By Pam Kosty

Most of us know: plastic, especially single-use plastic, is a big problem in our world today. And as one person faced with an avalanche of “convenience” plastics that make it into my life every day — cups and bottles, straws and boxes, and wrapping and netting around almost everything I set out to buy — I can feel overwhelmed.

Photo Caption: Left to right, Pat Jordan and Pam Kosty, EJ Team members, staff a signup table at Main Line Unitarian Church inviting people to join the regional Plastic Free July Challenge. A small box features plastic-eating worms, part of a science experiment. The worms did eat a bit of plastic before dying, but they appear not to be a complete solution to the single-use plastic crisis!

This year, about 380 million metric tons of plastic — about the weight of all of humanity living today — will be created from liquid fossil fuels and thousands of chemical additives, many of them known carcinogens. Much of this new plastic will enjoy a single use (that plastic bottle of water? That vegetable wrapped in cellophane at the grocery store?) before heading to a landfill (less than 10% is recycled), where it will not break down for hundreds of years or longer. Or, as I’ve learned as a volunteer Citizen Scientist understanding more about our local waterways, the plastics will end up in our water supply. The health consequences of this plastic are staggering, to humans and to all of life on earth.

That’s why, when I heard about Plastic Free July — a challenge to individuals to cut back or eliminate single-use plastics for one month — I took note. Founded in 2011 by a small group of Australians, Plastic Free July has grown annually. Last year, more than 140 million people took the challenge.

I am the co-chair of an Environmental Justice team at Main Line Unitarian Church, and I asked team members there if they would be interested in promoting and taking the challenge. The answer, with some trepidation, was yes — but how do we make it social, and local, and fun? Cutting back, yet alone cutting out single-use plastics is tough. Our society is steeped in a single-use plastics convenience culture. Where can people go to share their successes, vent their frustrations, and get advice?

So we started a regional Plastic Free July website and forum, open to all, designed to be a simple space where folks can “sign on” to take the July challenge, share great resources on the forum, and know that they have a regional community that supports them. (You can join it too. Please do!)

Through PA Interfaith Power and Light, my own Unitarian Universalist environmental group connections, and other faith-based groups concerned about climate change and the environment, we’ve created a coalition of so far 10 faith communities all doing what they can to get the word out, and get congregants to sign up, to reduce their plastic use.

Individually, the problem is overwhelming. But in community, there is hope and strength. As we create a community on our regional website, we ask people to do two small things: 1. Invite one friend to join you (and just like that, you’ve doubled your impact). 2. Use this experience to engage with at least one pollution-producing company (a store with lots of plastic packaging, a company that sells their drinks in plastic bottles), asking that they reduce their reliance on single-use plastics.

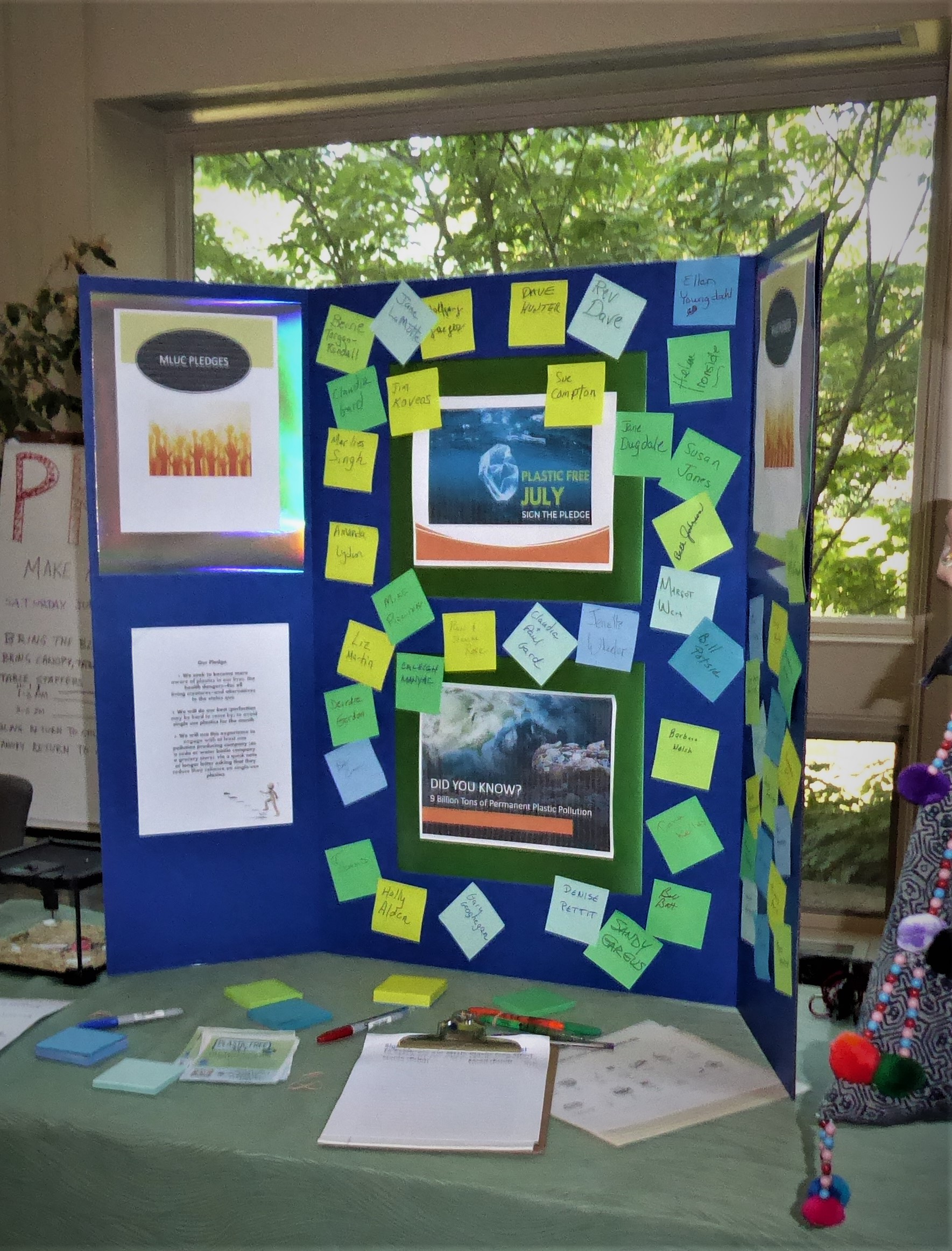

Photo Caption: Members and guests at Main Line Unitarian Church are encouraged to sign the regional challenge, and get “on board” to reduce and refuse more single-use plastics. Signers are added to the board via post-it notes. Each week, the community grows!

Since the forum went up in early June, folks have been sharing their favorite tips on how to avoid buying everything wrapped in plastic. A group of us took a field trip Narberth, PA to enjoy lunch together and visit SHIFT, a new, women-run “refillery” and community center focused on ways to eliminate single-use plastics and reduce our carbon footprint. The owners shared their story and inspired us to do a little more with a little less.

Though single-use plastics didn’t even exist until the 1950s, plastic pollution today is a daunting problem. I believe that there can be a shift — if we choose to make one. And because we are social beings, it’s more fun to make that sustainability shift with friends. I like to remember the words of anthropologist Margaret Mead: “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful committed individuals can change the world. In fact, it’s the only thing that ever has.”