By Sally Ehlers, 2023 Watershed Protection Program Co-op

For over a century, macroinvertebrates have been our partners in understanding the intricacies of stream health, providing us with valuable insights that shape the conservation efforts of our aquatic ecosystems.

Macroinvertebrates are small organisms lacking a backbone that are visible to the naked eye, which inhabit aquatic environments. They form a diverse and abundant group, but their significance extends beyond mere existence – they are crucial to ecosystem function. By converting organic plant matter into animal biomass, these tiny marvels create a foundation that supports the intricate web of life in our streams and lakes. The diet of larval amphibians, fish, other aquatic insects, and birds are all supported by macroinvertebrates.

Macroinvertebrates are also reliable indicators of environmental health in our streams and lakes. Their presence – or absence – illustrates the overall well-being of these water bodies, making them an asset in bioassessments. Their widespread distribution, sensitivity to changes in water quality, and diverse abilities to tolerate environmental stress make them indispensable tools for monitoring and maintaining the health of aquatic ecosystems. These remarkable organisms help us learn about what is happening in our waterways.

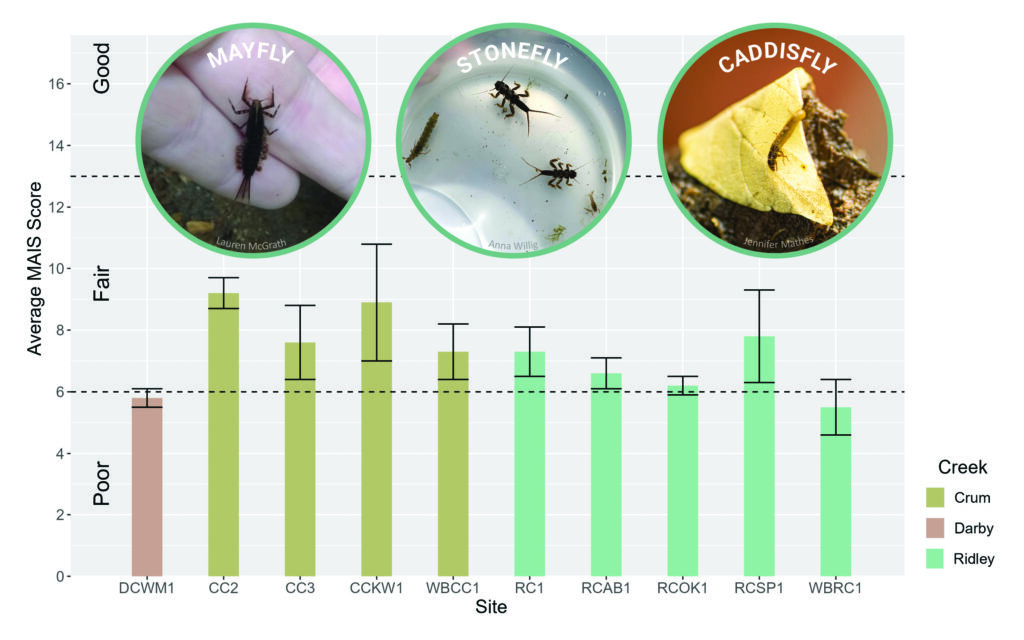

Certain taxa (insect groups) are known to be sensitive to environmental changes and are considered pollution-intolerant. Mayflies are known for their short adult lifespan and are highly sensitive to pollution, making their presence a highly valuable indicator of pristine or recovering water systems. Stoneflies are also sensitive to water quality, especially oxygen levels. Therefore, they are typically found in clear, well-oxygenated streams. Caddisflies are known for their case-making larvae and can tolerate a range of water quality conditions, but some species within this group are also sensitive to pollution.

In addition to these sensitive insects, there exists a cast of pollution-tolerant taxa in these freshwater environments. Some examples that are found in local waterways are midges, worms, and black flies. While not standalone indicators of water quality, their presence and abundance, paired with pollution-sensitive taxa, contribute to a more comprehensive picture of the ecological health of aquatic systems.

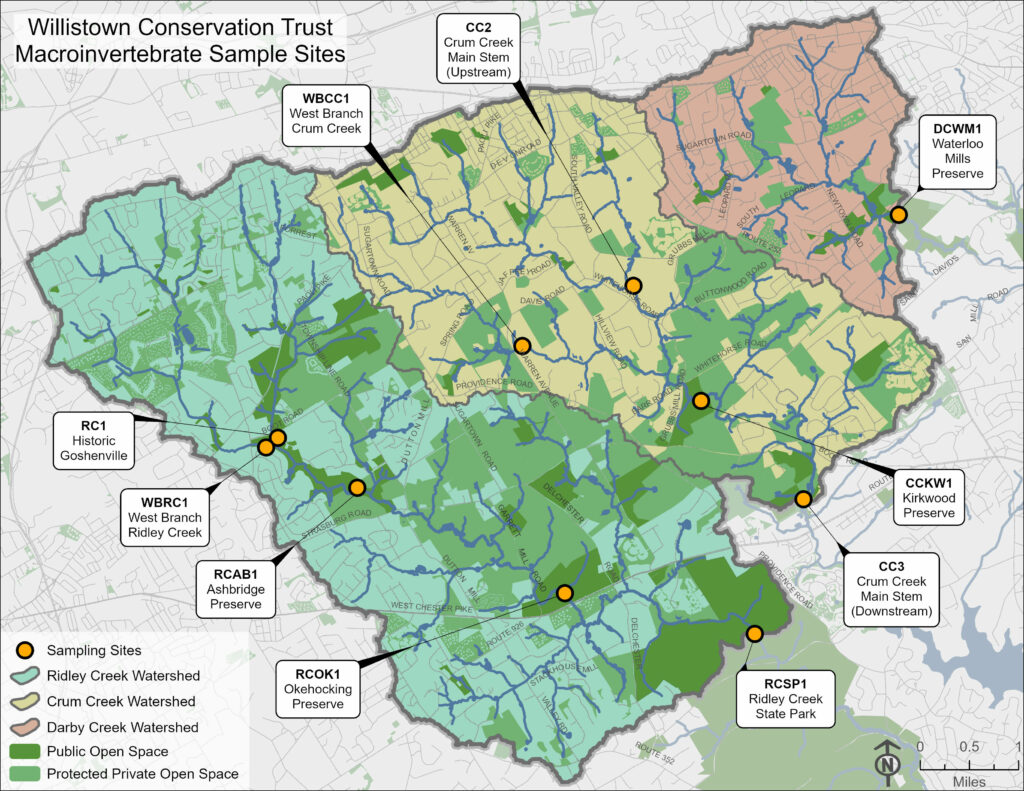

Each spring, the Watershed Team heads out to ten sites in Ridley, Crum, and Darby Creeks to collect macroinvertebrate samples using a Surber sampler (a modified net for collecting insects), a scrub brush, and lots of hard work (Map 1). Since these critters hang out at the stream’s bottom, we scrub rocks, letting the stream flow guide the macroinvertebrates into the net. As a Watershed Protection Program Co-op, I had an amazing time assisting with the 2023 sample collection.

Now, my capstone project involves analyzing the data from past years to turn raw survey data into meaningful results. Macroinvertebrate Aggregated Index for Streams (MAIS) scores were calculated which combine several types of data into a single score that is used to classify stream health as “Good,” “Fair,” or “Poor.” Results suggest that on average, most sites are moderately impacted, with “Fair” health (Figure 1). However, DCWM1 (Darby Creek) and WBRC1 (West Branch Ridley Creek) had low MAIS scores, suggesting that these sites are in “Poor” health.

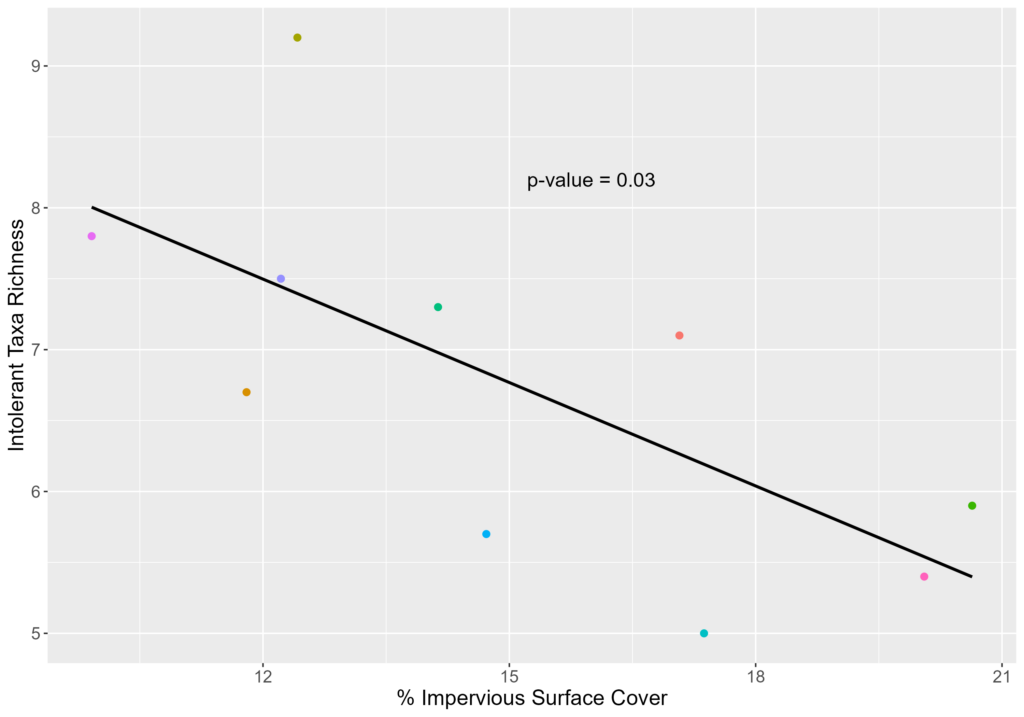

Development on the landscape helps explain why DCWM1 and WBRC1 rank lower in MAIS scores as these sites have 20% impervious surface coverage, the most out of all sample sites. Impervious surface cover refers to structures that are water-resistant such as paved roads, parking lots, and buildings’ roofs. Water cannot penetrate these surfaces and flows directly into waterways, picking up contaminants as it travels. In contrast, forested land allows water to seep into the ground and trees can help reduce the amount of runoff into the stream.

There is a significant negative correlation between percent impervious surface cover and intolerant taxa richness (Figure 2). This means that as impervious surface cover increases with more development, the number of pollution-sensitive macroinvertebrates decreases. Increased impervious surface cover leads to more runoff and contaminants, such as road salts, entering our waterways, and only macroinvertebrates that can withstand these changes can survive. This preliminary data highlights the importance of WCT’s land conservation efforts. Protected open space is critical to keep local streams healthy and macroinvertebrates thriving.

While it will take more sampling years to spot clear trends over time in local streams, the current data from 2018 to 2022 begin to shed a light on the state of these streams from the viewpoint of our macroinvertebrate community, and so far, aligns with existing water chemistry data. Follow along on WCT’s blog to take a deep dive into the data set and learn more about the results of the ongoing macroinvertebrate research effort!

Sally Ehlers | Sally is a senior at Drexel University where she is majoring in Environmental Science with minors in Biology and Writing. Before joining the Watershed Protection Program, she spent six months working at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Fisheries Lab in Highlands, NJ. There, she assisted with two ecotoxicology projects, focusing on the early life stages of local riverine and estuarine fishes. As a Watershed Protection Program Co-op over this past spring & summer, she helped collect water samples, run water quality analyses in the lab, maintain equipment, and practice science communication through WCT’s blog and Instagram stories.