By Aaron Coolman, Motus Technical Coordinator and Avian Ecologist

In January, the Bird Conservation Team traveled to West Virgina to join 150 of North America’s most prominent ornithologists. Attendees came from across the U.S., Canada, Mexico, and regions of Central America. Winter’s blessings were clearly in our favor, greeting us in the mountain highlands of West Virginia in a soft, fleece covering of snow. Dark-eyed Juncos scattered the campus in contrasting shades of charcoal and snow-white bellies atop pink legs, and Carolina Chickadees served as tour guides, escorting the hurried scientists between adjacent buildings. We gathered to meet in person for the first time to discuss the Road to Recovery (R2R) movement which focuses on the effort to recover bird species in rapid decline throughout the U.S. and Canada.

R2R was started on the heels of the famous 3 Billion Birds article published in the journal Science. This groundbreaking publication presented the most comprehensive and up-to-date population trend analysis for 529 species of birds known to breed in the U.S. and Canada, and the results were staggering. Since 1970, nearly 3 billion breeding birds have vanished from our continent. Furthermore, 112 species have experienced a global population decline of 50% over the last 50 years and are expected to continue declining over the next 30 years. These birds have been dubbed the “Tipping Point Species”. As a frame of reference, there are approximately 700 bird species that regularly breed in the U.S. and Canada on an annual basis. This report on impacted species wasn’t a gut punch- it was an abdominal rupture.

The R2R team recognized that the current conservation efforts weren’t working, so they called on a new group of talent to enhance their efforts. Social scientists were hired, and quickly new strategies for on-the-ground conservation were implemented. Instead of remaining siloed in echo chambers of technical language and research publications, social scientists emphasized the importance of engaging community members and local stakeholders early in the planning stages of new or existing projects. As a result, the main theme of this movement is that the “human dimension” is critical to success, yet is frequently left out of the equation by scientists. When time is taken to include those who are impacted by conservation initiatives, projects can move towards a common goal of co-production rather than scientists being seen as “luddites” or enemies of societal progress. Preserving a critical wetland hosting native amphibians, reptiles, and fishes; changing a developer’s plans to include wildlife-friendly designs; convincing a forester to leave a selection of mother trees to promote reforestation and early-successional habitat- all of these scenarios and more come to life when scientists extend beyond their labs and into real conversations with key stakeholders.

After the first day of presentations, I quietly said to my coworkers: “Doesn’t WCT already implement many of these practices?” Lisa Kiziuk, Director of Bird Conservation Program, chuckled and replied: “We absolutely do.” And it’s true. We are oftentimes reaching beyond the boundaries of our preserves to meet the community where they are at. The Grassland Bird Collaboration (GBC) is a prime example. For more than a decade, Zoe Warner, GBC Program Manager, has been monitoring breeding birds utilizing the vast hay meadows of Doe Run in southern Chester County and building relationships with the local landowners and farmers. In 2022, WCT officially created the GBC and has since hosted bi-annual meetings in Doe Run to further engage the community responsible for these grasslands. Farmers and landowners, together with conservation partners, have been invited to share their thoughts and experiences with the program which has produced invaluable feedback. This engagement has been crucial to the success of the program, and since its inception ecosystem indicator species such as Bobolink, Eastern Meadowlark, and Grasshopper Sparrow breeding numbers have noticeably increased throughout Doe Run.

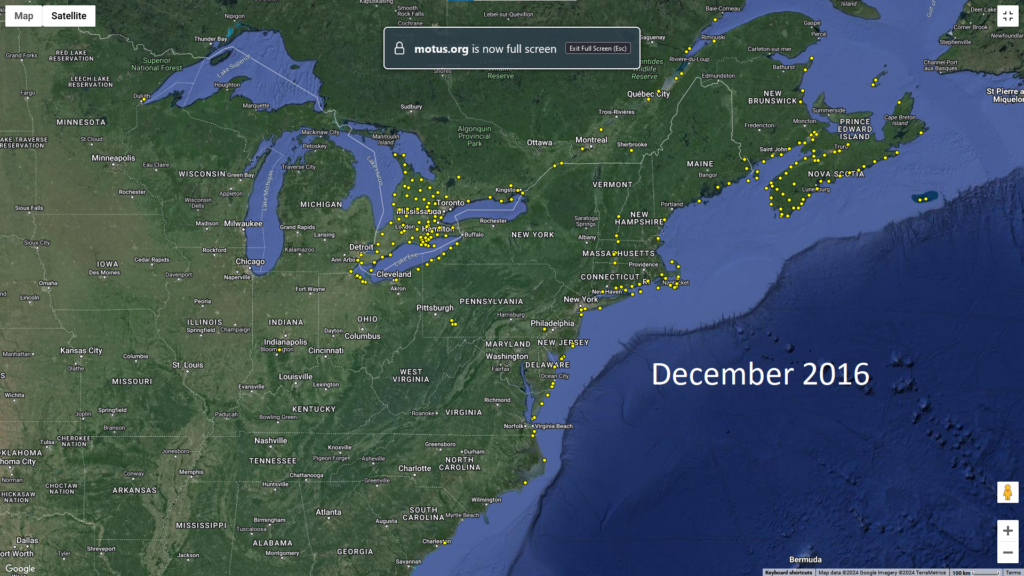

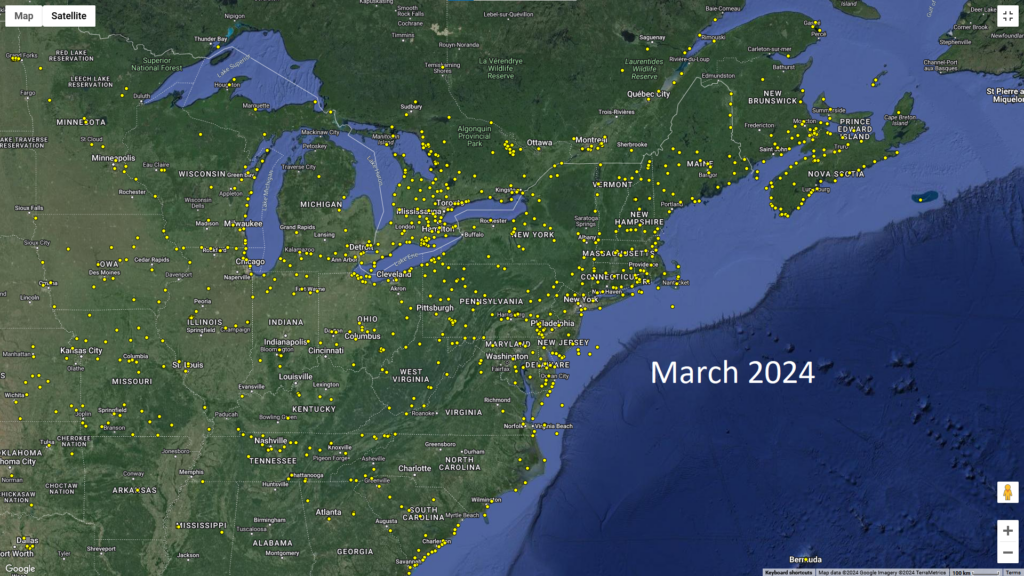

R2R emphasizes that conservation biology requires scientists to work collaboratively. Our efforts are immeasurably stronger when people with diverse skillsets work towards a common goal. These efforts can be focused on single-species recovery, such as the Golden-winged Warbler Working Group or Evening Grosbeak Working Group championed by the R2R movement. Or they can support a hemispheric suite of species, like the Motus Wildlife Tracking System. Motus is a network of Automated Telemetry Receivers that are built and monitored by independent researchers primarily across the Americas, Europe, and Australia. WCT first became involved in this global network in October, 2016, with the first station of many being installed right in our backyard at Rushton Farm. Thanks to our dedicated partnerships with Powdermill Avian Research Center, the Pennsylvania Game Commission, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Maryland Department of Natural Resources, and many others, the Northeast Motus Collaboration has installed, upgraded, and actively monitors over 160 Motus stations.

As the coverage of this network continues to expand, researchers can now study animal migrations at national and international scales. Our own Shelly Eshleman, Motus Avian Research Coordinator, has been using Motus to analyze migration patterns and habitat use of Eastern Towhees, an early successional or “shrubland” habitat specialist whose population is in precipitous decline. Our colleagues from western Pennsylvania are using the network to investigate migration patterns and population declines of Evening Grosbeaks, perhaps the most charismatic of the winter finches. The GBC has spearheaded an effort to study migrations of Bobolinks in Pennsylvania, Vermont, and Maine to compare how different populations migrate using Motus.

The impetus for our involvement in Motus was an idea from Scott Weidensaul and David Brinker, who together with Lisa thought Motus would be an exceptional opportunity to study the migration patterns of Rushton Farm’s favorite owl: the Northern Saw-whet Owl. I am thrilled to announce that in autumn of 2024, I will be bringing our 7-year Motus journey back to the place it started. Through a collaborative effort with Project Owlnet and the University of Delaware, I will be leading a project alongside Scott and David to study the migration patterns of Northern Saw-whet Owls using the Motus network we have worked so hard to build. I am inspired every day to work with as talented a group of dedicated conservationists and scientists as those at WCT and I am delighted to bring this new project to our organization. The Road to Recovery conference in Shepherdstown taught me many things, but the one that stands out is that we can’t accomplish our goals alone, and certainly not without support from a community. The one we have in Willistown is special.