WILLISTOWN, PA (APRIL 20, 2020) — A major grant from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) will enable a research partnership that includes the Willistown Conservation Trust in Chester County, Pennsylvania, along with a number of state agencies and nonprofit organizations, to dramatically expand a revolutionary new migration tracking system across New York and New England.

The grant, totaling $998,000, has been awarded to a partnership led in part by the Northeast Motus Collaboration (northeastmotus.com), which includes the Willistown Conservation Trust; the Ned Smith Center for Nature and Art in Dauphin County; Project Owlnet, a nationwide cooperative research initiative; and the Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Powdermill Nature Reserve in Westmoreland County.

The New Hampshire Fish and Game Department is the lead agency, along with the Pennsylvania Game Commission, Massachusetts Department of Fish and Game, and the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife. Other partners include New Hampshire Audubon, Massachusetts Audubon and Maine Audubon.

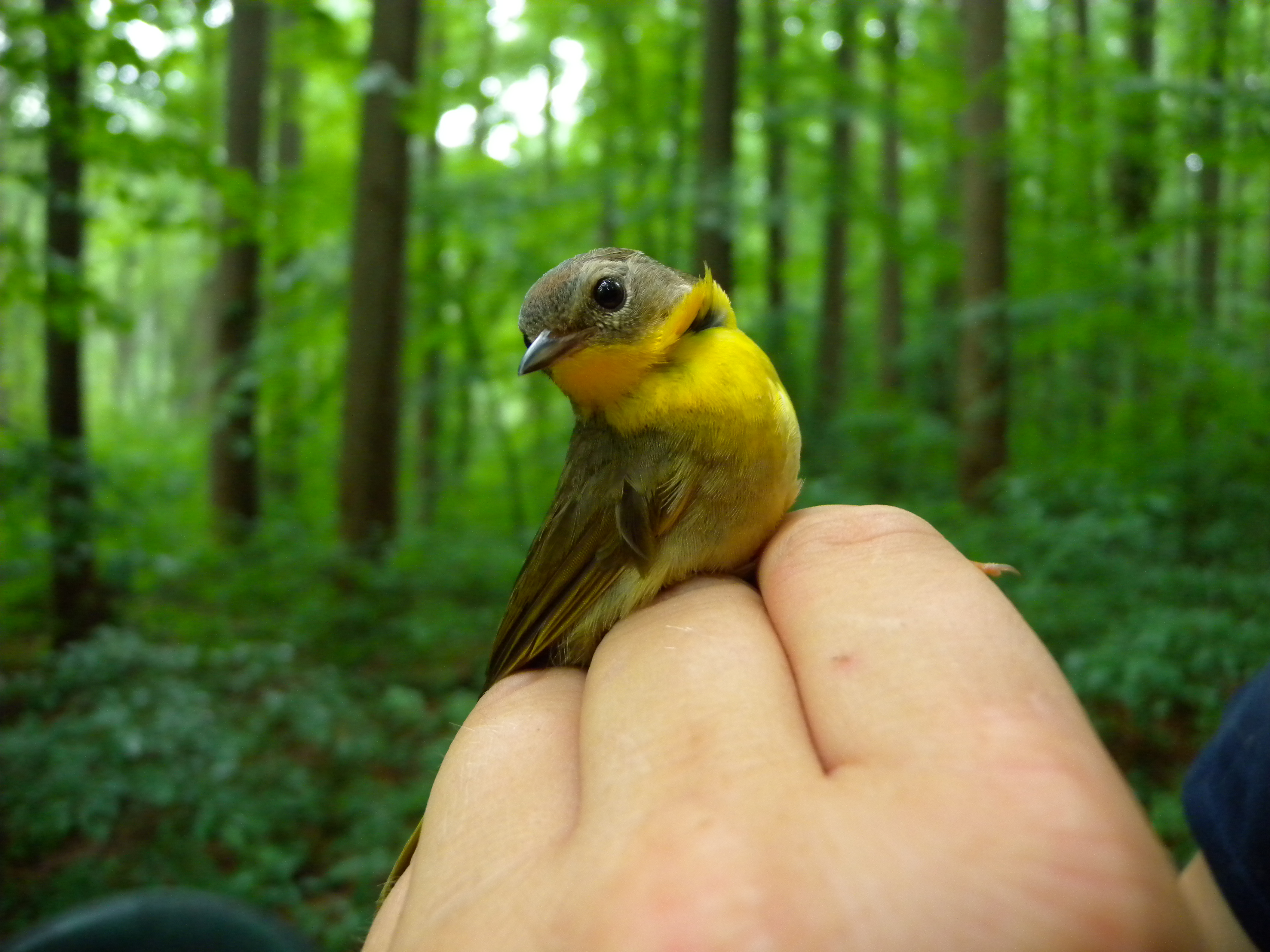

The grant will allow the partners to establish 50 automated telemetry receiver stations in New York, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Vermont, Rhode Island, New Hampshire and Maine. These receivers will track the movements of bird, bats and even large insects tagged with tiny radio transmitters called nanotags — so named because they are tiny enough to be placed on migrating animals as small as monarch butterflies and dragonflies. The receiver array will be part of the rapidly expanding Motus Wildlife Tracking System (motus.org), established in 2013 by Bird Studies Canada, which already includes nearly 900 such stations around the world.

Together, the combination of highly miniaturized transmitters — some weighing just 1/200th of an ounce — and a growing global receiver array allows scientists to track migrants previously too small and delicate to tag with traditional transmitters, like a gray-cheeked thrush that made a remarkable 46-hour, 2,200-mile non-stop flight from Colombia to Ontario.

This is the second major USFWS grant for Motus expansion that the Northeast Motus Collaboration has received. In 2018, the agency awarded the collaboration about $500,000 to build 46 receiver stations in Maryland, Delaware, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and New York. The collaboration had already constructed a 20-receiver array across Pennsylvania in 2017 using private, foundation and state grant funds.

Besides significantly increasing the telemetry infrastructure across the Northeast, this new USFWS grant specifically targets several species of greatest conservation need in New England. Research collaborators will use nanotag transmitters to study the migration routes, timing and behavior of American kestrels, the region’s smallest falcon and a bird that has experienced drastic and largely unexplained declines across New England.

Other scientists will use the smallest nanotags to track the movements of monarch butterflies from the region, which have also suffered large population declines, but about whose migration little is known. The tracking information will help conservation agencies map the best areas to target for land conservation and habitat improvement, like encouraging the planting of milkweed for monarch caterpillars. Finally, researchers will also conduct testing to better understand the detection limits of newly developed versions of this new technology.

While the grant focuses on a few target species, the value of the expanded receiver network has much broader implications. Any nanotagged animal that flies within nine or 10 miles of any of the receivers will be automatically tracked.

“Conservationists are rightly concerned about kestrels and monarch butterflies, and the work funded by this grant that may give us answers that allow us to reverse their declines,” said Lisa Kiziuk, director of bird conservation for the Willistown Conservation Trust. “But by greatly expanding the overall Motus network, the grant will also provide scientists and resource agencies with a treasure-trove of information on dozens of other migratory species, from at-risk songbirds like Bicknell’s thrush and rusty blackbirds to rare bats that travel through the Northeast, and about whose movements we know little or nothing.”

“For me, this project is important because never before have we had the technology to see intimate details of an individual species’ migratory pathway in this way,” said Doug Bechtel, president of New Hampshire Audubon. “Motus technology and this particularly dense array that will be constructed in New England, especially in conjunction with the expansion in the mid-Atlantic states, will enable conservation organizations, industry leaders and legislative decision-makers to see how habitats are being used on a landscape level and make associated conservation decisions based on near real-time data.”

CONTACT INFORMATION

Lisa Kiziuk, Director of Bird Conservation, Willistown Conservation Trust. 610-331-5072, lkr@wctrust.org.

Scott Weidensaul, Northeast Motus Collaboration. 570-294-2335 (cell), scottweidensaul@verizon.net.

Willistown Conservation Trust, located in Chester County PA, is a land trust focused on preserving open space and habitat protection in the Willistown area. The Trust’s Bird Conservation team has operated the Rushton Woods Bird Banding Station since 2007, and has been a lead partner in the Northeast Motus Collaboration to save migrating bird species since its inception in 2016.