By: Lauren McGrath, Director of Watershed Protection Program

For the Watershed Program, it has felt like the September that never ends. A warm, dry autumn has made for great foliage, but there are growing concerns about the impact of a fall with no rain. Fall of 2024 has been notably dry, with Philadelphia having the longest dry period since weather record-keeping began 153 years ago – an unbelievable 42 days with no rain. For the first time in the region, there was no rain in October, and temperatures were unseasonably warm, which can cause more water to leave the soil. While the dry period ended with rain on November 8, Chester County is still facing drought conditions expected to persist throughout the month of November.

With this record-breaking dry spell, what is the impact on local streams?

Unsurprisingly, the lack of rain has a significant impact on the health of local waterways. As rain continues to be elusive in the region, the amount of flowing water in many waterways continues to drop causing physical changes to stream habitat. Low flow conditions can cause dramatic changes to resource availability. The resulting changes to the flow patterns and currents can cause sections of normally flowing streams to become isolated and turn into pools, trapping wildlife in stagnant water. Decreased water levels also means that there is just less space for wildlife in the stream, causing crowding and more competition for fewer resources. In some cases, small streams can dry up entirely. This dramatic loss of habitat has been documented at one site in the Darby Creek Watershed already during this historic drought.

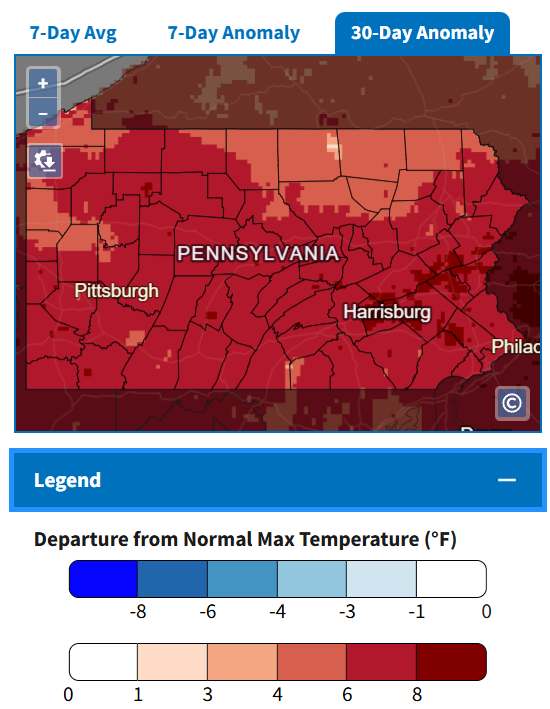

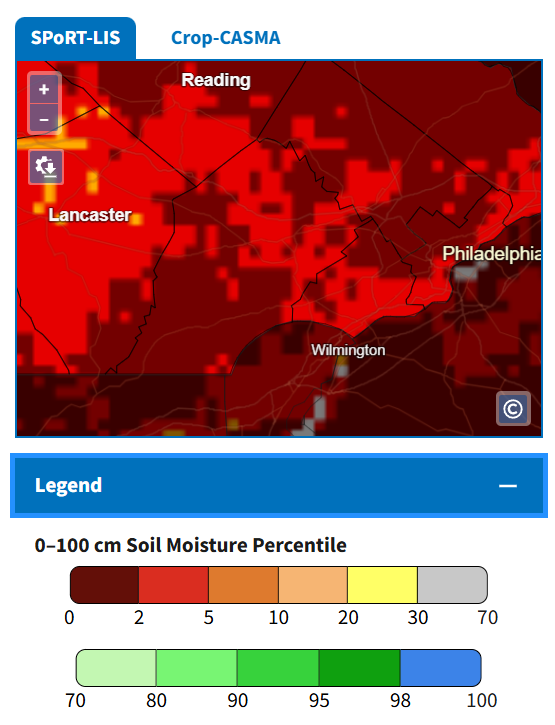

Droughts also cause changes in water chemistry. With flow patterns changing, the availability of oxygen can be reduced, with slow-moving water failing to distribute dissolved oxygen at levels to support sensitive stream life. This can create life threatening conditions for sensitive stream life. Changes in flow also influence chloride levels. While some chloride is present in the geology of Chester and Delaware Counties, the majority of chloride is introduced into local watersheds through the application of road salts (usually sodium chloride, NaCl) to melt snow and ice in the winter. As the snow and ice melt, the salt flushes into local waterways. In areas where salt is applied frequently and in abundance, the chloride can build up in the soils, leading to salty groundwater and high levels of chloride year round – instead of just after winter storms. Chloride, including that from road salt, is known to be harmful to sensitive fish and invertebrates in freshwater systems.When salt buildup in soils meets drought conditions, it leads to salty streams. Less rainfall, (or in the case of October 2024 no rainfall), leads to little to no dilution of groundwater entering the stream, increasing the concentration of chloride in local waterways. When these dry conditions are paired with unseasonably warm temperatures (Fig. 1), it is a recipe for rapid evaporation of surface waters (Fig. 2). Evaporation leaves chloride behind, causing even higher concentrations of chloride ions. During a severe drought, stream systems are almost entirely fed by groundwater, which means the potential for higher concentrations of chloride ions.

Salty streams become extremely dangerous for sensitive aquatic life as temperatures rise, with both chloride and warm streams causing stressful conditions for stream residents. With unseasonably warm days still to come in November and no rain in the forecast, there is likely to be a long-term impact on the health of local streams. Warm air temperatures also mean less oxygen available in the water, increasing the risk factor for aquatic life.

While the drought is not necessarily caused exclusively by climate change, it is being made more severe by the warm temperatures, especially in the fall months of September and October. Models predict that these months will continue to warm at a faster rate than the rest of the year and rainfall events will be extreme, with more rain falling in shorter periods of time. The Watershed Team monitors water temperature, conductivity, and chloride levels at ten sites across Ridley, Crum, and Darby Creeks as well as an additional 34 sites throughout the Darby and Cobbs watershed through the Darby & Cobbs Creek Community Science Monitoring Program on a monthly basis. As data analysis takes place, we will share updates on what we are learning and how you can help stream health.