By Lauren McGrath, Director of the Watershed Protection Program, and Susan Lea, Darby and Cobbs Creek Community Science Volunteer

In 1919, naturalist and zoologist Arnold Ortmann, in connection with his taxonomic studies of freshwater mussels (Unionidae), recorded approximately eight species of mussels in Darby Creek. As of a decade ago, surveys of more than sixty stream reaches in Southeastern Pennsylvania yielded only about six relic populations of the eastern elliptio (Elliptio complanata). Freshwater mussels are the most at-risk animal group in the United States due to pollutants and poor water quality, habitat loss, and barriers to host fish. Yet, the eastern elliptio remains a common mussel in the tri-state area and has been previously identified by the Willistown Conservation Trust (WCT) Watershed Protection Program Team within the headwaters of Crum and Ridley Creeks. However, among the local scientific community, it was believed that historic pollutants had eradicated freshwater mussel populations in Darby Creek; discovering a mussel shell was merely an artifact of what once was. That is, until now.

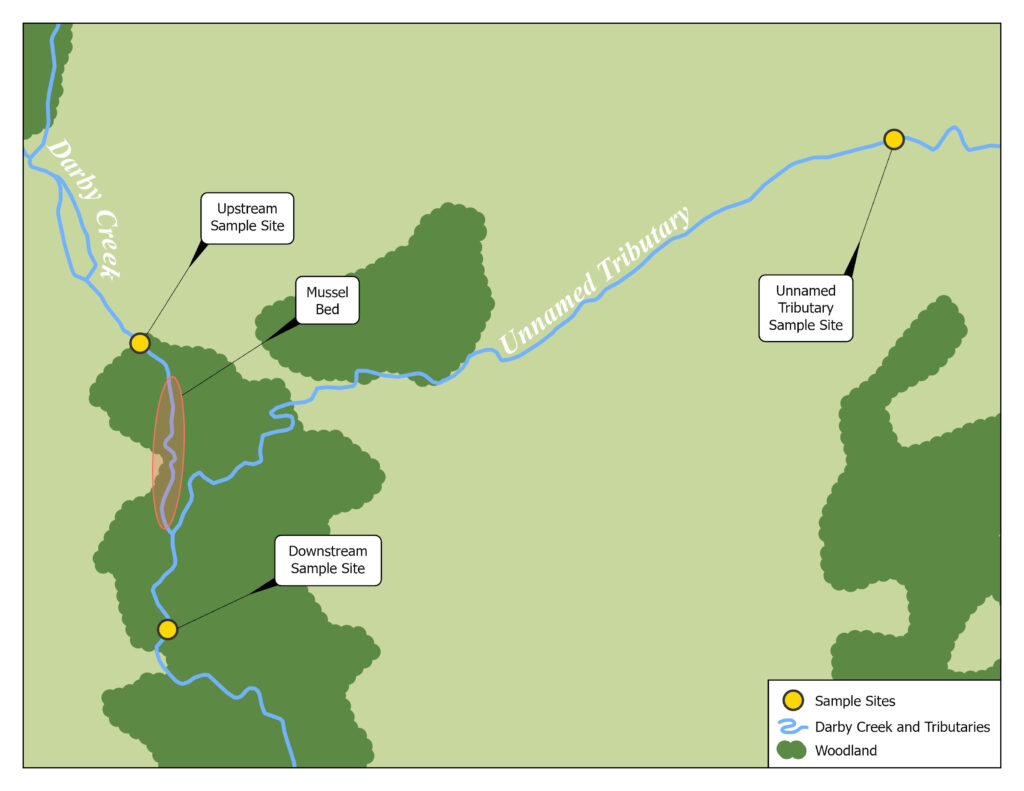

The Darby and Cobbs Creek Community Science Monitoring Program (DCCCS), a collaborative project among WCT, Darby Creek Valley Association (DCVA), and Stroud Water Research Center, was established in the spring of 2021. Since the fall of 2021, a DCCCS volunteer has monitored two sites in the Darby Creek headwaters in Berwyn, about 275 yards apart and bifurcated by an unnamed tributary. After noting several mussel shells in the stream (eastern elliptios can live up to 80 years), the volunteer discovered a small mussel bed of about a dozen live eastern elliptio mussels in 2022. The following summer with the assistance of staff from WCT and DCVA, several more eastern elliptio beds, with mussels numbering over one hundred, were identified between the two sites. Curiously, the mussel beds seemed to stop downstream from where the unnamed tributary entered Darby Creek even though their preferred sandy substrate continued further down the waterway.

Equipped with this discovery, curiosity about the impact of these amazing bivalves on the watershed, and innumerable questions, DCCCS reached out to Dr. Erik Silldorff, Restoration Director & Senior Scientist at Delaware Riverkeeper Network, who agreed to lead the survey effort in Darby Creek to gain a better understanding of the health of this special mussel bed. Dr. Silldorff has years of experience conducting mussel surveys in the Delaware River watershed and was enthusiastic about sharing his knowledge and training a new cohort of mussel advocates on identification and survey techniques.

On a balmy morning in late May, the team of mussel enthusiasts came together: staff from WCT, DCVA, and Brandywine Conservancy; students from Drexel University and Oberlin College, high school students, residents, educators, and township officials eager to learn more about these fascinating stream residents. All gathered together to learn how to discern the difference between common species of mussels based on their shell morphology and to learn more from Dr. Silldorff about the fascinating biology and ecological decline of mussels in the Delaware Watershed.

After two days of careful inspection of the stream bed through goggles and snorkels and using clear-bottomed trays, over 850 mussels were documented in Darby Creek, a population large enough to be a remnant that survived the colonization of North America. The majority of mussels found were eastern elliptio, but to the delight of all, two live Alewife floater mussels (Utterbackiana implicata) were also found in the waterway. Alewife floaters use a broad variety of habitats, including ponds and lakes, as well as streams, rivers, and tidewaters; their presence in Darby Creek suggests that there may be additional populations somewhere upstream.

Truly the most exciting discovery of the survey was two juvenile mussels, less than one inch long, that were found perched on the edge of two separate fish nests. Juvenile mussels bury themselves in the sediment and are difficult to find without the use of specialized survey techniques. Fate and fish worked with the survey team as the nest-building fish had excavated the young mussels in time to be found and documented.

Curiously, there were fewer mussels downstream of the unnamed tributary, and no mussels within the tributary. These observations line up with three years of water quality data collected by DCCCS volunteers at sample sites upstream, on, and downstream of the unnamed tributary (see map). The upstream site has better water quality than the downstream site, and the site on the unnamed tributary has the poorest water quality of all. This suggests water conditions in the unnamed tributary are negatively impacting the mussel population. Further investigation is needed to understand this pattern and ensure this historic mussel population continues to thrive for generations to come.

Freshwater mussels are generally considered inedible, yet they are top-tier bioindicators of water quality, as they are sensitive to pollutants, including road salt, and water temperature. They are also integral to healthy stream ecosystems. Despite Darby Creek’s status as an impaired watershed, the presence of these amazing organisms tells an important story about the resilience of natural systems. However, this resilience cannot be taken for granted, and further research is needed to understand why this population disappears below the unnamed tributary and why there are no additional mussel beds as the stream flows further downstream. Protecting these most delicate and sensitive stream creatures translates into safer, healthier water for all residents who live in and alongside Darby Creek.