How the American Beaver Mitigates Drought Impact

By: Sarah Barker

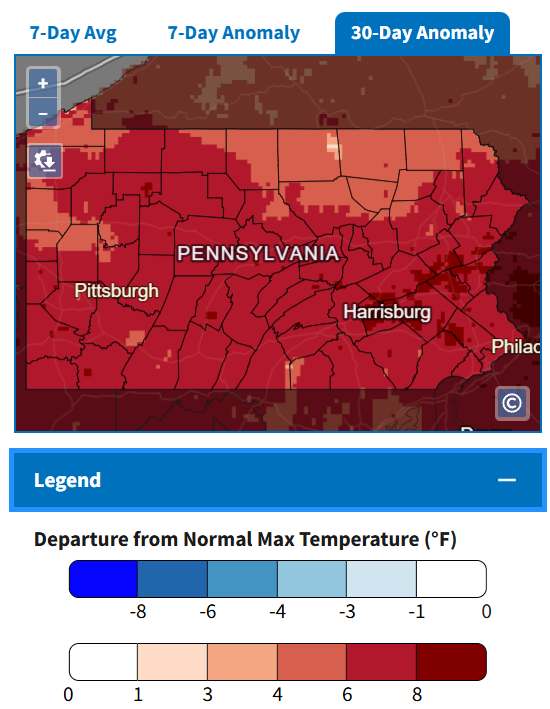

As we near the end of what is shaping up to be the hottest year in documented history, one of nature’s most impactful (and adorable) engineers is working hard to keep our ecosystems green. The American beaver (Castor canadensis) may be our saving grace as drought and wildfires become more frequent due to the growing climate crisis. Research conducted over the past few decades reveals the profound positive influence beavers have on their habitats across the country, even in extreme conditions. Whether they are meandering through Pennsylvania temperate forests (Margolis et al., 2001), arid landscapes in Nevada (Fairfax & Small, 2018), or habitats west of the Rockies (Fairfax & Whittle, 2020), the importance of beaver activity in building environmental resilience cannot be ignored.

Beavers are herbivorous and semiaquatic mammals, they eat woody vegetation, fruits, and herbaceous plants like skunk cabbage or sedges, and they live both on land and in the water. Beavers are renowned in the animal kingdom for their impressive constructions made from chewed trees, shrubs, and miscellaneous found materials. While large dams may be their calling card, they also build homes called lodges into the banks of water bodies, food caches to sustain them through the winter, and trails and canals for transporting food and building materials.

Before the European settlement of North America, beavers could be found in nearly every freshwater body in the country. As colonization spread from coast to coast, beaver populations dwindled as they were hunted to near extinction due to their value in the fur trade, significantly altering ecosystems. Beavers have since reclaimed much of their historical range thanks to nationwide conservation and reintroduction efforts, allowing these master craftsmen to once again shape the landscape. Evidence suggests we all stand to benefit greatly from their return.

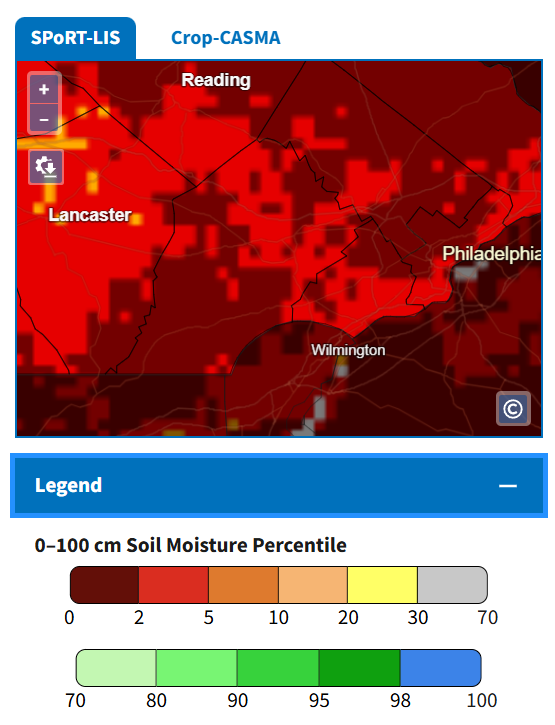

Beaver dams can completely change an ecosystem: flooding forests, creating ponds, irrigating desiccated soils, and bringing life with each trickle of water. Beaver ponds that form between dams or upstream of a dam slow the rate of flowing water and flood the surrounding watershed area. This allows moisture to permeate more soil as the water level rises. In periods of drought, like we have experienced in PA over the past few months, this increasing water level provides essential hydration for thirsty roots. It also creates important refuges and oases for aquatic and terrestrial wildlife alike; including fish, frogs, turtles, raccoons, mink, deer, and more. Birds too can be observed bathing in beaver ponds and hunting for fish or insects.

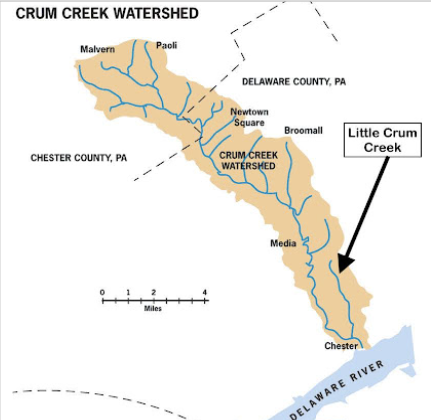

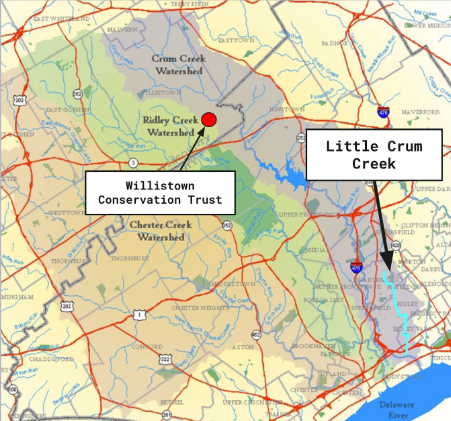

By building successive dams in the same stretch of a river or stream, beavers can sustain or create wetlands even during intense drought; a behavior we have observed at WCT’s Ashbridge Preserve! Beavers are slow and clumsy on land but are graceful swimmers. Therefore, higher water levels provide easier access to food and less risk of predation. Beavers are also fantastic stewards! They chew down local invasive plants like privet and grapevine for their dams while selectively foraging twigs from natives like black willow or red osier dogwood so that they may produce many more shoots in the following growing seasons. This behavior helps maintain native plant populations as invasive species become increasingly common.

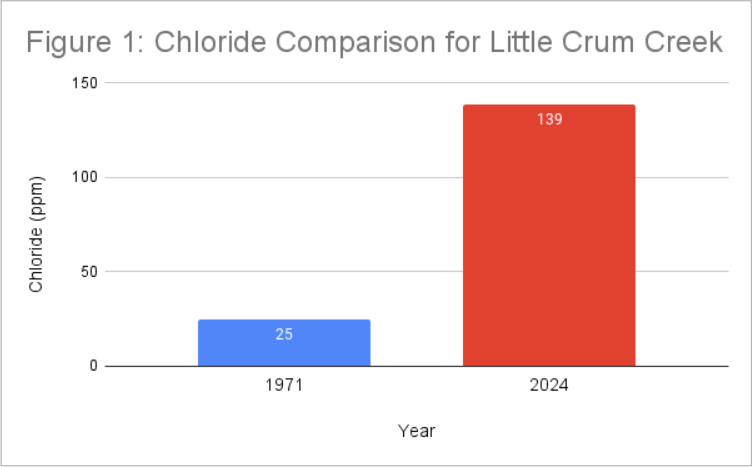

These benefits increase ecosystem biodiversity, organism abundance, and water quality with the impact being so significant that it can be observed by NASA satellites! Green can be seen spreading outward from beaver dams into the surrounding floodplains while other areas without beaver activity wilt under extreme conditions. A study based in Nevada found that in areas where beaver dams had been established, the rate of water evaporation was significantly lower compared to environments lacking beaver activity (Fairfax & Small, 2018). This means that water stays in the ecosystem for longer, and during drought this is critical. Increased water retention supports environmental resilience, with hydrated soils and vegetation being more resistant to wildfires, storms, and erosion, and providing more favorable conditions for wildlife. Depending on the region, increased water level and retention can also allow for the dilution of concentrated salts and nutrients, providing more time for them to be absorbed and broken down, lessening their impact on the environment as a result.

As temperatures continue to rise with each passing year and the weather becomes increasingly unpredictable, these friendly rodents provide fortification and solace for wildlife and humans alike. While they may have a historical reputation as a nuisance, their beneficial environmental impacts are undeniable. Beavers are our allies in the fight to protect and remediate our environment and they sure do look cute doing it!

References:

Dewey, C., Fox, P. M., Bouskill, N. J., Dwivedi, D., Nico, P., & Fendorf, S. (2022). Beaver dams

overshadow climate extremes in controlling riparian hydrology and water quality. Nature

Communications, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-34022-0

Fairfax, E., & Small, E. E. (2018). Using remote sensing to assess the impact of beaver damming

on riparian evapotranspiration in an arid landscape. Ecohydrology, 11(7).

https://doi.org/10.1002/eco.1993

Fairfax, E., & Whittle, A. (2020). Smokey the Beaver: Beaver‐dammed riparian corridors stay

green during wildfire throughout the Western United States. Ecological

Applications, 30(8). https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.2225

Hood, G. A., & Bayley, S. E. (2008). Beaver (Castor canadensis) mitigate the effects of climate

on the area of open water in boreal wetlands in Western Canada. Biological

Conservation, 141(2), 556–567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2007.12.003

Margolis, B. E., Castro, M. S., & Raesly, R. L. (2001). The impact of Beaver Impoundments on

the Water Chemistry of two Appalachian streams. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and

Aquatic Sciences, 58(11), 2271–2283. https://doi.org/10.1139/f01-166

NASA. (n.d.). NASA data helps Beavers build back streams. NASA.

https://spinoff.nasa.gov/Beavers_Build_Back_Streams

Rosell, F., & Campbell-Palmer, R. (2022). Beavers: Ecology, behaviour, conservation, and

Management. Oxford University Press.