By: Aaron Coolman

Photos courtesy of Brock and Sherri Fenton

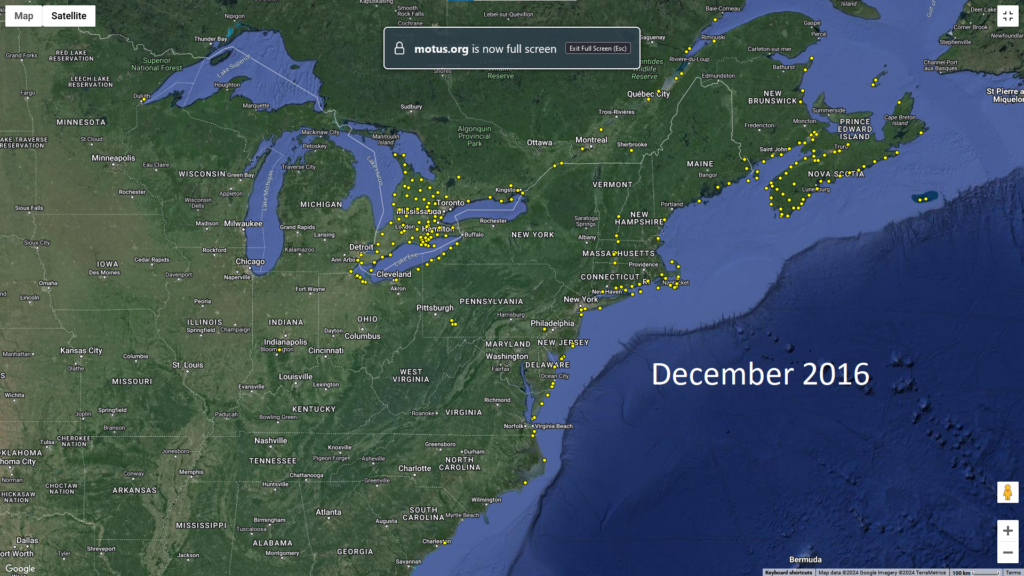

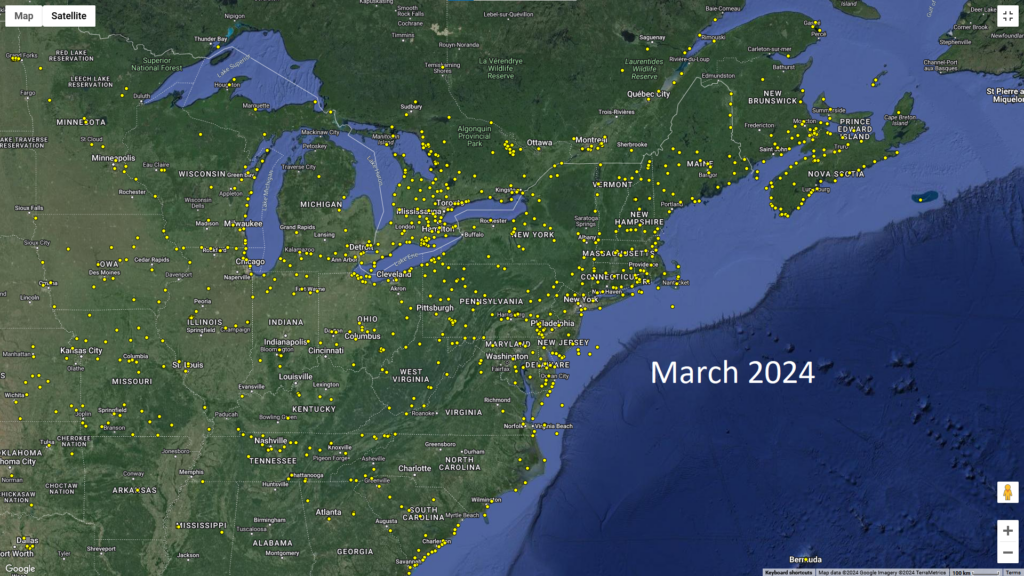

I have spent much time over the last twelve months researching Northern Saw-whet Owls, banding and tracking them around eastern North America. The Northern Saw-whet Owl Migratory Connectivity Project utilizes the Motus network that WCT has worked tirelessly to build and maintain since 2016, deploying Nanotags on saw-whets that will provide tracking data on individuals for nearly two years. My research sent me in pursuit of breeding and migratory hotspots for this secretive species, where I found myself in the remote reaches of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula and Ontario’s boreal forests, to the granite balds and deep fjord river systems of Quebec’s Saguenay region on the north shore of the St. Lawrence River, to coastal and montane banding stations in Maine and Pennsylvania, respectively. Additionally, scientists in West Virginia and Nova Scotia invited me to investigate and track breeding saw-whets at their local study sites.

In all, I drove over 5,000 miles visiting different locations and researchers- the effort has paid off in a big way. The resulting dataset is the largest and most successful telemetry project ever conducted on Northern Saw-whet Owls, and the battery life on all of the Nanotags still have at least 12 more months of power. So far, there have been:

- 124 Nanotag deployments.

- 61 movement detections.

- 5 locations deployed over 10 Nanotags during fall migration.

- 1 location deployed 22 Nanotags during post-breeding dispersal.

- 2 locations deployed 3 Nanotags on actively breeding owls.

- One individual has been detected in the same location for over 100 days and is likely a year-round resident at this location, which has never before been documented.

- 10 owls have flown over 500km during fall migration, some of which have traveled nearly 1,000km.

It was an exhilarating field season, meeting scores of other biologists, scientists, conservationists, and volunteers while having the opportunity to see new landscapes that I had only ever read about or seen photos of. However, the off-season was not long as I have already begun the next (and last) season of fieldwork for this project. Throughout the winter I will be spending my weekends banding and tracking Northern Saw-whet Owls at Powdermill Avian Research Center outside of Pittsburgh, and at Assateague Island National Seashore in Worcester County, MD. For these efforts, I will deploy radio Motus tags that will last nearly two years, and GPS tags that will provide super-precise location data for up to a year.

The primary goal of the project is to determine if Northern Saw-whet Owls utilize the same migration corridors year-to-year, or if they prefer a nomadic approach. Secondary objectives include describing the potential for a residential breeding population of saw-whets in the Central Appalachians of Pennsylvania, in addition to documenting spring migration departure dates. I have created a 2024 Summary providing visual snippets of the results from the project thus far, and a sneak peek into what the plans are for 2025.

**Data published in this blog are current as of 5 February 2025.