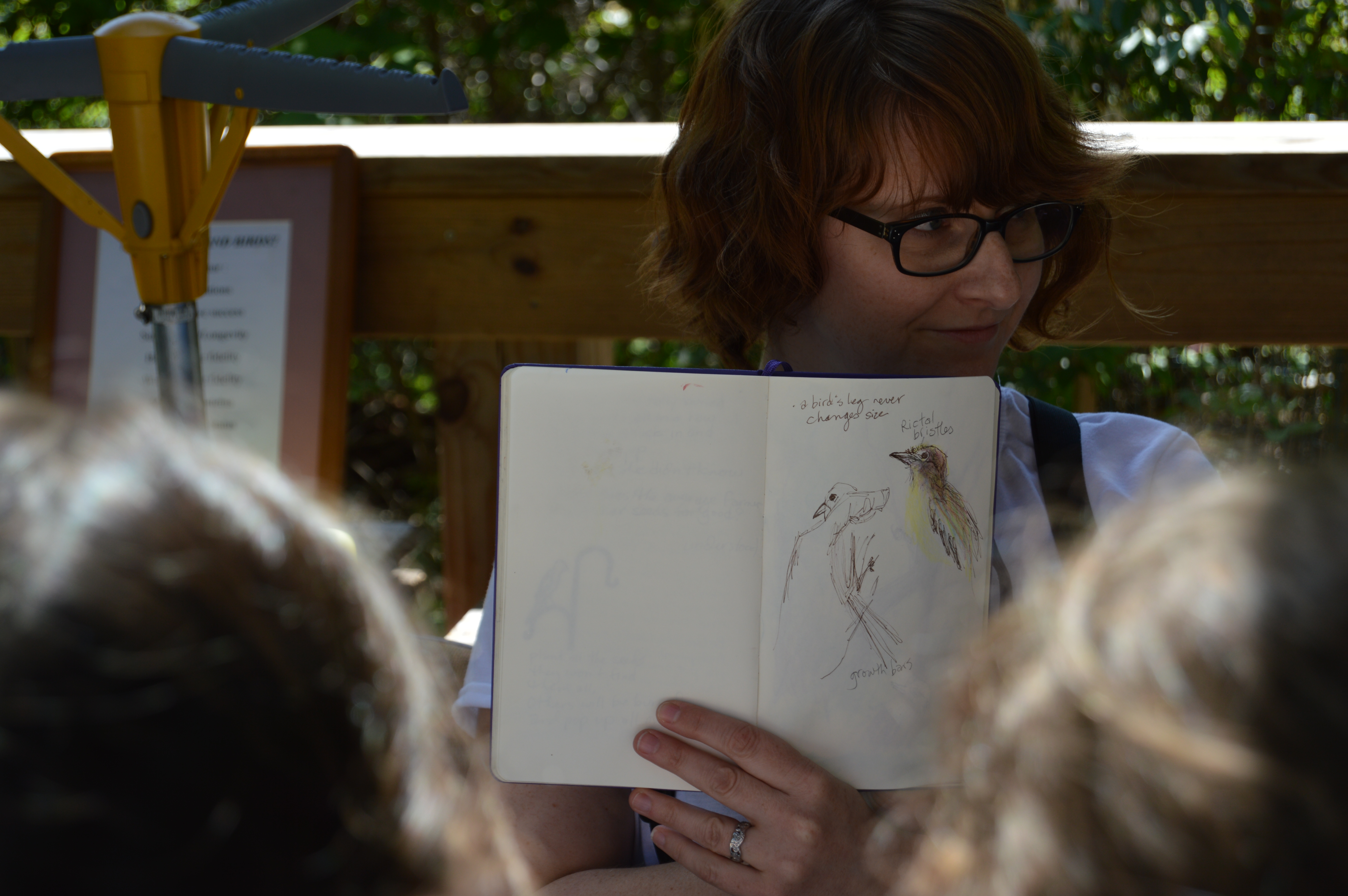

A flock of fifteen goldfinches frolics across the sky from one patch of seed heads to the next. First to the Virginia cup plant, then the False sunflowers. Next the thistle and back to the cup plants for a drink. Meanwhile, two young mockingbirds awkwardly flash their wing patches in the trails, practicing stirring up insects to eat. They notice me and dive into the swath of Virginia cup plant where they suspiciously eye me up as I attempt to catch photos of the shy goldfinches. A sporty chipping sparrow runs across the grass trail in front of me like a mouse diving into the meadow. I hear young blue jays begging for food and a teenage , “gray headed” Red-bellied woodpecker tap tap tapping on the walnut tree. Honeybees lazily buzz from the delicate white sprays of boneset to the mustard yellow of the grass-leaved goldenrod. A black swallowtail flits from one deep purple spray of New York ironweed to the next. I marvel at how the autumnal violet of the ironweed complements the harvest yellow of the goldenrod in this beautiful meadow of life.

You cannot stand amid this cathartic jubilee without absorbing the energy that abounds in the grasses, the flowers, the birds and the insects. You cannot help but feel rejuvenated as a cool breeze momentarily cuts the summer heat, whispering of the fall to come. Although I didn’t quite get that photograph I was looking for, I received far more than I sought.

As I head back up the path, those stealthy goldfinches dodge the yellow leaves that spiral down from blue skies as they continue their methodical wanderings from one corner of the meadow to the next.

As you wander from one chapter of your life to the next, may your pulse echo the rhythm of the meadow. Like the perennials, may your roots reach deep into good soil so you stand strong in the changing winds. May you revel in the clear days but remember the buoyant grace of the goldfinches when those leaves inevitably fall from blue skies. If life doesn’t quite give you what you dreamed of, remember that in nature you often receive far more than you seek— advice from the great John Muir who undoubtedly also sought solace and strength from wildflower meadows.

May your new year be filled with deep breaths, quiet walks in nature, vitality and magic.

Blake

P.S. Be sure to stay tuned in the new year for the summary of this fall’s spectacular banding season, big news for 2017 and more musings from the meadow.