The last day of August was the inauguration of our eighth fall banding season at Rushton Woods Preserve. Aside from the hemispheric wave of billions of songbirds south on the heels of the retreating summer, there is another local rhythm of which we banders are lucky to be a part. If an extraterrestrial being were to observe this banding production from above, it might resemble some sort of strange amusement park. In the central meadow, goldfinches ride the tall purple meadow thistle down to the earth like dumbwaiters and then launch off using the rebounding stems like slingshots. As this entertainment goes on, the banders ride the carousel every thirty minutes around the peripheral hedgerows, checking the nets for winged goodies. After getting their wristbands at central ticketing, the birds get ejected back out into the park while eager human visitors stream in through the turnstiles from the farm fields.

Banding reveals what birds are using this unique 86-acre nature preserve, the heart of which is actually a sustainable small-scale farm. Rushton Farm will be celebrating its 10th anniversary this month— 10 years of proving that farms can support both people and surrounding habitat without feeding the stereotype that farming is the most polluting industry on earth. We have seen an increase in the number of bird species over the years using the “green fences” of early successional trees and shrubs that have matured around the farm. There was our first Yellow-breasted Chat banded on September 10th of last fall, a bird that is seldom seen outside of the breeding season due to its skulking habits and preference for dense shrubby thickets.

Last fall we also banded our first Yellow-billed Cuckoo after being taunted by their milky cooing high in the caterpillar-filled canopy of the hedgerows for seven years. Our captive cuckoo was most likely hatched that summer from a nest we found in dense honeysuckle shrubs and was still clinging to its nursery hedgerow on its banding date of October 25th, making it one of the latest Chester County cuckoo records. We said a prayer upon release as we knew he had a long and treacherous nocturnal migration ahead of him to his South American wintering grounds.

In addition to species diversity and abundance, banding gives us finer details of our bird population including individual longevity and site fidelity. For example, during our MAPS (Monitoring Avian Productivity and Suvivorship) banding program this summer, we recaptured a handsome Northern Flicker originally banded by us as a Third Year adult in 2013. That makes him 7 years old now, so he has theoretically been returning to the summer woods of Rushton ever since we first blazed the original net lanes and completed the rigorous habitat survey to become one of the 1200 MAPS stations providing long-term vital rates of North American landbirds to the Institute for Bird Populations.

Banding recaptures also give us valuable insight into local post-fledging movements, a previously understudied part of the avian life cycle that is now gaining more attention from scientists. Our MAPS breeding banding occurs in the open woodland of Rushton where many of our babies are hatched in June and July. At the end of August when we begin fall migration banding back in the shrubby hedgerows bordering the farm, we often recapture some of our woodland youth —a testament to the importance of such early successional shrub habitat. This unkempt habitat is profoundly significant for the survival of young birds because it offers high food density along with lower density of predators as compared to the open woodland. Post-fledging recaptures of this type over the years have included Ovenbirds, Wood Thrush and Veery to name a few.

Another important reason why we band is to understand stopover ecology, or how migratory birds use Rushton to optimize fuel loads. Birds only carry fat during migration, which is assigned a numerical score (0-6) during the banding process. Recaptured birds within the same migration season can give us rates of fat gain, which can tell us something about the quality of our habitat. For example, last fall a Black-and-white Warbler that we banded on September 11th with only trace fat (rated 1) was recaptured at Rushton ten days later with a fat score of 5. “Its flanks, thighs and furculum all with buttery glow,” said Doris McGovern who holds our Master permit from the USGS Bird Banding Lab, allowing us to band birds protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act.

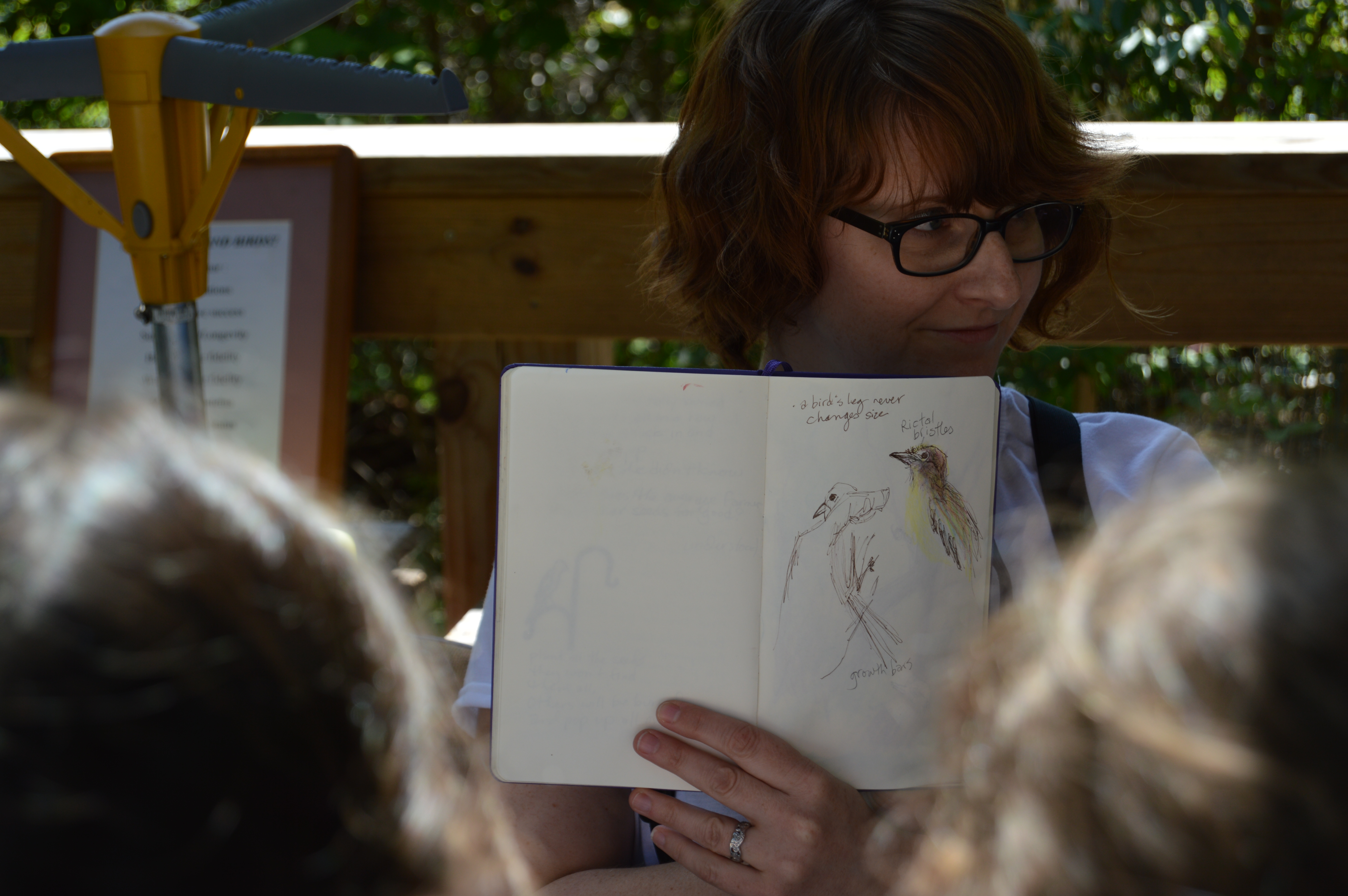

Last but not least, the Rushton Banding Station provides an intimate connection for the people of our community to birds and nature. We invite people under the eaves of our banding station to learn about the importance of birds as the glue that holds the biological web in balance and to understand the global nature of the incredible migration phenomenon that connects all of us beyond country lines. They learn what they can do to help slow the alarming decline in birds. Of course, nothing we preach to them about the wonders of birds and why they should care can compare to what the birds themselves inspire in their hearts after leaving their hands. These pictures show what I mean.

The opening day of this fall (8/31) produced 57 new banded birds of thirteen species including residents, migrants and many young of the year in their very first fall. This is more birds in one day than we had total for the first two weeks of banding last September; the warm weather and unproductive wind patterns of that September made for a slow start to migration. In comparison, the cool weather and north winds of this fall have ensured an explosive start to migration. Notably, our best day last fall once cooler nights became the norm was on October 11th when a record 104 birds were banded!

Even with the slow start, we still closed out last fall season with a grand total of 1,247 birds (100 more than our best fall) in part thanks to the addition of two new nets, which were installed where we noticed high densities of birds. The new nets are working hard for us again this season. One near the compost pile catches goldfinches, warblers and sparrows that are dining in the farm edge, and the other in the middle of the wild meadow catches other migrants that may be traveling to and from our shrub habitat demo area. In all, our 14 nets give us a thorough picture of Rushton’s avifauna.

The showstoppers of our opening day this fall were two Blue-winged Warblers. The first was a stunning After Hatch Year female, and the second was an equally dashing male despite being in his hatching year. Upon closer inspection of our photos, however, we discovered that the male is quite possibly a Brewster’s Warbler (a hybrid of Golden-winged Warbler and Blue-winged). Notice the striking yellow wing bars on our male, which is a Golden-winged trait. Otherwise, he looks like a regular Blue-winged. Golden-winged Warblers have suffered one of the steepest population declines of any songbird species in the past four decades as a result of habitat loss and hybridization. Our probable Brewster’s Warbler may be the closest Rushton ever gets to seeing a Golden-winged Warbler.

Last week, we only banded on Thursday (9/7) thanks to the rain. We kept up our momentum with 46 new birds and 5 recaps, including the usual suspects like Common Yellowthroats and catbirds sticking around from the previous week. Dapper Wood thrushes and Veery continue, while Ovenbirds and Magnolia Warblers were the new arrivals to the fairgrounds. Some notable birds in the hand included a Veery with an overflowing fat of 6 —a true athlete that could have traveled 160 miles that following night at a chilly altitude of 1.2 miles on its way to southern Brazil. An American Goldfinch had a big brood patch (the bare vascularized skin on the stomach used for regulating egg temperature during breeding), indicating that she is a busy mom right now! Begging goldfinch chicks can now be seen and heard in chirping flocks bouncing all over the farm and upper meadows of Rushton , tirelessly harassing their poor parents.

Meanwhile, some of our less ostentatious residents hide in the lower meadow behind the banding station where the morning mist is slow to retreat into the cool shadows of the wood: the iconic Monarch caterpillars. They are a legion this year, with black and yellow stripes to be found on virtually every milkweed plant, despite the fact the plants are past their peak with more brown leaves than green now. These are special caterpillars. They are the fourth generation of this year. This means that once they become butterflies, instead of dying in 2-6 weeks like their brethren they will endure the 3,000 mile migration to Mexico’s fir forests and live 6-8 months to start the cycle again. We wish them luck on their journey and hope that they find enough pesticide-free habitat to sustain them along the way.

Our bird banding station at Rushton Woods Preserve is now open to the public every Tuesday and Thursday morning from 6am until we close the nets at around 10:30 or 11 am. The season ends on November 2nd. Please note the station is closed in the event of rain. For those who cannot make it to the station during the week, we do have this Saturday, September 16th, open to the public for our annual open house (6-10:30 am).

As Doris was wont to say in her daily banding reports, see you in the woods!

Blake